2006

4-29-06

400 Dolphins

Wash Up Dead Off African Coast

By ALI SULTAN,

AP

ZANZIBAR,

Tanzania (April 29, 2006) - Scientists

tried to discover Saturday why

hundreds of dolphins washed up dead

on a beach popular with tourists on

the northern coast of Zanzibar.

Among

other possibilities, marine

biologists were examining whether

U.S. Navy sonar threw the animals

off course.

Villagers

and fishermen were burying the

remains of the roughly 400

bottlenose dolphins, which normally

live in deep offshore waters but

washed up Friday along a 2 1/2-mile

stretch of coast in Tanzania's

Indian Ocean archipelago.

The

animals may have been disturbed by

some unknown factor, or poisoned,

before they became stranded in

shallow waters and died, said

Narriman Jiddawi, a marine biologist

at the Institute of Marine Science

of the University of Dar es Salaam.

Experts

planned to examine the dolphins'

heads to assess whether they had

been affected by military sonar.

Some

scientists surmise that loud bursts

of sonar, which can be heard for

miles in the water, may disorient or

scare marine mammals, causing them

to surface too quickly and suffer

the equivalent of what divers call

the bends - when sudden

decompression forms nitrogen bubbles

in tissue.

A

U.S. Navy task force patrols the

coast of East Africa as part of

counterterrorism operations. A Navy

official was not immediately

available for comment, but the

service rarely speaks about the

location of submarines at sea.

A

preliminary examination of their

dolphins' stomach contents failed to

show the presence of squid beaks or

other remains of animals hunted by

dolphins.

That

was an indication that the dolphins

either had not eaten for a long time

or had vomited, Jiddawi said.

Their

general condition, however, appeared

to show that they had eaten

recently, since their ribs were not

clearly visible under the skin, she

said.

Although

Jiddawi said Friday that poisoning

had been ruled out, experts were

preparing to further examine the

dolphins' stomachs for traces of

poisonous substances such as toxic

"red tides" of algae.

Zanzibar's

resorts attract many visitors who

come to watch and swim with wild

humpback dolphins, which generally

swim closer to shore than the

Indo-Pacific bottlenose.

The

humpbacks, bottlenose, and spinner

dolphins are the most common species

in Zanzibar's coastal waters.

The

most conclusive link between the use

of military sonar and injury to

marine mammals was observed from the

stranding of whales in 2000 in the

Bahamas. The U.S. Navy later

acknowledged that sonar likely

contributed to the stranding of the

extremely shy species.

"These

animals must have been disoriented

and ended up in shallow waters,

where they died," Abdallah Haji,

a 43-year-old fisherman, said

Saturday as he helped bury the

dolphins near the bloodied beach.

Residents

had cut open the animals' bellies to

take their livers, which they use to

make waterproofing material for

boats.

"We

have never seen this type of dolphin

in our area," said Haji, who

said he has fished in Zanzibar's

waters for more than two decades.

04/29/06 16:37

EDT

Copyright 2006

The Associated Press.

Mass dolphin and

whale beaching in Australia

Take a look at this

article from the Sydney

Morning Herald:

Whale

toll rises: second pod found

dead

97 whales and dolphins

have beached themselves in

the past 24 hours. What could

cause something like this??

A second pod of whales

offshore from the site of a mass

beaching on King Island in Bass

Strait has died, officials said.

The 17 pilot whales were

confirmed dead by wildlife

officers this morning, taking to

total toll of dead whales and

dolphins to 97 in the past 24

hours, Tasmanian Department of

Primary Industry, Water and

Environment spokesman Warwick

Brennan said.

A mixed pod of long-finned

pilot whales and bottle-nosed

dolphins beached on the remote Sea

Elephant Beach, north of Naracoopa,

yesterday.

Rescuers counted the bodies

of 55 whales and 25 dolphins by

this morning.

There were no further

survivors in the area, Mr Brennan

said.

Meanwhile, 50 pilot whales

have reportedly beached on Maria

Island off Tasmania's east coast,

a government spokesman said.

Rescuers were on their way

to the area, the spokesman said.

The cause of the strandings was

not known.

AAP

Right

after this event, the tsunami in

Sri Lanka occurred on December 26,

2004.

See:

TSUNAMI

IN OUR FUTURE

Sunday,

December 26, 2004. Tidal

waves, or tsunami, often

set off by undersea

earthquakes, have caused

several major disasters in

coastal communities over

...

www.greatdreams.com/weather/tsunami_in_our_future.htm |

EARTHQUAKE

IN SRI LANKA

29

December 2004. The death

toll in the tsunami

disaster soared past

100000 today - and is set

to climb higher. Look here

too. • Gallery: sorrow

and relief ...

www.greatdreams.com/sri-lanka.htm

December 16, 2006 - Fungal

Infection Killed 2,500

Mallard Ducks in Idaho.

Some

of the 2,500 mallard ducks

that died

between December 8 and 13,

2006, along Land Creek

Springs

near Oakley, Idaho. Photo

courtesy Idaho Fish and

Game.

|

"We've

never seen anything

like this - ever. In

doing some research,

we can’t find any

other die-offs of

this magnitude with

mallard ducks

in the United

States."

- David

Parrish, Idaho Dept.

of Fish and Game |

|

In a six day period

between December 8 and

December 13, 2006, the Idaho

Fish and Game Department

received reports of dead

mallard ducks on the Land

Creek Springs waterway near

Oakley in the Sawtooth

National Forest region of

south central Idaho. By

December 13th, the death

count was up to 2,500 ducks,

unprecedented in Idaho

wildlife history. By

December 14, the first

laboratory results from

several agencies are

expected and I talked about

the unprecedented die-off

with David Parrish, Magic

Valley Regional Supervisor

in the Idaho Department of

Fish and Game where he has

been employed for twenty-six

years.

"Ducks

Died of Fungal

Infection

State and federal

officials have

confirmed that

about 2,500

mallard ducks

found dead

southeast of

Burley, died of an

acute fungal

infection.

The official cause

of death is acute

aspergillosis, a

respiratory tract

infection caused

by a fungus

commonly found in

soil, dead leaves,

moldy grain,

compost piles, or

in other decaying

vegetation.

Test results from

University of

Idaho’s Caine

Veterinary

Teaching Center in

Caldwell confirmed

the presence of

the fungus in

tissue samples

taken from the

ducks this week.

The results

confirm

preliminary

diagnoses at two

other wildlife

health labs in

Washington and

Wisconsin.

The fungus can

cause respiratory

tract infections

in birds that

inhale the spores.

The most likely

source of the

spores for these

ducks is moldy

grain, but no

specific site has

been found as the

source.

Waterfowl die-offs

are common and

many happen in the

United States

every year. During

the past six

months, 16 events

each involving

more than 1,000

birds occurred.

Testing for

diseases is a

routine part of

the investigation

of waterfowl

die-offs.

The first dead

ducks were found

by a hunter

Friday, December

8, along Land

Creek Springs near

Oakley. Idaho

Department of Fish

and Game was

notified, and

conservation

officers found 10

dead ducks near

the spring and

along the stream’s

edge.

Officers returned

to the area on

December 10 to

find more than 500

dead ducks. By the

end of clean-up

operations

Thursday morning,

the number had

grown to about

2,500. Though a

small proportion

of the duck

population in

Idaho or the

United States, the

number of dead

birds in this

die-off is unusual

for Idaho.

