We can assume that the builders of Avebury, Silbury Hill, Stonehenge, Glastonbury Tor, to name but a few, were not trying to beautify the landscape.

They were involved in building a network, the use of which is unfathomable, but the monk who wrote the Latin riddle above knew what had certain knowledge of the presence of the Ley network before any of the churches were built.

It is unlikely that a monument such as Stonehenge, even though it is aligned to coincide with known certain celestial events, (this probably being a part of its functionality), has no other function than to act as a calendar or ceremonial temple, as many believe. There are approximately 1000 stone circles upon the British landscape and similar to the Menhirs and monoliths dotted around, these would seem to have a function more than that of a modern day church or cathedral, wherein religious rites and ceremonies are practiced.

It is estimated that around four million man-hours went into the construction of Stonehenge alone, which might seem a disproportionally large investment of a groups resources, when one could simply erect markers to track a heavenly body or watch nature unfold seasonally rather than invest so much to build a calendar. The proponents of the calendar hypothesis seem to have been content with this idea, for the great importance that is attached to those much later pyramid building cultures of South America, the Mayans and the Aztecs, who both designed calendars. Those who advocate that stone circles are for ceremonial purposes, clearly find them synonymous with the sacred cathedrals of a much later age because the cathedrals of the Gothic age were similarly designed according to mathematical harmonies for the population’s spiritual refreshment or wellbeing.

It has recently been discovered by an archaeological investigator, that there was an original Stonehenge called Bluehenge which was constructed with an arrangement of ‘bluestones’, that were later moved to form part of the present Stonehenge circle with its trilithons and Sarsen stones. It is unlikely that ancient man, who had a knowledge ofpi, Fibonacci and Golden mean math, including many other mathematical formulae, would have underutilized his time, on an artwork removing stones from Preseli in Wales, more than 100 miles away, unless they carried out a specific function for him.

Avebury the largest stone circle in Europe lies precisely on the St. Michael Ley Line and also carries out a similar function. The briefest investigation into the construction of Avebury will find that within its seemingly crude rough stoned outline, lies an array of complex geometry that utilized precise surveying techniques.

The Babylonians were the first to become interested in the extent to which planets and their alignments influenced their lives. They constructed star maps so that they might foretell what was to happen to them in the future. This has come down to us in a much misunderstood form, as our modern day horoscope. Those who live in tidal areas are well aware of the power that the moon asserts, and the influence it has on the people that live in those communities. They witness the awesome ebb and flow by an imperceptible force, yet coastal communities arrange their days around the tide. The sun has the greatest influence over our lives and from many of these stone circles where the sun rises or sets there are pertinent features upon the landscape such as hills or dips that coincide with the sun’s cycle and it is thought that if one were to stand at Carn les Boel (the southern extent) the sun would rise on the 8th of May along the St. Michael line, the spring festival of St. Michael. Beltaine is considered a cross-quarter day, marking the midpoint in the Sun's progress between the spring equinox and summer solstice. The astronomical date for this midpoint is closer to 5 May or 7 May, but the St. Michael line is often referred to as the Beltaine line and we shall come to its connection to Bel further on.

Unquestionably most of the stone circles across Britain are aligned astronomically to record the movement of a heavenly body, star group or planet. The stone circles alignments can either be noting the rising or setting of different planets or recording their oscillations and cyclical periods in the heavens. This can be understood in terms of men being able to predict future events and being cognisant of their place in time. The subject of Time and man’s understanding of it seems to be partly the reason that most of the stone circles are astrologically aligned and this subject we will leave until it incorporates with the rest of our enquiry. The fact that Ley lines interconnect these Neolithic sites as witnessed in the St. Michael line and there is a perceptible force that emanates along these lines and at stone circles seems also to connect them by an earth bound energy that these planetary bodies have an influence upon.

The question is… whether modern day man is unaware and yet affected by the unseen influences and alignments around him, much the same as he is unaware of the moon's gravitational pull.

So how should we search for the possible existence of unseen energies within the stone circles and along Ley lines and what influence if any could it have on us? For some, dowsing is the answer, but others don’t regard it as scientific, though an attuned dowser can often find what is there, whereas science has not come up with a way to measure it yet!

This network of standing stones and Ley Line's that interconnect and interweave between, mumps, barrows, tumuli, cairns, dolmens, stone circles and large earthworks, erected from the early to the late Neolithic period, have been placed by early man in such a fashion and design, for a perceived effect they have on him. Maybe we can understand this as affecting what one might call his spiritual nature and possibly this is related to his thought patterns. Certainly, this Monk called Melkin who understood arcane knowledge and who knew of the St. Michael’s Ley line long before it even had that appellation..... leads one to believe that somehow these stone circles connect man to his future. This is in fact alluded to by Melkin in his prophecy.

In the past ancient man’s utility of these circles is evident by their prolific appearance throughout the British Isles and Europe during the Neolithic period. Over the last 5000 years, man's increasing ability to intellectualize rather than work on a more intuitive basis, seems to have rendered the design of less importance, just as our churches today are underutilized. For many it is difficult to intellectualize God but Melkin, not only had an understanding of a Divine plan but also had a definite knowledge of Ley lines and by inference links these lines and circles to future events. Perhaps as many as three quarters of the globe intuitively feel God’s presence and believe in something that they cannot fully comprehend. However, over intellectualization contrarily to man’s intuitive nature can often be witnessed in those ardent non-believers……by the first words that pass their lips in disaster, which shows a conscious denial of what is subconsciously assumed and this across all the cultures, cannot be put down to a mere expression.

Cave paintings in France are artistic evidence that 25,000 years ago Man yearned to understand and portray his place amongst other creatures well before the mini ice age. So what transpired 6000 years ago to cause man’s exponential rise..... (from having thought patterns similar to those of the cave painter), to reach the modern day ability to contemplate abstract potential that has led to the complexities of modern Man’s achievements?

The question that keeps appearing in our enquiry is; apart from painting and sculpture, how was an idea passed on when the earliest form of writing was approximately 5000 years ago? The story of the Bible from Adam and Eve, followed by the flood, through Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, the Prophets and to Jesus, has much to do with this question, as it seems to cover the time span within which we are confining our investigation. The Bible tries at least allegorically, to answer man’s quest for a sense of provenance. Since there are no written records, the Bible attempts to span a void and provide explanation and links a time 6000 years ago to today. The bible relates an account of the interaction by a God through a divine plan which affects man’s potential. How his devises have affected modern man’s potential will be covered in a later chapter.

Figure 1b Showing the three stone circles in Cornwall called ‘The Hurlers’ situated on the Neolithic St. Michael Ley line but this site has no monument to St. Michael.

It is interesting to ponder upon the origins or precursor of what could have been a similar system to what has eventually evolved into our present-day Ley system. Just how old, how big and who conceived of the benefits, that this system would afford a Neolithic population. Approximately 6000 years ago with the eventual flooding of the English Channel.... did part of a much older system that employed tors, hills, prominent rock outcrops and islands gradually get submerged. Has the flooding of Lyonesse caused a repair to be made of what was once a single intertwined entity that may have had connections in continental Europe? As we shall see shortly the St. Michael sites that have usurped the Neolithic sites which were part of this much older system are surely aligned. Is this in some way analogous with the ‘Jerusalem that was builded here’ that Blake alludes to in his nationalistic hymn; built by our ancient forefathers, and yet more recently built upon by persons who understood the benefits of its construction? Are the Satanic mills referred to in the hymn, the manmade earthworks, and mumps positioned with a surveyors precision, upon England's green and pleasant land?

It is one of the objectives of this enquiry to elucidate to the reader the interconnectedness of what is potentially part of a huge ancient functioning system and its relevance in the present era. Who was it in the modern era and which organised body realised that some planned out design is still extant on the British landscape? Did the later designers of the 1300s who built on top of the very locations on which ancient man had built his design, know of its function and have knowledge of its effect upon the inhabitants of Britain?

Figure 2 Showing Glastonbury Tor situated on the St. Michael Ley line, one of many Hill top St. Michael dedicated sites.