Officials

initially

considered it

unlikely that

avian influenza

was the cause of

this die-off.

Widespread testing

of waterfowl in

fall of 2006 has

not found the

highly pathogenic

avian influenza

strain H5N1 in the

United States.

Tissue samples

from dead birds

were not

consistent with

avian influenza,

but as a

precaution samples

were sent to U.S.

Geological

Survey’s National

Wildlife Health

Center in

Wisconsin for

testing.

Results from the

first two groups

of ducks tested

confirmed that

they did not have

the highly

pathogenic avian

influenza strain

H5N1 that is

currently of

concern in Asia,

Europe, the Middle

East and Africa.

Results from

additional tests

are pending.

The Idaho

Department of

Environmental

Quality,

Department of

Agriculture and

the U.S. Fish and

Wildlife Service

helped with the

investigation of

this outbreak.

Hunters are

advised not to

kill any obviously

sick animals,

including ducks

and other

waterfowl."

David

Parrish, Magic

Valley Regional

Supervisor, Idaho

Department of Fish

and Game (employed

for 26 years),

Jerome, Idaho:

"We first

got a report of

waterfowl mortality

on the site back on

Friday, December 8,

2006. We had a

conservation officer

dispatched to the

area and he found 10

dead ducks. We

cleaned those up.

We got another

call from a hunter

on Sunday afternoon,

Dec. 10, about dead

ducks in the same

general area. We

dispatched an

officer again. At

that point in time,

he found about 500

mallard ducks that

were dead.

By Monday

morning, December

11, we sent staff

out on site. We

found roughly 1500

dead mallards and by

yesterday afternoon

after we picked up

all of the

carcasses, the count

was up to about 2500

mallard ducks.

|

We have

never seen a

die-off like

this before

in Idaho. In

doing some

research, we

can’t find

any other

die-offs of

this

magnitude

with mallard

ducks in the

United

States. We

have a

number of

agencies

that are

investigating

the cause of

death and

looking at

potential

mortality

factors. We

have our

Dept. of

Environmental

Quality (DEQ),

the South

Central

District

Health

Office, the

Idaho Dept.

of

Agriculture.

At the

federal

level, we

have the

Dept. of

Homeland

Security

involved.

There are a

number of

agencies and

they are all

looking at a

number of

potential

factors. DEQ

has taken

water and

soil samples

from the

area. The

Dept. of

Agriculture

has taken

pesticide

samples. Our

agency is

taking

tissue

samples and

has sent

them off to

a number of

labs. |

|

But the ducks

that we’ve done

necropsies on have

shown abscesses on

the lungs, which

could be causing the

respiratory

distress. According

to our veterinarian,

Dr. Mark Drew, at

our health lab, he

said that the ducks

he has looked at

have not shown the

classical signs of a

virus or influenza

type outbreak. |

|

|

Dead

birds

fall

from the

skies in

Australia

and

America

London,

Jan.11,

2007 (ANI):

Two

towns,

in two

separate

continents,

have

reported

the

mysterious

dropping

of

thousands

of dead

birds

out of

the sky.

Baffled

wildlife

officials

were

quoted

by the

Daily

Mail as

saying

that

three

weeks

ago

thousands

of

crows,

pigeons,

wattles

and

honeyeaters

fell out

of the

sky in

Esperance,

Western

Australia.

Last

week,

dozens

of

grackles,

sparrows

and

pigeons

dropped

dead on

two

streets

in

Austin,

Texas.

Veterinarians

in both

countries

have

been

unable

to

establish

a cause

of death

-

despite

carrying

out a

large

number

of

autopsies

on the

birds.

The

officials,

however,

have

ruled

out the

possibility

of the

deaths

having

been

caused

by a

severe

storm,

which

recently

struck

the

area.

"We

estimate

several

thousand

birds

are

dead,

although

we don't

have a

clear

number

because

of the

large

areas of

bush

land.

It's

very

substantial,"

the

tabloid

quoted

District

Nature

Conservation

Coordinator

Mike

Fitzgerald,

as

saying.

Birds

Australia,

the

country's

largest

bird

conservation

group,

said it

had not

heard of

a

similar

occurrence,

and

described

it as a

most

unusual

event.

Esperance

resident

Michelle

Crisp,

who

normally

sees

hundreds

of birds

roosting

in her

garden,

counted

80 dead

ones in

one day.

In

Texas,

officials

are also

working

on the

toxic

poisoning

theory.

Adolfo

Valadez,

medical

director

for

Austin

and

Travis

County

Health

and

Human

Services,

said it

might be

weeks

before

any

conclusive

results

were

known.

Such was

the

concern

that the

birds

suffered

deliberate

toxic

poisoning

that

several

streets

were

closed

in

Austin

while

police

and fire

crews

checked

the area

for any

substance

that

might be

of harm

to

humans.

Federal

officials

in

Washington

said

they

were

monitoring

the

situation,

but a

spokesman

for the

Department

of

Homeland

Security

said:

"There

is no

credible

intelligence

to

suggest

an

imminent

threat

to the

homeland

or

Austin

at this

time." (ANI)

Austin looks for answers after 63 dead birds close downtown

Cause unknown, but no threat to humans seen, health officials say

By Emily Ramshaw

The Dallas Morning News

Copyright 2007 The Dallas Morning News

AUSTIN, Texas — Public health officials were scratching their heads over what killed more than 60 grackles, pigeons and sparrows found dead along Congress Avenue near Texas' Capitol on Monday morning, prompting a downtown lockdown that scrambled traffic and kept thousands of employees home from work.

By early afternoon, they had determined that whatever killed the birds wasn't harmful to humans, and 10 blocks in the heart of downtown were reopened.

"We've have no information that leads us to believe that there is any threat," Michael McDonald, Austin assistant city manager for public safety, said during a news conference. "We are going to be conducting further analysis."

Authorities said early necropsies indicated that bird flu is not the culprit and that West Nile virus is highly unlikely, because the disease is seasonal. Air tests were negative for natural gas and other chemicals, and the birds' feathers showed no signs of pesticides. Officials all but ruled out environmental factors; the city had no inclement weather.

Officials said they believe the birds were probably poisoned or suffered from a bacterial infection. A determination will take days or weeks.

The dead birds were first reported around 3 a.m., prompting a public health emergency that forced officers, ambulances and hazardous materials teams to descend on and cordon off downtown.

Of the 63 dead birds, most were found on Congress Avenue several blocks south of the Capitol, officials said. Congress Avenue leads up to the Capitol, which did not close.

"It's not uncommon for birds to die in groups," Mr. McDonald said. "What's uncommon is for it to happen in the downtown area."

No human illness or injury was reported, though Chris Callsen, assistant director of Austin-Travis County Emergency Medical Services, said two officers on the scene reported feeling sick this morning. No one was transported to the hospital.

Emergency rooms have reported no unusual ailments, said Dr. Adolfo Valadez, Director of Austin's Department of Health and Human Services.

"There is currently not a threat to the public health," Dr. Valadez said.

Early-morning passers-by said the birds first began acting strange — wandering aimlessly in the street, attempting to fly and making crash landings — and then dropped like flies.