Was the mechanism that ancient man tapped into, still functioning when their locations were taken over by modern church builders? The St. Michael churches which are perched on hilltops, in the western part of England, which were part of an older design, seem to confirm that at least in the 1300’s the Neolithic network was perceived to be still functioning.

As in the construction of many of the beautiful Gothic cathedrals that adorn some of the oldest British cities, a long period of time from start to finish for every one of these endeavours was encountered. Unlike the comparative simple construction of a church, the multitude of skills required over a timespan of around 250 years, brought about the establishment of Masonic societies that built these edifices. These societies understood a body of knowledge that was passed down from generation to generation so that these long periods of construction could be accomplished by applying complex rules and designs that, were beyond the capabilities of any individual.

Stonehenge was created in similar circumstances but over a far longer period of time. It has been relocated and refined over a period of 1500 years, before there was any written word. How then did they convey the knowledge of the geometric theorems, acquired astrological records and the details of a preconceived design, from one generation to the next, over such long periods.

There is a vast interwoven set of megalithic sites from Northern Europe all the way up through Scotland and the Orkney’s. Before the flooding of the English Channel, stretching as far as the body of the now submerged land that extended further than the Scilly Isles, it is possible that this network of Ley Line's that is interwoven upon the British landscape, existed and connected through the now flooded plain of a land known as Lyonesse?

So, to carry out the construction of this huge interconnected network, arcane knowledge of the positioning of heavenly bodies, complex mathematics and surveying techniques were surely known. Not only did this information have to be tabulated but correlated and handed down, before any design could be put into construction.

It is safe to assume that the body of knowledge to accomplish all of these tasks would have been secreted amongst the privileged few, but the Masons who built our cathedrals and the Templars who built an array of St. Michael churches upon old Neolithic sacred sites, understood a body of far older knowledge with intended aims, which we will uncover during this enquiry. To bring to fruition and complete such a project, not only did it need the knowledge and purpose as it did in Neolithic times, but in the 1300’s it also needed the wherewithal.

Before we implicate the Templars of having a hand in the construction of a network of churches in southern England..... (supposedly after they had been dispersed and merged into the Hospitallers), suffice it to say that even with modern day democratic governments often the real power lurks discreetly in the shadows. The Templar’s agenda was evolving and taking place undiscovered behind the front of an organisation that appeared as the Knights of Christ and protectors of the holy city.

Saint Michael Ley lines

The Saint Michael Ley line is the line that Melkin the Prophet is saying should be bifurcated at Avebury (within the stone circle SPERULIS). 104 nautical miles at an angle of 13 degrees(SPERULATIS) one will find the Island of Avalon where Joseph of Arimathea is buried. This Island presently known as Burgh Island in Devon was named by Melkin as Avalon and depicted in the Perlesvaus as a tidal Island next to a valley. The confirmation that we have located the resting place of Joseph of Arimathea is found in evidence given by Father William Good who says that 'Joseph is carefully hidden in Montacute'. As one can see, the line Melkin has indicated through his geometrical instructions, (once decoded), goes right through St. Michaels hill Montacute and leads to the Island of Avalon

|

|

The Saint Michael Ley line

A line of neolithic earthworks which has been built upon with a line of churches dedicated to the Archangel Michael. This Michael line in the south of England integrates with other Michaeline churches and chapels which act as 'marker' churches as part of a design that was instigated to locate the Island of Avalon

|

|

St. Michael line- Brent Tor

Brent tor is a St. Michael dedicated church high up on a prominent natural mound not far from the rumb line of churches that make up the Saint Michael line

|

|

Glastonbury tor

St. Michael's tower Glastonbury built with other churches that make up the St. Michael Ley line.

|

|

St. Michael Line -Burrow Mump

A St. Michael dedicated Church alignened with other churches and chapels along the St. Michael ley line.

|

|

St Michael's Roche Rock

Although not on the St. Michael ley line it is similar to other St. Michael prominent sites.

|

|

St. Michael site Carn Brea Redruth

The ite where a Saint Michael Chapel once stood on top of Carn Brea Redruth. This position is precisely upon the St. Michael line of churches running from Chapel Carn Brea through to Avebury.

|

|

Burgh Island- Avalon

The Huers Hut on top of Burgh Island where also Camden bears witness that there was a St. Michael chapel. These Saint. Michael dedicated chapels on Burgh Island and that which was upon Montacute, integrate with the geometry found in Melkin's Prophecy. The two chapels on the Joseph line have disappeared without trace.

|

|

Saint Michael's hill Montacute

The hill upon which was another church dedicated to St. Michael. This is the hill where Joseph of Arimathea was said to be 'carefully hidden'. The hill integrates with the St. Michael line of churches and acts as a marker point in Melkin's geometric puzzle that Locates the genuine island of Avalon.

|

|

Chapel Carn Brea

Another hill top site at the end of the St.Michael line in England which used to have a chapel dedicated to St. Michael built upon it. All that is left on the hill top are the remains of the old tomb.

|

|

The St. Michael line at Redruth

The saint Michal line runs through the site of an old St.Michael chapel on top of Carn Brea near Redruth

|

|

Saint michael's rock to Harnhill St. Michael.

The line running through Glastonbury tor from where the Chapel of St. Michael stood on Burgh Island up to Harnhill St. Michael's church.

|

|

|

|

Figure 4 Showing the Redruth Carn Brea which had a 13th century St. Michael chapel on it, latterly turned into a castle which lies exactly upon the rhumb line of the St. Michael Ley Line.

It might be of interest to note that Drake’s Island in Plymouth was formerly known in 1135 as St Michael’s Island and then subsequently rededicated to St. Nicholas before Drakes heroic defeat of the Armada. This is only noted now as the river Tamar flows into Plymouth and this comes into our enquiry in connection with Tamar, Judah’s twice daughter in law.... yet who bore him twins Perez and Zerah. These events are discussed as the original reason for the arrival of the Zerah line of Jews in the South west.

St. Michael's Mount in Cornwall, made famous because of its rumoured links with the island of Ictis and thus its links to Joseph of Arimathea the tin merchant... stands in Mounts Bay opposite Marazion in Cornwall. To the west of it, not far from Sennen, stands, a Neolithic hilltop site called Chapel Carn Brea upon which, there once stood a small chapel dedicated to St. Michael. Alms, in the past would be given by seamen to the hermits who lived there, so that a fire could be lit and be seen by approaching ships. The chapel was eventually demolished in 1816, after having been allowed to crumble into obscurity through the centuries. Considerable early Neolithic labour to create a mound, which incorporates complex barrows and stone lined cists, has been archeologically excavated 657 feet above sea level on its summit.

The great labour intensive efforts of these people to bury their leaders, although less skilful, seems to correlate with the goal of the pyramid builders of Egypt in the same era. Carn Brea is often referred to as the first and last Hill in England but sixty one nautical miles away lies a small island at this present-day known as Burgh Island, next to a small seaside village called Bigbury on Sea in Devon. This tranquil Island stands as a sentinel, while the tides have ebbed and flowed around it for centuries. This once also had a chapel on it dedicated to St. Michael, which has left no trace of its presence through the passage of time and is rumoured to have once been the site of a small monastery.

Since our enquiry involves Neolithic sites, Ley Lines and St. Michael churches let us try to interlink these facets of our enquiry.

If we extend a line from the base of Chapel Carn Brea where a St. Michael Chapel once stood, passing by a Megalithic stone called the Blind Fiddler, through St. Michael’s Mount and then pass it by Burgh Island, it would pass out into what used to be the lowland plain region that was part of Lyonesse (now submerged), into the English Channel. If we were to keep extending our potential Ley Line onwards into the Pas-de- Calais region of France, one arrives at the small town of Roquetoire, another town famed for its St. Michael connections.

The church that stands today in Roquetoire was built in 1868 and is built in the Gothic style but it replaces a much older church that was built in 1315AD and from its origin was dedicated to St Michael. It had a prominent bell tower and could be seen from miles around. St. Michael the Archangel is said by the villagers to have visited the village in person in a period of severe drought and blessed the inhabitants with running spring water. ‘St. Michael's Spring’ as it is known, is said to have never ceased flowing up to the present time.

Before embarking on the geographical design noted within the pages of this book, the reader should be aware that, any distances are quoted hereafter in nautical miles. This unit as most sailors would know correlates with degrees of Arc, both in longitude and latitude. The ancients responsible for the alignment of Ley Lines, were quite aware of this measurement long before the time of Pytheas the Greek explorer, as exemplified in the relative siting’s of Avebury and The Great Pyramid of Cheops. Using this system defines the 360° taken to circumnavigate the globe from one point of longitude to its return at any latitude. One mile equals one second of 1° so each degree is subdivided into seconds, 60 seconds fulfilling 1°. Meridians however, are imaginary longitudinal lines that go to each of the poles for every Arc of rotation through the 360°.

The St. Michael dedicated sites that comprise what we shall call the Lyonesse line seem to have the same validity as the St. Michael Ley Line, if one takes into account the flooding of the channel. There is a possibility that it was marked out within the same system or network of the original Neolithic sites now submerged. The length of this Ley Line, is found to be 308.5 nautical miles, similar to the St. Michael line which was 316.65.

Figure 5 Showing the Lyonesse line from Chapel Carn Brea through St.Michael’s Mount then through Burgh Island to Roquetoire in France.

Most of this proposed Ley Line runs along the sea floor, so coupled with the possibility that it might be linked in with an older system of Leys, let us investigate what alignments there might be in relation to it, from the British landscape and specifically, from the already discovered St. Michael Ley Line that runs from Carn les Boel through Avebury, northwards to the East Anglian coast. In any search for alignments it is always best to look at Avebury, the biggest stone circle in Europe, while remembering sites like Stonehenge and Old Sarum are of equal antiquity.

Exactly halfway along this newly found Lyonesse line, if a line was scribed at right angles to the Lyonesse Ley Line; it forms a tangent to the Avebury circle and Silbury Hill, just south of it. The north-south line also passed in between and tangential to Stonehenge and Bluehenge, passing within a field's breadth of each site. It was evident after finding that it became tangential also to Old Sarum, that it too seemed to be held on course by these nodal points, like a strand of wicker, the Ley Line conceptually appearing to be constrained in place, as if the nodal points on the land were extended upwards as vertical strands in wickerwork. The skeptic will already be wary with any kind of integration between the culture that constructed Ley's and the later cuture that built churches dedicated to St.Michael. I am just pointing these relationships out so that the reader can either dismiss them or see how hard it is not to see a relationship. By the end of the book the reader can judge whether a line which is defined by an ancient monk named Melkin and also confirmed by a Jesuit priest named Father Good 1527–1586 is the same line we are sent to find by way of a set of instructions given in Melkin's prophecy.

After considering this alignment, a logical progression is to extend the line further up into the North of England, while remembering a piece of information from Melkin, where he speaks of ‘circles of portentous prophecy’ in the same prophecy in which he tells of a bifurcated line, an angle and a meridian that locates a tomb. Melkin, who we shall discuss in detail shortly, wrote his prophecy concerning the Isle of Avalon and Joseph of Arimathea who supposedly brought the Grail to Britain. It would seem that Melkin is divulging information which is hinting at a location where Joseph of Arimathea might be buried andtherefore, should we be looking for clues on a map. Yet in this same prophecy, Melkin uses the Latin word ‘oratori’, literally meaning a religious hymn or chapel but the same word could be construed as a choir, and so informed, we should embark on the next part of our investigation which somw may account as irrelevant but this is how the connections are made that uncover the Tomb site of Joseph of Arimathaea in Avalon

Figure 6 Showing the Ley line which runs north at 90° from the Lyonesse line, tangential to Old Sarum, Stonehenge, Silbury hill and Avebury.

Chapter 3

Geometric forms constructed from the ‘Perpetual Choirs’.

We will discuss the relevance of the Perpetual Choirs in this chapter in relationship to Melkin's reference to a 'Circle of portentious Prophecy' as translated by most commentators. Again the skeptic can either dismiss its relevance to the construction of a Pyramid on the British or include it as relevant. The main point being the line which we have been sent to find by Melkin's instructions which points out the Island of Avalon and the burial site of Joseph of Arimathea..... can be found entirely independantly from any reference to Perpetual Choirs. This Chapter which defines the Pyramid construction is only relevant when we understand the nature of the Grail in a later chapter and its association with the Jerusalem Temple and its relation to the pyramidal form in references such as 'the head of the corner stone'.

Old Sarum has been named as one of the “Perpetual Choirs” noted in the Welsh bardic tradition of triads or “Triade” where three line verse is employed. TheWelsh Triads of the Island of Britain are a group of related medieval manuscripts which contain Welshfolklore, mythology and sometimes corroborated historical fact in groups of three. The triad is a form of stanza, in which objects or subjects are grouped together in three’s, usually with a heading indicating the point of the stanza, followed by verse relating what the subjects have in common. The Triads relate much of British history and often put the escapades of King Arthur into a Welsh arena. Much of the material is in common with that of Geoffrey of Monmouth and Grail stories but tends to confer on King Arthur, a Welsh or heritage.

There is an English translation of the Welsh text from the 1796 edition of a book entitled Fabliex, which in translation means tales, legends or fables, in which the Triads give the names of places for three “Perpetual Choir” locations. These “Perpetual choirs” seemed to have been instigated by the monastic movements, to give praise to God continually day and night in three named locations but may convey a tradition that was instigated at a much earlier date, but which was possibly suppressed by the Roman invaders.

In 1801, Iolo Morganwg wrote that 'in each of these choirs there were 2,400 saints; that is there were a hundred for every hour of the day and the night in rotation, perpetuating the praise and service of God without rest or intermission.'

The three Perpetual Choirs of Britain, given in the translation are the 'Isle of Avalon' (Glastonbury), 'Caer Caradoc' (Old Sarum) and ‘Bangor Is-y-Coed’.

Figure 6a Showing the large oval earthworks mound of Old Sarum with evidence of human habitation since 3000 BC.

Like so many unravelled half-truths, there has been considerable dispute over whether Bangor Is-y-Coed is one of the main sites or whether a fourth contender, Llantwit Major in South Wales, stands as a true candidate. The reason why we should consider such a question only becomes relevant to our investigation in terms of Melkin’s prophecy which purports to give the location of Joseph of Arimathea’s tomb in the form of a riddle in which it is suggested that ‘circles of portentious prophecy’ in connection with a ‘choir’ somehow, geometrically express the whereabouts of his resting place.

In the Old Welsh language, Llantwit Major was known as Llanilltud Fawr and the date of the first settlements in this area are vague. There is a strong tradition that metal merchants from just eleven miles distant across the Bristol channel, exported lead from the Mendip Hills and there is an age old proverb in parts of the Mendips ‘As sure as Our Lord was at Priddy’; concurring with a Cornish tradition of Jesus accompanying Joseph of Arimathea on his trips to Britain as a metal merchant.

Archaeological evidence found in Llantwit Major shows occupation dating as far back as the Neolithic Period and into the Roman era. It is quite possible that it was once an export point for copper ingots from the Great Orm mine further North in Wales. It is only a short distance across the Bristol Channel, from where the lead was exported; it would save foreign traders having to navigate the hazards of the treacherous Welsh coast to the north and may be the reason for the Joseph tradition that exists there.

In Welsh records, the Welsh Triads and the Llandaff Charters, there are references to Llantwit Major being the arrival point of Joseph of Arimathea and his disciples in 37 AD. Local legend in Llantwit Major tells us that Joseph built the first Christian church in the world there, where the first Welsh college, Caer Eurgaine, was constructed.Today there are no signs of the monastic buildings that would have housed these 2400 monks who were rumoured to be part of this college. The Old Church, as the church is now known, is supposedly built on the foundations of earlier buildings. Local lore has it that the old monastic college lies to the north of the present town but no one can be sure of its precise location. Local folklore records that the college was extremely large with over 2000 pupils and it was St. Illtyd who instigated the church, the monastery and four hundred houses for the college in which the pupils resided but as with the other Perpetual Choir site, Bangor Is-y-Coed, there is little evidence of such a large community.