For most of the morning, downtown Austin was tangled in stop-and-go traffic and blinking emergency lights. Haz-mat teams in yellow plastic suits and rubber boots patrolled Congress Avenue, collecting dead birds and checking the roofs of office buildings for more. The birds are being sent to virology centers at Texas A&M University and in Ames, Iowa, for further testing.

Barn owls dying by thousands along I-84

Article Date: 2007-01-05 Source: http://www.ktvb.com Comments: 0

By Robbie Johnson

BOISE - If you drive down the interstate east of Boise you may spot some of the hundreds of dead owls that are being reported.

The owls are being hit by vehicles in unusually high numbers and so far no one is certain why such a large amount is dying.

Barn owl deaths are becoming extremely common along Interstate 84 in southern Idaho. It tends to occur all year long, but peaks in the wintertime. And in the past couple of years the situation has gotten worse.

The images of the dead owls in the video of this story may be disturbing to some.

Experts think the owls are hunting for prey at night along the interstate - flying low and in front of vehicles, and ultimately getting hit.

And the large number of deaths was enough of a concern that a Boise State University professor began a small study to find out just how many were dying. The numbers are startling.

"Thousands per year seem to be getting killed, and that suggests that there are probably a lot of barn owls in our area. But it also suggests it has the potential to be a really important mortality factor for them and start to effect their population, so there might be some conservation concern for them," said Jim Belthoff, BSU biology professor.

Boise State has three freezers full of dead owls that they've collected during the three-year study, which just wrapped up.

Most of them are young and were healthy when they died. Some even had rodents in their talons.

The next step will be to try to minimize the deaths.

One plan is to get a nest box program going.

Another is to seek money for highway signs that warn people about the owls - a lot like deer crossing signs.

Work is still being done to better determine why the birds are putting themselves in the path of vehicles in such large numbers. |

Jan. 21, 2007 5:11

10 dolphins stuck in NY creek die despite efforts

By ASSOCIATED PRESS

EAST HAMPTON, New York

The number of dolphins who have died since being trapped in a shallow creek off eastern Long Island has risen to 10, a rescue leader said.

About 20 of the "common dolphins" were first sighted about 11 days ago in the Northwest Harbor cove, which is north of East Hampton, about 100 miles (160 kilometers) east of New York City. Eight dolphins swam to safety earlier in the week after being coaxed out of the cove, and three were spotted Friday. Officials do not know how many are still alive.

|

More than 80 people have been involved in the rescue effort. The 10th dolphin's body was found midmorning Saturday, officials said.

THE BEE DILEMMA

Report links Bayer pesticide to bee deaths

A new French report has found a significant risk to bees from a Bayer product containing the active ingredient imidacloprid.

A report on bee-deaths, published by the French Comité Scientifique et Technique (CST), shows that the use of the pesticide Gaucho containing the active substance imidacloprid is jointly responsible for the death of hundreds of thousands of bee colonies. Environmental and beekeeper unions are calling for a ban on the agricultural toxin.

The summary of the report states: ‘The results of the examination on the risks of the seed treatment Gaucho are alarming. The treatment of seeds by Gaucho is a significant risk to bees in several stages of life.’ The 108-page report was made by order of the agricultural ministry of France, by the universities of Caen and Metz as well as by the Institut Pasteur.

The use of Gaucho on sunflowers was forbidden in France four years ago because of the high risk to bees. After this bee-deaths did not decrease noticeably – beekeepers are blaming this on the extensive use of agricultural toxins in maize cultivation. The concluding report of the CST backs up this theory: ‘Concerning the treatment of maize-seeds by Gaucho, the results are as alarming as with sunflowers. The consumption of contaminated pollen can lead to an increased mortality of caretaking bees, which can explain the persisting bee-deaths even after the ban of the treatment on sunflowers’.

The pesticide Gaucho is produced by the German Bayer group. With an annual turnover of more than 500 million Euros this is the group’s top selling agricultural agent. Critics assume that the high sales figures are the reason why the company is contesting a ban on its use.

The theory stated by bee institutes, that infestation by Varroa mites could be responsible for bee-deaths, is questioned by Fridolin Brandt of the Coalition against Bayer-Dangers: ‘We have been concerned with Varroa mites since 1977, and for decades they have not been a danger. It is the extensive use of pesticides and the accompanying weakening of the bees which is leading to the bee-deaths.’ Brandt has been a full-time beekeeper for more than 30 years.

Maurice Mary, spokesman of the French beekeepers-union Union National d'Apiculteurs (UNAF): ‘Since the first application of Gaucho we have had great losses in the harvest of sunflower honey. Since the agent is staying in the soil for up to three years, even untreated plants can contain a concentration which is lethal for bees.’ The UNAF, representing about 50,000 beekeepers is calling for a total ban of Gaucho, following the presentation of the CST report.

The Deutsche Berufsimkerbund (DBIB) and the Coalition against Bayer-Dangers are also calling for a ban on its use. In Germany, imidacloprid is used mainly in the production of rape, sugar beet and maize. The situation in German agriculture is comparable to the French: in the past few years almost half of the bee-colonies have died, which has led to a loss of output of several thousand tonnes of honey per year. Furthermore, because bees do the most pollination, there are also losses of output on apples, pears and oilseed rape.

Press release from Coalition against Bayer-Dangers, CBGnetwork@aol.com, http://www.cbgnetwork.org/. Contact CBG Network for copies of the 108-page report of the Comité Scientifique et Technique (in French) and a statement by the Coordination des Apiculteurs de France (in English). See also page 22.

[This article first appeared in Pesticides News No. 62, December 2003, page 17]

- Any information here in is for educational purpose only, it may be news related, purely speculation or someone's opinion, If health related always consult with a qualified health practitioner before deciding on any course of treatment, especially for serious or life-threatening illnesses.

**COPYRIGHT NOTICE**

In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107,

any copyrighted work in this message is distributed under fair use without profit or payment to those who have expressed a prior interest in receiving the included information for non-profit research and educational purposes only. http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

-~----------~----~----~----~------~----~------~--~---

Subject: The "highly preliminary" results (bees)

A possibility --nothing more.....

http://www.ktvu.com/news/13202905/detail.html?rss=fran&psp=news

SAN FRANCISCO -- A fungus that killed bee colonies across Europe and Asia may be to blame for the current collapse of bee colonies in the U.S. and Canada, researchers said.

The sudden deaths of the buzzing insects, a condition called Colony Collapse Disorder, has disturbed beekeepers, scientists and farmers who depend on bees for pollination.

The "highly preliminary" results announced Wednesday showed evidence of the single-celled parasite called Nosema ceranae on a few hives taken from Merced County for testing, said Joe DeRisi, a biochemist at the University of California, San Francisco, who found the SARS virus in 2003.

DeRisi used a technique known as "shotgun sequencing," that allows rapid reading of a genetic code and then matches it to computerized libraries of known genes from thousands of germs.

Other scientists said Wednesday they had found the fungus in hives from around the country but were quick to point out the parasite also was found in healthy bees. Researchers found two other fungi and a half- dozen viruses in dead bees.

"By itself, (N. ceranae) is probably not the culprit," said entomologist Diana Cox-Foster of Pennsylvania State University. "But it may be one of the key players."

Cox-Foster and about 60 other researchers gathered this week in Washington, D.C., to discuss Colony Collapse Disorder.

Scientists have not ruled out other factors such as pesticides or inadequate food resources following a drought, she said.