Llantwit Major has always had an association by tradition with Joseph of Arimathea and Joseph’s appellation in the Welsh tongue was ‘Ilid’ which translates into Welsh from the word Israelite and subsequently St. Ilid by the later church. It is highly probable that St. Illtyd in the 5th Century was somehow confused by earlier references to Joseph of Arimathea, thus confusing legend with recorded history. It also seems likely that, through this long-standing and eminent association with Joseph of Arimathea, Llantwit Major was elevated by some to be ranked as one of the Perpetual Choirs in some of the later Triad versions.

It is possible that Joseph landed here but monasteries in this era required close association with saints to encourage pilgrims and it is more probable however, that St Ilid is confused with St.Illtyd, with a following tradition that placed Joseph in Llantwit Major. It seems that an early 18th century mention of Llanwit Major interpolated into the main Peniarth Triad source was the cause of this confusion thus conferring on Llantwit Major the same standing as Glastonbury in its associations with Joseph of Arimathea. The four of these potential Perpetual Choir sites, were supposedly large medieval monastic sites but neither Bangor nor Llantwit Major leave a scrap of evidence behind them, so it is necessary to keep an open mind and to see what can be uncovered.

William Mann writes books about the Knights Templar and there is a recent tale, in one of these, of a ring owned by his great-uncle. When he was a boy, he was shown a Masonic ring by this uncle who was a Grand Master of the Knights Templar in Canada. This ring held a secret chamber and a symbol of two intertwined circles centred on a line that ran through an amethyst jewel. It is with these two overlapping circles in mind centred on a line, that we should further our geometrical design already plotted on the British landscape. References made to squares and triangles marked out in lead on the original floor of Glastonbury’s church before it was burnt down also indicate that there is somewhere to be found a mystery based upon geometric shapes and seems, from varying sources to indicate a quest. In addition to “the circles of portentous prophecy” suggested by Melkin’s prophecy, it would seem obvious having found two new Ley Lines, that we should try to find out what it is that connects all this information together.

Let us commence by finding a point on the Ley line that had been discovered going just East of North out of Avebury. Bearing in mind Perpetual Choir locations and finding the point on our line in a built-up area called Marlbrook; from this point draw a circle that has a radius that passes through all the previous Perpetual Choir sites mentioned except Bangor Is-y-Coed, so that our circumference now passes through Old Sarum, Glastonbury, and Llantwit Major as indicated in figure 7.

Figure 7 Showing the radius connecting the Perpetual Choirs with that of Whitelow Cairn.

One can see that, at the top of the circle that has been scribed, at the point where it intersects the northern extent of the line and subtends the circumference, these lines cross through a point where there is an old Neolithic cairn, just East of Ramsbottom in the North of England, called Whitelow cairn. The reader must remember here that we are trying to assimilate various sources of information, such as the circles centred on a line of Templar origin, clues from Melkin’s prophecy about a choir with allusions to circles of portentous prophecy. Since Whitelow cairn fits neatly onto our Neolithic canvas and defines a point, we should also keep in mind the triangles seen on the floor at Glastonbury that William of Malmesbury declares might hold some mystery.

As we continue on to see where this quest might lead us, let us next scribe a line back to the point of departure of the St. Michael ley line at Carn Les Boel in Cornwall. Straightaway the shape stands out as half pyramidal, so let us replicate this procedure on the other side by extending a line down to the church of St. Michael Roquetoire thus forming a pyramid; covering an area of 29,642 miles with base angles of 51.25° similar to the Great pyramid of Cheops, which has base angles of 51.85°.

Figure 8 Showing the Pyramid form on the British landscape.

One of the first things to notice, following on from the construction process of our pyramidal shape, while remembering the arc that by passed through all the Perpetual Choirs’ sites, is the fact that now the left-handed side of the constructed pyramid passes one mile from Bangor Is-y-Coed (Iscoed), our fourth contender for what can only be a three horse race, as we are referring to a Triad.

The function of the choirs was to maintain the enchantment and peace of Britain, but one must ask, is it just by coincidence that Bangor had been named as a Perpetual Choir site in earlier translations? It has been suggested that Llantwit Major was substituted for Bangor in a triad translation from the Welsh by Iolo Morganwg much later and who lived near and promoted Llantwit Major. The 1885 O.S map of Glamorganshire shows approximately 2 miles north of Llantwit Major, a location called Nash Manor which has inscribed on the map next to it,“Monastery,remains of” also shown on an earlier O.S map from 1813,so this could well have been the site Iolo promoted.

A monastery had been built at Bangor Is-y-Coed by St Dunawd and had been destroyed in 616AD along with most of its occupants in the battle of Chester. The Venerable Bede relates that 1200 monks were killed even before the battle took place. "Most of these priests came from the monastery at Bangor where there are said to have been so many monks that although it was divided into seven sections, each under its own abbot, none of these sections contained less than three hundred monks, all of whom supported themselves by manual work. About twelve hundred monks perished in this battle and only fifty escaped by flight."

In the oldest version of the Triad mentioned, Thos. Wiliems, ‘Trefriw’, only spells ‘Bangawr’, the same as Robert Vaughan’s version ‘Peniarth’, as ‘Mangor’. In the John Jones version which came out at the same time as Vaughan’s he writes ‘Bangawr vawr yn fford y Maelawr’; the ford indicating a place where one crosses a river, so we can assume that it is Bangor on Dee they are all referring to and the ‘Bangawr’ or ‘Mangor’ is just a shortened version of an exceptionally long descriptive place name. The modern day Bangor Is-y-Coed, meaning Bangor on Dee, ‘Bangawr’ originally indicating a monastery; could conceivably be confused with the Bangor near Anglesey where another murderous act took place in Roman times. Before the battle took place in the year 613 AD according to Bede, or in 6O7 AD, dated in the Saxon Chronicle it relates;

“the most brave Aedilfrid, king of the Engles (then pagans), a great army being collected, gave, at the city of Legions (which was called by the Engles, Legacaestir) by the Britons, however, more rightly Carlegion (now called Chester), a very great slaughter of that perfidious people: and when, the battle being about to be done, he saw their priests, who had assembled to pray God for the soldier managing the battle, he enquired who these were, and what they had assembled in that place about to do. Now a great many of them were from the monastery of Bangor, in which so great a number of monks is reported to have been, that when the monastery was divided into seven parts, with the rulers set over them, no portion of these had less than three hundred men, who all were accustomed to live by the labour of their own hands. On account of the battle, a three-days-fast being accomplished, had assembled with others, for the sake of praying, having a defender named Brocmail, who could protect them with their prayers, from the swords of the barbarians. When king Aedilfrid heard of their coming, he said: “If, therefore, they cry to their God against us, and certainly, they themselves, although they do not bear arms, fight against us, who are persecuted by their imprecations adverse to us”: he therefore ordered in that abominable militia, not without great loss of his own army. They report, about two thousand men of those who had come to pray, to have been extinct in that battle, and only fifty to be fallen in flight; Brocmail, turning with his soldiers, their backs, at the first coming of the enemy, left those whom he ought to have de-fended, unarmed, and exposed to the smiting sword”.

In the edition of the translation of Fabliaux by George Ellis, it specifically names in a four line text originally from the Welsh, that the Perpetual Choirs in Britain are; The Isle of Avalon(Glastonbury), Old Sarum( Caer Caradoc) and Bangor Is-y- Coed(Mangor Iscoed) but as we shall discover shortly, the Island of Avalon and Glastonbury have little to do with each other.

Two early chroniclers, William of Malmesbury and Geoffrey of Monmouth in their respective writings do not make this connection between Avalon and Glastonbury being one and the same place. As we shall uncover shortly, Glastonbury invented itself as the Isle of Avalon, insisting that the Somerset marshes were sodden in the sixth century when Arthur died, thus rendering Glastonbury into an Island at the appropriate time. At this stage, suffice it to say, no one should dispute Glastonbury’s pre-eminence in having had the first Christian church established there by Joseph of Arimathea. None the less, the monks are indisputably culpable of distorting the truth and guilty of polemicism by trying to re-establish a link to Joseph that is not evidenced except by forgery. Both Joseph of Arimathea through Melkin and King Arthur through Geoffrey of Monmouth were said to be buried in the Isle of Avalon and up to the present day the Isle of Avalon remains synonymous with Glastonbury. This association seems to have sprung from the monks of Glastonbury having fabricated evidence of King Arthur’s tomb being found there.

On investigation, we find that the modern town of Bangor on Dee is on a floodplain and the River Dee has changed its course, several times in the intervening years since the destruction of the monastery in 616 AD. There is an explanation as to why there is no trace of what was supposedly a huge monastery with at least 2400 monks in residence and this is revealed in the river Dee’s change of course across its flood plain. Recent archaeological evidence shows that in 600 AD the monastery would have been situated within 0.2 of a mile of the line extending down from Whitelow cairn to Carn Brea on our pyramidal shape formed on the landscape. It seems then, evidenced in our geometrical construct so far, that the four Perpetual Choir sites act as indicators on a map. It seems an odd coincidence, not unlike some St. Michael churches, that the monastery that existed in Llantwit Major has vanished without trace, with no-one being sure of its original location and no river Dee to blame for having washed it away; yet local Llantwit Major records show, that there was a Benedictine monastery until the dissolution. The association of the Perpetual Choirs to the rest of our investigation may seem tentative or insignificant but the apex of this Pyramid was defined by the radius running through three of the Choir sites and will lead us to the discovery of the Holy Grail’s whereabouts further in our enquiry. However If we had not followed through these steps to find the pyramid dimension another circle, the center of which is defined by two Ley Lines would lead us to the same design.

Chapter 4

The connection between Avalon and the fabled Island of Ictis.

Leaving our geometrical construct for the moment, it is necessary to concentrate our enquiry on another location of which there is no trace in the modern world. The reason for trying to accurately locate the island of Ictis is because we know that it was engaged in the tin trade. If we can establish Ictis as a definitive location today, then we will see how this Island confirms the directions given in Melkin’s prophecy. We know that sometime after the first Roman invasion of Britain that Joseph of Arimathea was a tin merchant as the Cornish traditions have maintained.

Researchers over the last 2000 years have tried to find the location of the fabled ‘Island of Ictis’. The strange coincidence of geometrical directions being given in Melkin's prophecy establish the location of Burgh Island in Devon as the Island of Avalon but they also say that Joseph of Arimathea is buried on the Island. Now it would be a coincidence if Ictis an Island where tin was teaded from can be established as being the one where the most famed tin merchant was buried.

There has been much written and incredible ingenuity used by scholars and commentators alike, to fit facts as they see them, to agree with their own preference for the location of Ictis.

It would appear that for all this effort in the modern era, no one has definitively managed to locate it. The references about Ictis came from many different sources, Greek and Roman over a period of approximately 400 years, but recent commentators have not been able to see the pertinent facts that were related, in perspective.

ICTIS ISLAND, ALSO KNOWN AS AVALON

ICTIS ISLAND, ALSO KNOWN AS AVALON

This search for the Island of Ictis originated due to a Greek named Pytheas, who made a journey by sea, circa 325 BC and wrote a Chronicle of his voyage, which no longer exists. He mentioned the island in his journals and left quite specific references to it, the most pertinent being that it dried out at low tide and was located in Southern England; hence its permanent association with St. Michael’s Mount, just south of Marazion in Cornwall. It is because of Pytheas’s notoriety and the fact that his original writings no longer exist, that over time, references from other ancient chroniclers that mention his journey and his description of the island and its environs have become garbled.... some of the chroniclers simply disbelieving much that he related.

Courtesy of James and Jade

Figure 9 Showing St Michael’s Mount, Marazion, and the rocky foreshore, on which the foreign trading vessels were supposed to land at all states of the tide.

Pytheas was an astronomer and a geographer, who may have been the first Greek to visit and write about the Atlantic coast of Europe and the British Isles. The Latin word Britannia is derived from a word first reported in ancient Greek by Pytheas of Massalia. It is a shame that his main work, which was called ‘On the Ocean’ is no longer extant, but we know something of his travels through the other Greek historian called Polybius, who lived around 200 BC. Timaeus even mentions Ictis before Polybius while other ancient writers who mention Pytheas’ voyage are Posidonius, Diodorus Siculus and Strabo, who all wrote before the birth of Jesus.

Strabo relates that Dicaearchus who died about 285BC did not trust the stories of Pytheas but we shall see his mistrust was not fair.

Diodorus, who gives a good description of the island and its trade, (much of which can be ascertained to be from Pytheas’ original eye witness description) also tells how large cart loads of tin were brought across a tidal causeway to the island. Diodorus is also seen to be quoting from Posidonius, while Pliny on the subject of Ictis, who wrote circa 50 AD is also quoting from Timaeus (contemporaneous with Pytheas) but not directly from Pytheas.

It is evident that over the period of four hundred years when these Greek and Roman historians were recounting Pytheas’ exploits, mostly second or third hand, an inaccurate account has been passed down about an island that traded tin with a name called ‘Ictis’ that existed in southern Britain. The effect has been like that of Chinese whispers around a single dinner table without the added difficulty of translating Greek into Latin and we can witness how different the message from the first to the last may be distorted.

Pytheas’s voyage seems to have been intended partly as a commercial venture looking for opportunities in trade with his own city Marseille and the other part scientific. Pytheas was long before Galileo in attempting to assert that the earth was round and this proof was known by the ancient world. This proof could only be arrived at by taking sightings of the sun at different latitudes and as Pytheas proceeded North, he observed the change in the length of daylight and he observes “the midnight sun,” confirming he went far up to what he called Thule, which presumably is confirmed by later chroniclers as Iceland.

There is mention of a passage that he made, said to be six days long and this could be one going north to Scotland but many commentators think that he only went up the eastern side of Britain (but this would deny his having described the shape of Britain as triangular). The lost interpretation of the six days could even be an account of the journey to reach southern England from Marseille. Some ancient writers seem to give it as a quote from the ‘Britains’ about the distance to travel to Ictis to procure tin. The ‘six days inwards’ (introrsus) related byTimæus, and quoted by Pliny, says, that this Mictisor Ictis, “was six days sail inwards from Britain” and given as a direction supposedly by the Britons to Pytheas on his arrival in Belerion. This confusion has led most Ictis investigators astray and was obviously related out of context, as much of the other information has been.

Pliny’s quotation of Timaeus ’six days sail inland from Britain, there is an island called Mictis in which white lead is found, and to this island the Britons come in boats of Osier covered with sewn hides’ could be a confusion of the six days in which it would take to get from Lands’ end to northern Scotland averaging 70-90 miles a day if indeed Pytheas went up the western side of Britain with no mention of Ireland.

Diodorus’ quotation of Posidonius who travelled in Britain around 80BC describes the metal workers of Belerion carrying their tin to a certain Island called Ictis which acted as a great trading post for merchants. This quote coupled with the fact that the Isle of Wight's Latin name ‘Vectis’ being similar to ‘Ictis’, has also led to more confusion as much trade was known to take place from this area. Some commentators have assumed the 'Six days Inwards' can be applied to the journey along the Southern coast from where Pytheas initially made contact with the inhabitants of the Southern tip of Belerion, all the way to Thanet in Kent, another possible candidate for Ictis, as Kent is mentioned in his Journal.

Pytheas probably did not explore much of the mainland of Thule. but gives an account of sea ice. We do not know from Thule where he bore southward for the return voyage, but again this could be another confusion by later cronichlers as they sailed south for six days and nights before they reached the shores of Britain.