Weather, pesticides and infestations have wiped out significant numbers of colonies in the past, but the current loss appears unprecedented. Worried agriculture officials estimate about a quarter of the 2.4 million commercial colonies across the U.S. have been lost since fall.

http://www.ktvu.com/news/13202905/detail.html?rss=fran&psp=news

MYSTERY Honeybee colonies around the nation are collapsing. Above, a beekeeper in Loxahatchee, Fla.

By ALEXEI BARRIONUEVO

April 24, 2007

BELTSVILLE, Md., April 23 - What is happening to the bees?

Multimedia Map

Disappearing Bees

Kalim A. Bhatti for The New York Times

SUSPECTS The volume of theories to explain the collapse of honeybee populations "is totally mind-boggling," said Diana Cox-Foster, an entomologist at Penn State.

More than a quarter of the country's 2.4 million bee colonies have been lost - tens of billions of bees, according to an estimate from the Apiary Inspectors of America, a national group that tracks beekeeping. So far, no one can say what is causing the bees to become disoriented and fail to return to their hives.

As with any great mystery, a number of theories have been posed, and many seem to researchers to be more science fiction than science. People have blamed genetically modified crops, cellular phone towers and high-voltage transmission lines for the disappearances. Or was it a secret plot by Russia or Osama bin Laden to bring down American agriculture? Or, as some blogs have asserted, the rapture of the bees, in which God recalled them to heaven? Researchers have heard it all.

The volume of theories "is totally mind-boggling," said Diana Cox-Foster, an entomologist at Pennsylvania State University. With Jeffrey S. Pettis, an entomologist from the United States Department of Agriculture, Dr. Cox-Foster is leading a team of researchers who are trying to find answers to explain "colony collapse disorder," the name given for the disappearing bee syndrome.

"Clearly there is an urgency to solve this," Dr. Cox-Foster said. "We are trying to move as quickly as we can."

Dr. Cox-Foster and fellow scientists who are here at a two-day meeting to discuss early findings and future plans with government officials have been focusing on the most likely suspects: a virus, a fungus or a pesticide.

About 60 researchers from North America sifted the possibilities at the meeting today. Some expressed concern about the speed at which adult bees are disappearing from their hives; some colonies have collapsed in as little as two days. Others noted that countries in Europe, as well as Guatemala and parts of Brazil, are also struggling for answers.

"There are losses around the world that may or not be linked," Dr. Pettis said.

The investigation is now entering a critical phase. The researchers have collected samples in several states and have begun doing bee autopsies and genetic analysis.

So far, known enemies of the bee world, like the varroa mite, on their own at least, do not appear to be responsible for the unusually high losses.

Genetic testing at Columbia University has revealed the presence of multiple micro-organisms in bees from hives or colonies that are in decline, suggesting that something is weakening their immune system. The researchers have found some fungi in the affected bees that are found in humans whose immune systems have been suppressed by the Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome or cancer.

"That is extremely unusual," Dr. Cox-Foster said.

Meanwhile, samples were sent to an Agriculture Department laboratory in North Carolina this month to screen for 117 chemicals. Particular suspicion falls on a pesticide that France banned out of concern that it may have been decimating bee colonies. Concern has also mounted among public officials.

"There are so many of our crops that require pollinators," said Representative Dennis Cardoza, a California Democrat whose district includes that state's central agricultural valley, and who presided last month at a Congressional hearing on the bee issue. "We need an urgent call to arms to try to ascertain what is really going on here with the bees, and bring as much science as we possibly can to bear on the problem."

So far, colony collapse disorder has been found in 27 states, according to Bee Alert Technology Inc., a company monitoring the problem. A recent survey of 13 states by the Apiary Inspectors of America showed that 26 percent of beekeepers had lost half of their bee colonies between September and March.

Honeybees are arguably the insects that are most important to the human food chain. They are the principal pollinators of hundreds of fruits, vegetables, flowers and nuts. The number of bee colonies has been declining since the 1940s, even as the crops that rely on them, such as California almonds, have grown. In October, at about the time that beekeepers were experiencing huge bee losses, a study by the National Academy of Sciences questioned whether American agriculture was relying too heavily on one type of pollinator, the honeybee.

Bee colonies have been under stress in recent years as more beekeepers have resorted to crisscrossing the country with 18-wheel trucks full of bees in search of pollination work. These bees may suffer from a diet that includes artificial supplements, concoctions akin to energy drinks and power bars. In several states, suburban sprawl has limited the bees' natural forage areas.

So far, the researchers have discounted the possibility that poor diet alone could be responsible for the widespread losses. They have also set aside for now the possibility that the cause could be bees feeding from a commonly used genetically modified crop, Bt corn, because the symptoms typically associated with toxins, such as blood poisoning, are not showing up in the affected bees. But researchers emphasized today that feeding supplements produced from genetically modified crops, such as high-fructose corn syrup, need to be studied.

The scientists say that definitive answers for the colony collapses could be months away. But recent advances in biology and genetic sequencing are speeding the search.

Computers can decipher information from DNA and match pieces of genetic code with particular organisms. Luckily, a project to sequence some 11,000 genes of the honeybee was completed late last year at Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, giving scientists a huge head start on identifying any unknown pathogens in the bee tissue.

"Otherwise, we would be looking for the needle in the haystack," Dr. Cox-Foster said.

Large bee losses are not unheard of. They have been reported at several points in the past century. But researchers think they are dealing with something new - or at least with something previously unidentified.

Globules in a bee's gut may indicate lethal pathogens.

Multimedia

Map

Cross-sections of a diseased bee thorax, left, and a healthy one.

"There could be a number of factors that are weakening the bees or speeding up things that shorten their lives," said Dr. W. Steve Sheppard, a professor of entomology at Washington State University. "The answer may already be with us."

Scientists first learned of the bee disappearances in November, when David Hackenberg, a Pennsylvania beekeeper, told Dr. Cox-Foster that more than 50 percent of his bee colonies had collapsed in Florida, where he had taken them for the winter.

Dr. Cox-Foster, a 20-year veteran of studying bees, soon teamed with Dennis vanEngelsdorp, the Pennsylvania apiary inspector, to look into the losses.

In December, she approached W. Ian Lipkin, director of the Greene Infectious Disease Laboratory at Columbia University, about doing genetic sequencing of tissue from bees in the colonies that experienced losses. The laboratory uses a recently developed technique for reading and amplifying short sequences of DNA that has revolutionized the science. Dr. Lipkin, who typically works on human diseases, agreed to do the analysis, despite not knowing who would ultimately pay for it. His laboratory is known for its work in finding the West Nile disease in the United States.

Dr. Cox-Foster ultimately sent samples of bee tissue to researchers at Columbia, to the Agriculture Department laboratory in Maryland, and to Gene Robinson, an entomologist at the University of Illinois. Fortuitously, she had frozen bee samples from healthy colonies dating to 2004 to use for comparison.

After receiving the first bee samples from Dr. Cox-Foster on March 6, Dr. Lipkin's team amplified the genetic material and started sequencing to separate virus, fungus and parasite DNA from bee DNA.

"This is like C.S.I. for agriculture," Dr. Lipkin said. "It is painstaking, gumshoe detective work."