We hear little from subsequent commentators about Pytheas’s return along the eastern shore of Britain as far as Kent, but his expedition returned successfully by the Channel and the Bay of Biscay, back to the mouth of the Gironde if indeed this is where he had started from.

Pytheas as a ships navigator had mastered the use of the "Gnomon," an instrument similar to the hexante or Sextant as it is known today. This instrument was used by Phoenician and Greek navigators since very early times and Pytheas used it to calculate the latitude of Massalia, which he found to be 43' 11' N, almost matching the exact figure of 43' 18'N for where Marseilles lies today. It seem likely that it was a committee of merchants from Marseilles that engaged the services of Pytheas to undergoe his voyage of discovery. He was a renowned mathematician of that city, who was already famous for his measurement of the declination of the ecliptic, and for the calculation of the latitude of that city, by a method which he had recently made known of comparing the height of the gnomon or pillar with the length of the solstitial shadow. Many of the ancient writers disbelieved Pytheas’ account of his journey and the distances involved and much interpolation, interpretation and rationalisation of subsequent writers has meant that we are now no longer sure of which parts relating to Ictis have been related accurately.

It is 238 miles from the mouth of the Gironde to Ushant, a leg of the trip that Pytheas records “as three days away” by Strabo then one days sail to the Belerion coast. Pytheas was averaging 79.3 miles a day. The four days, quoted by Diodorus from the Gironde is indicating he had a quick passage from Ushant, probably sighting the Lizard first only 89 miles away. It was hereabouts at an undisclosed landfall, he made his enquiries to the ‘Britons’ about tin. Pytheas was probably told it was two days further up channel, but Timaeus records that the Britons, said the Tin would be available six days inwards in an island which they went to in wicker framed boats covered with hide, (these wicker boats probably only used locally). It is only fifty five miles from the Lizard to Ictis and if Pytheas did record that the journey in total was six days, Pytheas most probably sailed along the coast for the last two days stopping overnight so that he did not miss the island.

Timaeus recorded Pytheas in Greek, then it was rendered by Pliny the Elder in Latin, influenced by other previous references that were possibly interpolated nearly 300 years later. This stands little chance of being an accurate record with the original detail given by Pytheas. It seems most likely that, Pytheas’s intention was to give a meaningful reference of six days in total to the Island of Ictis from the Gironde, detailing “inwards” up channel from his present location. This seems to be the obvious solution, but this six day period may indeed be in reference to another part of his trip and the context has been muddled. One can tell that Diodorus is not giving a first-hand account but the ‘we are told’ reference from this next extracted account is most probably referencing details given by Pytheas: Britain is triangular in shape, similar to Sicily, but its sides are not equal. This island stretches obliquely along the coast of Europe, to a point where it is least distant from the mainland, we are told, is the promontory which men call Cantium,(Kent) and this is around one hundred stades from the land, at the place where the sea has its outlet,(The Dover Straits) whereas the second promontory, known as Belerium, is said to be a voyage of four days from the mainland. Is this the four days from the Gironde again, just mis-conveyed by later chroniclers in the wrong context?

The shape of the tin ingots described as ‘Astragali’ in Diodorus’s account seems to have been confused because vertebrae bone or knucklebone were used as gaming dice and went by that name. The shape of any discovered tin ingots from Devon and Cornwall neither resemble cubes or the knucklebone shape. There is little credibility that can be given to this hypothesis. These moulded convex and bun shaped ingots in different sizes would fit into wooden framed skin covered boats called coracles. The shape of the Ingots would be bun shaped (like those found at the head of the river Erm) with no hard corners for a few reasons and it is to this shape from which we can assume the term astralagi refers.

Naturally moulded tin ingot formed in any convienient dried rock pool next to a river where cassiterite would be mined, would be the first. Consequently, a hemispheroid that would not tear the animal skins of the local traders that transported the ingots to Ictis in their coracles is the second. There would be no need to schampher or to soften the flat surface edges of the convex shape due to ‘surface tension’ of the liquid tin as the mould cooled. By natural design, flat on one side and convex on the other, seem to be the shape of the majority of existing examples including the recent find of the ingot cargo in the Erm mouth which we will discuss shortly. This shape would make them ideal to fit between the wooden framing of any coracle and present a completely flat interior for its occupants, following the curve of the boat. This would avoid point and weight loading of any part of the skin. The exterior of the Astragali would always present to the skin face a surface unlikely to rip or damage and be kept in place by the surrounding wooden framing. By placing and packing the Astragali as a removable floor the traders would be spreading the weight throughout the coracle while at the same time creating ballast at a low centre of gravity. This would be the optimum means of transport at sea to avoid the cargo becoming loose during passage. The shape of the Astragali over time, was probably standardised by popular agreement and by convieniece to both transporter and smelter..... in moulds formed naturally eroded by rain or river used by early ‘Tinners’.... hence all the different sizes, but the shape for shipping being a secondary convienient element. The third reason as C.F.C Hawkes points out, can be deduced from Diodorus’s description of the ingots passage to the mouth of the river Rhone by horse or mule, a passage of about thirty days ‘on foot’. The ingots would be better shaped for saddle bags on these pack horses. The optimum size of the ingots would have evolved by feedback from the pilots of coracles.

The shape of the ingots probably evolved from lighting fires over dried out rock pools conveniently found everywhere next to the river, from which the Cassiterite was panned by the Bronze Age Tinners and this shape turned out to be the most practical for early sea transport.

It is not even clear whether Pytheas when he refers to coracles is referring to the foreign traders. This seems unlikely but seems to refer to the suppliers from the different river mouths transporting their tin to Ictis along the coast to the central agency described as an 'Emporium'. Certainly this would have been the easiest way to get ingots from areas downstream of the rivers running from southern Dartmoor to convey them to Ictis. The river Avon however, the effluent from which exits by the trading post of Ictis is a different story, as the tin came down by cart from Dartmoor as witnessed by Diodorus’ description of Pytheas’ eye witness account as we shall establish later.

It becomes evident that Diodorous when he writes,‘and a peculiar thing occurs concerning islands near, lying between Europe and Britain. For at high tides, the passage between being flooded, they appear as islands, but at low tide, the sea recedes and much space being exposed again dry, they are seen to be peninsulas’; has completely misled those investigators looking for the fabled island of Ictis.

The word “near” when referring to neighbouring islands has made it impossible to find a relative location on the South West coast of Devon and Cornwall. The most probable explanation of this confusion.... which leads to an impossible location to match its description…… is that it is a combination of Pytheas’ original eye witness account with that of a later traders account of passing the Channel Islands. Upon setting out from the French coast in the morning, one would see islands before dark while passing the Channel Islands, then probably having slept through the night one would arrive at another island next to the coast…… could be an explanation, but it is more likely that it is a mixture of two accounts.

Ictis is a single Island of Pytheas’ account but was misconstrued by Diodorus and other chroniclers from eyewitness accounts of traders that obviously were referring to the Channel Islands and this reference to other islands being ‘near’ is a later interpolation and misunderstanding of Pytheas’ account. Alternatively, a passenger not accustomed to navigation, the sea or the speed at which a boat travels, might lead him to believe those other islands to be in close proximity to the one at which he has arrived if they travelled through the night.

It is highly probable that Diodorous has accurately conveyed from Pytheas the detail concerning the island drying out, but then inserts his own information narrated to him from one of the overland traders who might have made the voyage to Ictis or even heard of an account or seen the Channel Islands en route to ictis. Diodorus as a Greek Sicilian from Mediterranean waters is already struggling with the concept of ‘tides’ and in his narration he deems the whole notion as “peculiar”. So having made this error and misunderstood that Ictis is situated “near” other islands, these other islands then in the same ‘peculiar tide’, become plural peninsulas’ in the narrative. To find such a location on the British South West promontory ‘near Britain’ would be impossible. However one might view the confusion of the plurality of Islands, we know that Pytheas is talking of a singular Island called Ictis to which wagons cross over when the tide recedes.

However, with the many garbled references let us stick to the account in Diodorus’s ‘Bibliotheca Historica’ for the moment and see what he has to say in the following passage relating to the Island of Ictis and the British tin trade;

“We shall give an account of the British institutions, and other peculiar features, when we come to Cæsar’s expedition undertaken against them, but we will now discuss of the tin produced there. The inhabitants who dwell near the promontory of Britain, known as Belerium, are remarkably hospitable; and, from their intercourse with other peoples merchants, they are civilized in their mode of life. These people prepare the tin, in an ingenious way, quarrying the ground from which it is produced, and which, though rocky, has fissures containing ore; and having extracted the supply of ore, they cleanse and purify it, and when they have melted it into tin ingots, they carry it to a certain island, which lies off Britain, and is called Ictis. At the ebbing of the tide, the space between this island and the mainland is left dry and then they can convey the tin in large quantities over to the island on their wagons. A peculiar circumstance happens with regard to the neighbouring islands, which lie between Europe and Britain, for at flood tide, the intermediate space being filled up, they appear as islands; but at ebb tide, the sea recedes, and leaves a large extent of dry land, and at that time, they look like peninsulas. Hence the merchants buy the tin from the natives, on Ictis and carry it over into Gaul (Galatia); and in the end after travelling through Gaul on foot about a thirty days journey, they bring their wares on horses to the mouth of the river Rhone.”

Mount Batten in Plymouth, a peninsula just off Cattwater, has been posited as a possible contender for Ictis, but it doesn't dry out at low tide and it could never have been kept secret as Strabo infers and one can see geologically it has never been separated by tidal flow....

or insular, to fit with Pytheas’ description.

The source of the Plym is at Plymhead, on the high open moorland of Dartmoorand the river from Higher Hartor to Cadover Bridge which has concentrated evidence of early settlement including burial mounds and Bronze Age hut circles.... would possibly put Mount Batten as a contender for Ictis, if indeed it had dried out at low tide to where carts could cross, as related by in the original description by Pytheas. The strip of land leading to Mount Batten was splashed on a high tide before the modern breakwater was built but this hardly results in the description of an island. Even though there is a small natural harbour.... why, one must ask was the tin taken to the island that Pytheas witnessed, but for the insular protection and the ease of landing and then loading a vessel.... both of these conveniently found at Burgh island.

Pytheas correctly estimated the circumference of Great Britain as 4000 miles and also knew the distance to be sailed from Marseille as 1050 instead of the actual distance of 1120, so he was accurate in his own estimations and figures if these are his figures. His original account would have been without error because he experienced it, unlike later second hand accounts, some of which were written by chroniclers that thought his exploits and observations not credible and actively set out to discredit him.

The Belerion mentioned by Pytheas is most likely defined as the southern promontory of Great Britain probably commencing with Salcombe in South Devon, stretching all the way down to Lands’ End. This ‘promontory’ clearly depicted on a map geographically adheres to Pytheas’ description. More rationally we can understand his definition as the start of the south west peninsula or ‘promontory’

as a description derived from a Navigator. There is also the fact that the name of Belerion tends to suggest the area defined by a people and that same area would then latterly become known as Dumnonia which included both Devon and Cornwall.

By Pytheas’ understanding, he was explaining the area south west from Salcombe and describing Belerion as such, being defined by a people. ‘The natives of this promontory area’ is the intonation from his original account discussing the people he found there....... being more than the norm, ’friendly to strangers’..... a trait still evident in the modern era. However as we move through this investigation in later chapters it is a possibility that Pytheas' promontory was defined more locally as the area extending south from a line between Torbay and Plymouth i.e the river valleys running south of Dartmoor.

BURGH ISLAND

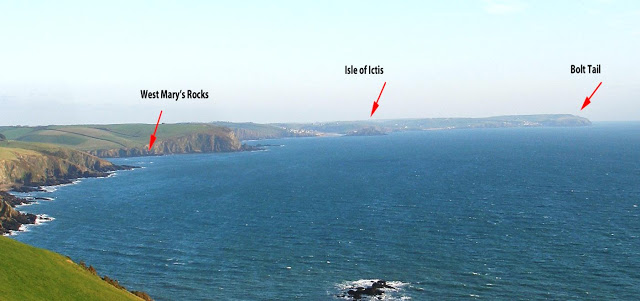

Just west of the entrance into Salcombe estuary, about 2.5 miles west of ‘Bolt tail’, there lies a small island called Burgh Island which fits Pytheas’s description exactly. Bolt head and Bolt tail (probably derived from Bel) being easily recognisable from miles out to sea with its prominent plateau like formation.... would make landfall at Ictis for any early trader relatively simple ‘eyeball navigation’.

If one considers that, to navigate in these tidal currents that relentlessly flow, (sometimes flowing in the opposite direction on the outskirts of the channel to the main mid channel flow) makes navigation hazardous. Once having passed the Channel Islands on a trip from the French coast or from an approach further west, the navigator is open to the vagaries of the current and weather.

The first compasses were made of lodestone, a naturally-magnetized ore of iron. Ancient people found that if a lodestone was suspended so it could turn freely, it would always point in the same direction toward the magnetic pole. These were later adapted as compasses made of iron needles, magnetized by stroking them with a lodestone. It is highly probable that the early navigators that were plying their trade in tin, even before Pytheas made his voyage, used these lodestones to locate the escarpment of Bolt head and Bolt Tail. There is an old mine at the base of Bolt head known as Easton’s mine in which Mundic is found (an oxidisation of pyrites).... while the unfortunate miner had hoped to find Copper. These lodes of Pyrites crystals are found throughout the whole cliff and there are several well documented accounts of Ship’s compasses being ‘swung off’ by the mass of Iron rich lodes found in the headland. The Captain of the Herzogin Cecilie fell foul of this phenomena by hitting the Ham stone.... while the ancients may have used this to their advantage in conjunction with a swinging lodestone.

Figure 10a Showing the tin Valley of the Avon, high above Ictis on Southern Dartmoor.

Old style tin streaming between these two rivers was the main industry in prehistoric times, due to the geological formation of a river on each side of a central granite escarpment. Tin is smelted from ‘cassiterite’, a mineral found in hydrothermal veins in granite, which is what had been separated by constant erosion from the Quartz, Mica and Feldspar that constitute the Granite.

This area just north of the South Hams is where we find the earliest beginnings of what was to become a global supplier of tin to the ancient world. The methods employed to extract tin from Dartmoor followed a progression from streaming through open cast mining to much later underground mining. Within ten miles from Ictis there are extensive archaeological remains of these three phases of the industry, and sites still exist that show the stages of processing that were necessary to convert the ore to tin metal. The ordnance survey map provides a snapshot showing the evolution from the early Bronze Age through to the 1300’s AD.

The once very extensive alluvial deposits of tin ore, which were the first deposits to be mined in the two rivers…… once existed in lodes before the errosion caused from the ice melt higher up on Darmoor. The run off has left the steep sided valleys which evidence the vast quantity of ore that must originally have been eroded and gathered on the valley floor. The first occupants, just panning the river beds due to cassiterite’s specific gravity, would have sourced it all the way down the Erm and Avon Valleys.

The legendary island of Ictis which is called ‘Burgh Island’ today, stands at the mouth of the Avon River on the opposite shore to the small hamlet of Bantham. The Island of Ictis, first heard of in the chronicles of the ancient writers, was probably coined from the Greek ikhthys meaning fish, because up until recently Burgh Island was renowned for the shoals of pilchards that congregated naturally around it in Bigbury Bay. It seems that Pytheas referred to the Island asikhthys island or ‘fish island’ (as it was probably called back then by the locals)…… and then later chroniclers termed it the Island of Ictis. The shoals of pilchards in the bay were legendary well into the 18th century…… fishing fleets said to have made catches of 12 million fish in a single day. The pilchards were cured with salt and were either pressed for oil or shipped by the barrel load to Europe. It seems extraordinary that the one Island described by Pytheas as Fish Island and renowned for its huge shoals that sometimes darkened the whole bay, would not be associated with the Greek word ikhthys…… also being the only tidal island on the southern promontory as described by Pytheas…… and especially situated just 10 miles from the huge alluvial tin deposits that existed on southern Dartmoor.