Dr. Lipkin sent his first set of results to Dr. Cox-Foster, showing that several unknown micro-organisms were present in the bees from collapsing colonies. Meanwhile, Mr. vanEngelsdorp and researchers at the Agriculture Department lab here began an autopsy of bees from collapsing colonies in California, Florida, Georgia and Pennsylvania to search for any known bee pathogens.

At the University of Illinois, using knowledge gained from the sequencing of the bee genome, Dr. Robinson's team will try to find which genes in the collapsing colonies are particularly active, perhaps indicating stress from exposure to a toxin or pathogen.

The national research team also quietly began a parallel study in January, financed in part by the National Honey Board, to further determine if something pathogenic could be causing colonies to collapse.

Mr. Hackenberg, the beekeeper, agreed to take his empty bee boxes and other equipment to Food Technology Service, a company in Mulberry, Fla., that uses gamma rays to kill bacteria on medical equipment and some fruits. In early results, the irradiated bee boxes seem to have shown a return to health for colonies repopulated with Australian bees.

"This supports the idea that there is a pathogen there," Dr. Cox-Foster said. "It would be hard to explain the irradiation getting rid of a chemical."

Still, some environmental substances remain suspicious.

Chris Mullin, a Pennsylvania State University professor and insect toxicologist, recently sent a set of samples to a federal laboratory in Raleigh, N.C., that will screen for 117 chemicals. Of greatest interest are the "systemic" chemicals that are able to pass through a plant's circulatory system and move to the new leaves or the flowers, where they would come in contact with bees.

One such group of compounds is called neonicotinoids, commonly used pesticides that are used to treat corn and other seeds against pests. One of the neonicotinoids, imidacloprid, is commonly used in Europe and the United States to treat seeds, to protect residential foundations against termites and to help keep golf courses and home lawns green.

In the late 1990s, French beekeepers reported large losses of their bees and complained about the use of imidacloprid, sold under the brand name Gaucho. The chemical, while not killing the bees outright, was causing them to be disoriented and stay away from their hives, leading them to die of exposure to the cold, French researchers later found. The beekeepers labeled the syndrome "mad bee disease."

The French government banned the pesticide in 1999 for use on sunflowers, and later for corn, despite protests by the German chemical giant Bayer, which has said its internal research showed the pesticide was not toxic to bees. Subsequent studies by independent French researchers have disagreed with Bayer. Alison Chalmers, an eco-toxicologist for Bayer CropScience, said at the meeting today that bee colonies had not recovered in France as beekeepers had expected. "These chemicals are not being used anymore," she said of imidacloprid, "so they certainly were not the only cause."

Among the pesticides being tested in the American bee investigation, the neonicotinoids group "is the number-one suspect," Dr. Mullin said. He hoped results of the toxicology screening will be ready within a month.

Correction: April 26, 2007

An article in Science Times on Tuesday about efforts to solve the mystery of collapsing honeybee populations misstated the institution where a project to sequence honeybee genes was completed late last year. It is Baylor College of Medicine, not Baylor University. (The two became separate institutions in 1969.) And a map with the article, showing the extent of the problem in the United States, reversed the labels for Kansas and Nebraska, two states where collapsing populations have not been reported.

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/24/science/24bees.html?_r=1&oref=slogin

DISAPPEARING BEES! TAIWAN STUNG BY MILLIONS OF MISSING BEES ...

10,000,000 HAVE VANISHED THUS FAR! / WHY AREN'T THEY RETURNING HOME TO

THEIR BEEKEEPERS?! –

Thursday, April 26, 2007, 6:39 a.m. ET

TAIPEI (Reuters) – Taiwan's bee farmers are feeling the sting of lost business and possible crop danger after millions of the honey-making, plant-pollinating insects vanished during volatile weather, media and experts said on Thursday.

Over the past two months, farmers in three parts of Taiwan have reported most of their bees gone, the Chinese-language United Daily News reported. Taiwan's TVBS television station said about 10 million bees had vanished in Taiwan.

A beekeeper on Taiwan's northeastern coast reported 6 million insects missing "for no reason", and one in the south said 80 of his 200 bee boxes had been emptied, the paper said.

Beekeepers usually let their bees out of boxes to pollinate plants and the insects normally make their way back to their owners. However, many of the bees have not returned over the past couple of months.

Possible reasons include disease, pesticide poisoning and unusual weather, varying from less than 20 degrees Celsius (68 degrees Fahrenheit) to more than 30 degrees Celsius over a few days, experts say.

"You can see climate change really clearly these days in Taiwan," said Yang Ping-shih, entomology professor at the National Taiwan University. He added that two kinds of pesticide can make bees turn "stupid" and lose their sense of direction. As affected beekeepers lose business, fruit growers may lack a key pollination source and neighbors might get stung, he said.

Billions of bees have fled hives in the United States since late 2006, instead of helping pollinate $15 billion worth of fruits, nuts and other crops annually. Disappearing bees also have been reported in Europe and Brazil.

The mass buzz-offs are isolated cases so far, a Taiwan government Council of Agriculture official said. But the council may collect data to study the causes of the vanishing bees and gauge possible impacts, said Kao Ching-wen, a pesticides section chief at the council.

"We want to see what the reason is, and we definitely need some evidence," Kao said. "It's hard to say whether there will be an impact."

------------------------------------------

IMPORTANT RESOURCES:

WIKIPEDIA ON COLONY COLLAPSE DISORDER:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Colony_collapse_disorder

MAAREC COLONY COLLAPSE DISORDER WEB SITE:

http://maarec.cas.psu.edu/ColonyCollapseDisorder.html

MAP OF U.S. STATES REPORTING COLONY COLLAPSE DISORDER:

http://maarec.cas.psu.edu/pressReleases/CCDMap07FebRev1-.jpg

THE WAY BACK TO BIOLOGICAL BEEKEEPING (DEE LUSBY):

http://www.beesource.com/pov/lusby/index.htm

GENERAL BEE ARTICLES & REPORTS:

http://www.beesource.com/news/index.htm

ORGANIC & KILLER BEES SEEM RESISTANT TO 'COLONY COLLAPSE DISORDER'

(4/24/2007):http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/12889

HONEY BEE DIE-OFF ALARMS BEEKEEPERS, CROP GROWERS & RESEARCHERS

(4/24/2007):http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/12888

HONEY BEE EXPERTS GATHER TO POOL KNOWLEDGE (4/22/2007):

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/12880

HONEY BEE DIE-OFF RESOURCES (4/17/2007):

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/12857

ARE MOBILE PHONES WIPING OUT OUR BEES? (4/15/2007):

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/12851

BEE COLONIES ACROSS U.S. CONTINUE TO DIE (4/7/2007):

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/12825

ARE GM CROPS KILLING BEES? (3/23/2007):

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/12754

HONEYBEES VANISH, LEAVING KEEPERS IN PERIL (2/27/2007):

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/12647

U.S. BEE COLONIES DECIMATED BY MYSTERIOUS AILMENT (2/14/2007):

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/12588

PARASITE DEVASTATES U.S. BEES (5/2/2005):

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/9104

MAD BEE DISEASE (2/20/2001):

http://groups.yahoo.com/group/nhnenews/message/1181

FACTORY FARMING RESOURCE PAGE:

http://www.nhne.org/tabid/451/Default.aspx

FACTORY FARMING and CRUELTY TO ANIMALS NEWS STORIES:

http://tinyurl.com/hmy5k

------------------------------------------

© Reuters 2007. All Rights Reserved.

http://today.reuters.com/news/articlenews.aspx?type=scienceNews&storyid=2007-04-26T104754Z_01_TP162481_RTRUKOC_0_US-TAIWAN-BEES.xml&src=rss&rpc=22

SCIENCE IN THE NEWS

from Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society

Today's Headlines - April 26, 2007

Experts May Have Found What's Bugging the Bees

from the Los Angeles Times

A fungus that caused widespread loss of bee colonies in Europe and Asia may

be playing a crucial role in the mysterious phenomenon known as Colony

Collapse Disorder that is wiping out bees across the United States, UC San

Francisco researchers said Wednesday.