Tin was transported from this small island over to France by French traders and further by international traders such as the Phoenicians…… since around 1000 BC until around 30 BC. This trade must have been seriously interfered with by Julius Caesar's expeditions in 55 and 54 BC. The recent find of tin ingots at the mouth of the River Erm 2.5 miles distant, confirms Burgh Island as Ictis and its link with the tin trade. In a small area near Bantham that has recently been archaeologically excavated, Amphorae were found and also other signs of active trade with France and most probably Phoenician traders from an early era.

In another recent discovery on the Eastern shore at Wash Gully, 300 yards off the coast on the approaches to the Salcombe estuary, divers recently uncovered 259 copper ingots, a bronze leaf sword and 27 tin ingots. The wreck of an old trading vessel found there, dates from around 900BC and measures 40ft long to approximately 6ft wide and is constructed from timber planks. It is thought to have been powered by a crew of 15 seamen with paddles, but it seems likely even at this early stage, some form of ‘windage’ would have been employed in a fair wind.

There is more physical archaeological evidence along this small stretch of coast, between the mouth of the river Erm and Salcombe, to add credibility to Burgh island being synonymous with Ictis and its links with the Tin industry. The Archeological evidence indicates that there was considerable trade in tin ore and this (according to Pytheas) being shipped abroad from an early period. Although the copper ingots of the Salcombe wreck are said to have come from Europe; it does not necessarily indicate that the copper was being imported. A craft of this size may have been on a scouting mission to pick up ingots from Ictis, having heard of it as a tin depot from those further along the coast or the tin ingots could have come from Ictis before it was wrecked.

There is little evidence to show anywhere on the promontory of Belerion that the actual smelting of bronze took place to any industrial degree, but it is possible that these copper ingots found off Salcombe, could have been traded with the locals for the rarer commodity of tin. Although copper was mined to the south-west of Dartmoor, these mines are of a much later date than the wreck in question. The ‘Blow Houses’ found up behind the Avon dam are part of the tin smelting process and were probably only used as such and not employed to make bronze and these also were of a much later date.

Pytheas was one of the first people to give a report of Stonehenge while he visited the British Isles and took measurements of the Sun’s declination in Britain at different points in the year to further his astronomical studies. He was also probably one of the first Greeks to give an account of the tidal activity which he had learnt (from the Britons), was caused by the moon, the tide of course being virtually non-existent in Mediterranean waters. This was 1800 years before Galileo was taken to task in asserting that the world was round. Galileo was denounced at theRoman Inquisition in 1615 AD by the Catholic Church, which condemned heliocentrism (the idea that the world was a globe) as ‘false and contrary to Scripture’. This does seem quite extraordinary when the Sun and Moon are obviously round and navigational knowledge had existed for nearly two thousand years.

Some of the ancient writers like Diodorus do not even mention Pytheas by name, but refer to his comments alone. Pliny, who is using Timaeus as a source says, “there is an island named Mictis where tin is found, and to which the Britains cross”. He uses the word ‘proveniat’ which commentators have assumed as meaning that Tin was actually mined at Ictis but the real meaning is ‘provend’ as a supplier which matches the concept of ‘Emporium’ which many translators, chroniclers and commentators have puzzled over the words meaning in connection with Ictis. The reasoning behind this choice of word is very misleading, since there was no tin mined at the island as later chroniclers have wrongly intimated. The tin was just stored there, (large quantities of tin being transferred to the island by cart)..... this point being of great importance as the reader will become aware shortly.

The ‘crossing’, mentioned by most chroniclers is in reference to the sandbar or causeway evidenced today at Burgh island, but Pliny who obviously never went to the island, implying a large stretch of land to be crossed.

Diodorus writes also that tin is brought to the island of Ictis, where there is an Emporium, literally being translated as a ‘marketplace or agency’ and this is the definition which defines the role of Ictis.

Polybius was probably a source to Strabo for some details concerning Ictis and Strabo relates that an Emporium on the Island of Corbulo at the mouth of the river Loire was associated with the Island of Ictis, so here again the real picture is made more difficult to identify Ictis. Strabo also infers that Ictis, and Corbulo are different names for the same island, so there is much confusion as the Chinese whisper effect has confused its location. Possibly, Strabo never saw a copy of Pytheas and sourced most of his material from Polybius. Diodorus on the other hand seems to have read Timaeus, sourced from Pytheas’ original, which Polybius seems to have read also. It would appear that Strabo did not read Pytheas first hand, (or he would not have referred to Polybius) and is probably accountable for much of the Chinese whispers effect.

Pliny calls the island, Mictis, mictim or mictin which indicates that he has translated directly from Timaeus, changing the case ending from the Greek at different times, but he was struggling to make the distinction between Cassiteris and Ictis because he actually writes “INSULAM MICTIM,”.Other writers such as Suetonius have actually referred to the island as Vectis, which has obviously led to confusion with the Isle of Wight which was known in the Roman world as Vectis and used to be pronounced ‘ouectis’ which obviously sounds similar to Ictis.

It would appear taking into account archaeological evidence of early tin production that one would need to look for an island somewhere between Salcombe and Lands’ End that dries out at low tide and becomes a peninsula. We should ignore the information about Ictis having been surrounded by other islands close by, as there is no such location near a tidal Island peninsula. We should account it as later misunderstanding of a muddled confusion from a second or third hand account concerning the Channel Islands. Other considerations to achieve a practical location for Ictis should consider navigational ease or constraints and overland transportation; for by Pytheas’ account, these were large consignments of tin being moved. It would appear therefore, that the story as a whole has become a confused interpretation over the years, comprised of rationalisations and interpolations of the original account.

Diodorus relates that Ictis was dry at low water and “the natives conveyed to it wagons, in which were large quantities of tin”. This and the fact that the Island is connected by a causeway at low tide, across which these wagons convey the tin are the essential facts relayed by Pytheas himself.

The fact that large quantities of tin at this stage in 350BC and more specifically before that, was produced in Devon can be seen archeologically. It makes little practical sense to think that the Isle of Wight, Hengistbury point, Looe island, St. Michael's Mount or Thanet are even viable candidates for the island of Ictis.

The quantities mentioned and the heavy transport loads involved from Dartmoor as far as the Isle of Wight over 100 miles away should exclude any further mention being given as a credible location for Ictis.... especially given the transport risks of such a valuable commodity. The problem with all the previous possible candidates for the Island of Ictis is that scholars or researchers have always used information selectively to support their own views on the location. This has been easily achieved due to corruption or disbelief in Pytheas' original text.

It is known that tin mining had first started in between the Erm and Avon estuary in the early British Bronze Age. There is ample archaeological evidence to show that tin streaming existed high up on the moors behind South Brent at Shipley Bridge on the Avon, at least to 1600BC and probably beyond.

Strabo relates the fact that the people who control the Island of Ictis took great pains to hide the business of the island from Roman vessels seen on that part of the coast.

It is probable that the early wagoneers who brought the tin down through 'Loddiswell' to the Island of Ictis for sale, could no longer keep secret their route down from Dartmoor after the Romans arrived and this may have been the root cause of the eventual end of the islands monopoly as the place of primary export.

The word ‘Emporium’ indicates that Ictis acted as a market, which indicates some sort of central agency, trading post or even monopoly from which the tin was traded. This would make sense practically, understanding that a trading vessel would not want to wait around for the tin to be brought down from the various tin streamers up on the moors. This leads to a natural conclusion that Ictis maintained some sort of vault or storage area from which tin was dispersed as trading vessels arrived. This would also concur with the ‘wagon loads’ of Pytheas' eye witness account. Vessels arriving from abroad, could expedite their business by landing and loading on the sand causeway and if the winds were fair, return home without a long wait in the anchorage at Bantham.