Researchers have been struggling for months to explain the disorder, and

the new findings provide the first solid evidence pointing to a potential

cause. But the results are "highly preliminary" and are from only a few

hives from Le Grand in Merced County, UCSF biochemist Joe DeRisi said. "We

don't want to give anybody the impression that this thing has been solved."

Other researchers said Wednesday that they too had found the fungus, a

single-celled parasite called Nosema ceranae, in affected hives from around

the country - as well as in some hives where bees had survived. Those

researchers have also found two other fungi and half a dozen viruses in the

dead bees.

To read more: http://www.latimes.com/news/science/la-sci-

bees26apr26,1,7929894.story

Or: http://tinyurl.com/3d5elk

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/24/science/24bees.html

BEES VANISH, AND SCIENTISTS RACE FOR REASONS FOR EMERGING GLOBAL FOOD

CRISIS! / MORE THAN 25% OF AMERICA's 2.4 MILLION BEE COLONIES HAVE BEEN

LOST ... BUT WHY?! –

By Alexei Barrionuevo, New York Times,

Thursday, April 26, 2007

BELTSVILLE, MD. – What is happening to the bees?

More than a quarter of the country's 2.4 million bee colonies have been

lost -- tens of billions of bees, according to an estimate from the

Apiary Inspectors of America, a national group that tracks beekeeping.

So far, no one can say what is causing the bees to become disoriented

and fail to return to their hives.

As with any great mystery, a number of theories have been posed, and

many

seem to researchers to be more science fiction than science. People have

blamed genetically modified crops, cellular phone towers and

high-voltage transmission lines for the disappearances.

Or was it a secret plot by Russia or Osama bin Laden to bring down

American agriculture? Or, as some blogs have asserted, the rapture of

the bees, in which God recalled them to heaven? Researchers have heard

it all.

The volume of theories "is totally mind-boggling," said Diana

Cox-Foster, an entomologist at Pennsylvania State University. With

Jeffrey S. Pettis, an

entomologist from the United States Department of Agriculture, Dr.

Cox-Foster is leading a team of researchers who are trying to find

answers to explain "colony collapse disorder," the name given for the

disappearing bee syndrome.

"Clearly there is an urgency to solve this," Dr. Cox-Foster said. "We

are trying to move as quickly as we can."

Dr. Cox-Foster and fellow scientists who are here at a two-day meeting

to discuss early findings and future plans with government officials

have been focusing on the most likely suspects: a virus, a fungus or a

pesticide.

About 60 researchers from North America sifted the possibilities at the

meeting today. Some expressed concern about the speed at which adult

bees are disappearing from their hives; some colonies have collapsed in

as little as two days. Others noted that countries in Europe, as well as

Guatemala and parts of Brazil, are also struggling for answers.

"There are losses around the world that may or not be linked," Dr.

Pettis

said.

The investigation is now entering a critical phase. The researchers have

collected samples in several states and have begun doing bee autopsies

and genetic analysis.

So far, known enemies of the bee world, like the varroa mite, on their

own at least, do not appear to be responsible for the unusually high

losses.

Genetic testing at Columbia University has revealed the presence of

multiple

micro-organisms in bees from hives or colonies that are in decline,

suggesting that something is weakening their immune system. The

researchers have found some fungi in the affected bees that are found in

humans whose immune systems have been suppressed by the Acquired Immune

Deficiency Syndrome or cancer.

"That is extremely unusual," Dr. Cox-Foster said.

Meanwhile, samples were sent to an Agriculture Department laboratory in

North Carolina this month to screen for 117 chemicals. Particular

suspicion falls on a pesticide that France banned out of concern that it

may have been decimating bee colonies. Concern has also mounted among

public officials.

"There are so many of our crops that require pollinators," said

Representative Dennis Cardoza, a California Democrat whose district

includes that state¹s central agricultural valley, and who presided

last month at a Congressional hearing on the bee issue. "We need an

urgent call to arms to try to ascertain what is really going on here

with the bees, and bring as

much science as we possibly can to bear on the problem."

So far, colony collapse disorder has been found in 27 states, according

to Bee Alert Technology Inc., a company monitoring the problem. A recent

survey of 13 states by the Apiary Inspectors of America showed that 26

percent of beekeepers had lost half of their bee colonies between

September and March.

Honeybees are arguably the insects that are most important to the human

food

chain. They are the principal pollinators of hundreds of fruits,

vegetables, flowers and nuts. The number of bee colonies has been

declining since the 1940s, even as the crops that rely on them, such as

California almonds, have grown.

In October, at about the time that beekeepers were experiencing huge bee

losses, a study by the National Academy of Sciences questioned whether

American agriculture was relying too heavily on one type of pollinator,

the honeybee.

Bee colonies have been under stress in recent years as more beekeepers

have

resorted to crisscrossing the country with 18-wheel trucks full of bees

in search of pollination work. These bees may suffer from a diet that

includes artificial supplements, concoctions akin to energy drinks and

power bars. In several states, suburban sprawl has limited the bees'

natural forage areas.

So far, the researchers have discounted the possibility that poor diet

alone could be responsible for the widespread losses. They have also set

aside for now the possibility that the cause could be bees feeding from

a commonly used genetically modified crop, Bt corn, because the symptoms

typically associated with toxins, such as blood poisoning, are not

showing up in the affected bees.

But researchers emphasized today that feeding supplements produced from

genetically modified crops, such as high-fructose corn syrup, need to be

studied. The scientists say that definitive answers for the colony

collapses could be

months away. But recent advances in biology and genetic sequencing are

speeding the search.

Computers can decipher information from DNA and match pieces of genetic

code

with particular organisms. Luckily, a project to sequence some 11,000

genes

of the honeybee was completed late last year at Baylor College of

Medicine

in Houston, giving scientists a huge head start on identifying any

unknown

pathogens in the bee tissue.

"Otherwise, we would be looking for the needle in the haystack," Dr.

Cox-Foster said.

Large bee losses are not unheard of. They have been reported at several

points in the past century. But researchers think they are dealing with

something new -- or at least with something previously unidentified.

"There could be a number of factors that are weakening the bees or

speeding

up things that shorten their lives," said Dr. W. Steve Sheppard, a

professor

of entomology at Washington State University. "The answer may already be

with us."

Scientists first learned of the bee disappearances in November, when

David

Hackenberg, a Pennsylvania beekeeper, told Dr. Cox-Foster that more than

50

percent of his bee colonies had collapsed in Florida, where he had taken

them for the winter.

Dr. Cox-Foster, a 20-year veteran of studying bees, soon teamed with

Dennis

vanEngelsdorp, the Pennsylvania apiary inspector, to look into the

losses. In December, she approached W. Ian Lipkin, director of the

Greene Infectious

Disease Laboratory at Columbia University, about doing genetic

sequencing of tissue from bees in the colonies that experienced losses.

The laboratory uses a recently developed technique for reading and

amplifying short

sequences of DNA that has revolutionized the science. Dr. Lipkin, who

typically works on human diseases, agreed to do the analysis, despite

not knowing who would ultimately pay for it. His laboratory is known for

its work in finding the West Nile disease in the United States.

Dr. Cox-Foster ultimately sent samples of bee tissue to researchers at

Columbia, to the Agriculture Department laboratory in Maryland, and to

Gene Robinson, an entomologist at the University of Illinois.

Fortuitously, she had frozen bee samples from healthy colonies dating to

2004 to use for comparison.

After receiving the first bee samples from Dr. Cox-Foster on March 6,

Dr. Lipkin¹s team amplified the genetic material and started

sequencing to separate virus, fungus and parasite DNA from bee DNA.

"This is like C.S.I. for agriculture," Dr. Lipkin said. "It is

painstaking,

gumshoe detective work."

Dr. Lipkin sent his first set of results to Dr. Cox-Foster, showing that

several unknown micro-organisms were present in the bees from collapsing

colonies. Meanwhile, Mr. vanEngelsdorp and researchers at the

Agriculture Department lab here began an autopsy of bees from collapsing

colonies in California, Florida, Georgia and Pennsylvania to search for

any known bee pathogens.

At the University of Illinois, using knowledge gained from the

sequencing of

the bee genome, Dr. Robinson¹s team will try to find which genes in

the collapsing colonies are particularly active, perhaps indicating

stress from exposure to a toxin or pathogen. The national research team

also quietly began a parallel study in January, financed in part by the

National Honey Board, to further determine if something pathogenic could

be causing colonies to collapse.

Mr. Hackenberg, the beekeeper, agreed to take his empty bee boxes and

other

equipment to Food Technology Service, a company in Mulberry, Fla., that

uses

gamma rays to kill bacteria on medical equipment and some fruits. In

early results, the irradiated bee boxes seem to have shown a return to

health for

colonies repopulated with Australian bees.

"This supports the idea that there is a pathogen there," Dr. Cox-Foster

said. "It would be hard to explain the irradiation getting rid of a

chemical."

Still, some environmental substances remain suspicious. Chris Mullin, a

Pennsylvania State University professor and insect toxicologist,

recently sent a set of samples to a federal laboratory in

Raleigh, N.C., that will screen for 117 chemicals. Of greatest interest

are

the "systemic" chemicals that are able to pass through a plant¹s

circulatory system and move to the new leaves or the flowers, where they

would come in

contact with bees.

One such group of compounds is called neonicotinoids, commonly used

pesticides that are used to treat corn and other seeds against pests.

One of the neonicotinoids, imidacloprid, is commonly used in Europe and

the United States to treat seeds, to protect residential foundations

against termites and to help keep golf courses and home lawns green.

In the late 1990s, French beekeepers reported large losses of their bees

and

complained about the use of imidacloprid, sold under the brand name

Gaucho. The chemical, while not killing the bees outright, was causing

them to be

disoriented and stay away from their hives, leading them to die of

exposure

to the cold, French researchers later found. The beekeepers labeled the

syndrome "mad bee disease."

The French government banned the pesticide in 1999 for use on

sunflowers,

and later for corn, despite protests by the German chemical giant Bayer,

which has said its internal research showed the pesticide was not toxic

to

bees. Subsequent studies by independent French researchers have

disagreed

with Bayer.

Alison Chalmers, an eco-toxicologist for Bayer CropScience, said at the

meeting today that bee colonies had not recovered in France as

beekeepers had expected. "These chemicals are not being used anymore,"

she said of imidacloprid, "so they certainly were not the only cause."

Among the pesticides being tested in the American bee investigation, the

neonicotinoids group "is the number-one suspect," Dr. Mullin said. He

hoped results of the toxicology screening will be ready within a month.

CORRECTION: April 26, 2007

An article in Science Times on Tuesday about efforts to solve the

mystery of

collapsing honeybee populations misstated the institution where a

project to sequence honeybee genes was completed late last year. It is

Baylor College of Medicine, not Baylor University. (The two became

separate institutions in 1969.)

And a map with the article, showing the extent of the problem in the

United States, reversed the labels for Kansas and Nebraska, two states

where collapsing populations have not been reported.

© 2007 The New York Tmes Company / Click below for "Printer Friendly

Version."

http://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/24/science/24bees.html?_r=1&oref=slogin&pagewanted=print

The great bee mystery; Ontario honeybees are dying off by the millions -

and no one knows why

Colin McKim / The Packet & Times

Local News - Wednesday, April 25, 2007 @ 09:00

Severn Township beekeeper Tom Morrisey lost one-third of his bee colonies this winter. In some parts of the province, beekeeping operations have been completely wiped out.

Photo: Submitted

|

Ontario's beekeepers, stung by alarming colony losses this winter, are asking the province to help them rebuild their businesses and investigate the causes of the massive die-offs.

"It's very disconcerting," said Severn Township beekeeper Tom Morrisey, who lost about one-third of his honeybees this winter.

"They don't know what's causing it - that's the troubling part."

Beekeepers in the Orillia area have fared better than other parts of the province, where some honey producers lost all of their bees.

The north shore of Lake Erie, including the fruit belt, where bees are critical to the pollination of orchards, has been hit the hardest, with losses between 50 and 100 per cent, said Morrisey.

He added it's been standard practice for years to truck colonies of domesticated bees to farms, where their activity can increase yields fivefold. The pollination value in Ontario has been estimated at $171 million.

"It has such a big impact on agriculture. People are just frantic." A frightening phenomenon called colony collapse disorder (CCD) has recently been devastating bee colonies in the United States.

"For years, we've been immune," said Morrisey.

At this point, the Ontario Beekeepers Association (OBA) has not made a direct connection to problems south of the border, where parasites, pesticides, excessive transportation of colonies and weather are all suspected of contributing to CCD.

The factors causing the Ontario die-offs may be quite different, said Morrisey, an OBA director.

He said the culprit here may be the weather, particularly the long, mild fall followed by a sudden and harsh freeze-up.

Bees are cold-blooded and stay warm by clustering together through the cold months.

Normally, a dormant period precedes the onset of winter as bees gradually adjust to the falling temperatures, said Morrisey.

"This year, all of a sudden, bang, it was deep and cold for a long time."

Area beekeeper Paul Gillett, who lost 12 of 50 hives, said he thinks the bees didn't store adequate honey in the fall.

The worker bees form a cluster around the queen, keeping her warm so she can lay eggs in the spring and repopulate the hive, said Gillett.

"If the queen dies, the hive dies."

The OBA directors decided Monday to ask the Ministry of Agriculture to fund field analysis of the colony deaths and to help beekeepers rebuild their bee colonies.

Morrisey said he will be able to rebound from a 30 per cent loss of his bees.

But beekeepers with higher losses will need financial help, he said: "You can't get a bank loan for bees."

– 1 of 2 –

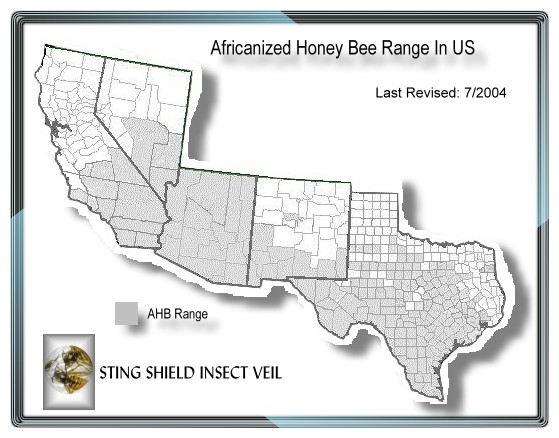

'KILLER BEES' SEEM RESISTANT TO "COLONY COLLAPSE DISORDER!" –

By Dan Sorenson, Arizona Daily Star

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

http://www.azstarnet.com/allheadlines/176000

TUCSON, ARIZONA – Although experts are stumped about what's causing

the

colony-collapse disorder die-off in U.S. commercial beehives, there is

some

speculation that Arizona's famed Africanized -- or "killer bee" --

wild-bee

population is somehow immune.

------------------------------------------

– 2 of 2 –

HONEY BEE DIE-OFF ALARMS BEEKEEPERS, CROP GROWERS AND RESEARCHERS! –

Science Daily / Penn State: College Of Agricultural Sciences, Tuesday,

April 24, 2007

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/04/070422190612.htm

An alarming die-off of honey bees has beekeepers fighting for commercial

survival and crop growers wondering whether bees will be available to

pollinate their crops this spring and summer. Researchers are scrambling

to

find answers to what's causing an affliction recently named Colony

Collapse

Disorder, which has decimated commercial beekeeping operations in

Pennsylvania and across the country.

"During the last three months of 2006, we began to receive reports from

commercial beekeepers of an alarming number of honey bee colonies dying

in the eastern United States," says Maryann Frazier, apiculture

extension associate in Penn State's College of Agricultural Sciences.

"Since the beginning of the year, beekeepers from all over the country

have been reporting unprecedented losses. This has become a highly

significant yet poorly understood problem that

threatens the pollination industry and the production of commercial

honey in

the United States," she says. "Because the number of managed honey bee

colonies is less than half of what it was 25 years ago, states such as

Pennsylvania can ill afford these heavy losses."

A working group of university faculty researchers, state regulatory

officials, cooperative extension educators and industry representatives

is working to identify the cause or causes of Colony Collapse Disorder

and to develop management strategies and recommendations for beekeepers.

Participating organizations include Penn State, the U.S. Department of

Agriculture, the agriculture departments in Pennsylvania and Florida,

and Bee Alert Technology Inc., a technology transfer company affiliated

with the University of Montana.

"Preliminary work has identified several likely factors that could be

causing or contributing to CCD," says Dennis vanEngelsdorp, acting state

apiarist with the Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture. "Among them

are mites and associated diseases, some unknown pathogenic disease and

pesticide

contamination or poisoning."

Initial studies of dying colonies revealed a large number of disease

organisms present, with no one disease being identified as the culprit,

vanEngelsdorp explains. Ongoing case studies and surveys of beekeepers

experiencing CCD have found a few common management factors, but no

common environmental agents or chemicals have been identified.

The beekeeping industry has been quick to respond to the crisis. The

National Honey Board has pledged $13,000 of emergency funding to the CCD

working group. Other organizations, such as the Florida State Beekeepers

Association, are working with their membership to commit additional

funds. This latest loss of colonies could seriously affect the

production of several important crops that rely on pollination services

provided by commercial beekeepers.

"For instance, the state's $45 million apple crop -- the fourth largest

in the country -- is completely dependent on insects for pollination,

and 90 percent of that pollination comes from honey bees," Frazier says.

"So the value of honey bee pollination to apples is about $40 million."

In total, honey bee pollination contributes about $55 million to the

value of crops in the state. Besides apples, crops that depend at least

in part on honey bee pollination include peaches, soybeans, pears,

pumpkins, cucumbers, cherries, raspberries, blackberries and

strawberries.

Frazier says to cope with a potential shortage of pollination services,

growers should plan well ahead. "If growers have an existing contract or

relationship with a beekeeper, they should contact that beekeeper as

soon as

possible to ascertain if the colonies they are counting on will be

available," she advises.

"If growers do not have an existing arrangement with a beekeeper but are

counting on the availability of honey bees in spring, they should not

delay but make contact with a beekeeper and arrange for pollination

services now.

"However, beekeepers overwintering in the north many not know the status

of

their colonies until they are able to make early spring inspections,"

she adds. "This should occur in late February or early March but is

dependent on weather conditions. Regardless, there is little doubt that

honey bees are going to be in short supply this spring and possibly into

the summer."

A detailed, up-to-date report on Colony Collapse Disorder can be found

on

the Mid-Atlantic Apiculture Research and Extension Consortium Web site

at:

http://maarec.org/

------------------------------------------

© 2007 Science Daily.com

http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2007/04/070422190612.htm

SCIENCE IN THE NEWS

from Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Society

Today's Headlines - April 26, 2007

Experts May Have Found What's Bugging the Bees

from the Los Angeles Times (Registration Required)

A fungus that caused widespread loss of bee colonies in Europe and Asia may

be playing a crucial role in the mysterious phenomenon known as Colony

Collapse Disorder that is wiping out bees across the United States, UC San

Francisco researchers said Wednesday.

Researchers have been struggling for months to explain the disorder, and

the new findings provide the first solid evidence pointing to a potential

cause. But the results are "highly preliminary" and are from only a few

hives from Le Grand in Merced County, UCSF biochemist Joe DeRisi said. "We

don't want to give anybody the impression that this thing has been solved."

Other researchers said Wednesday that they too had found the fungus, a

single-celled parasite called Nosema ceranae, in affected hives from around

the country - as well as in some hives where bees had survived. Those

researchers have also found two other fungi and half a dozen viruses in the

dead bees.

To read more: http://www.latimes.com/news/science/la-sci-

bees26apr26,1,7929894.story

Or: http://tinyurl.com/3d5elk

"Analysis of the dissected bees turned up weakened immune systems and an alarmingly high number of foreign fungi, bacteria and other organisms"

http://www.cbc.ca/technology/story/2007/02/12/bee-deaths.html

That link to the story about several honeybee colony deaths was surprising because they actually mentioned "fungus and other organisms" , the "other" just might be MYCOPLASMA.

Mycoplasma is that common-chemtrail component, but it is also common problem for labs and contamination - it seems to be everywhere. Naturally or man made is the question, and there is lots of evidence that man-made mycoplasma is in chemtrails.

Chemtrails, or other distribution methods, just might be what is killing these bee colonies.

Hmmm, just a thought [I have several each day, ha ha ha].

Karlin

__._,_.___

|

The Bees Are Not Just Dying,

They're Freaking Out, Killing Animals, Swarming Wildly

|

Quote |

A cursory search has resulted in 4 bee swarm attacks in the last

24 hours... and many more in the last week or so...

Bees swarm the John Ball Zoo in Grand Rapids

[link

to www.wzzm13.com]

WZZM, MI -

Created: 5/15/2007

Grand Rapids - A swarm of bees decided to

set up shop inside the John Ball Zoo Tuesday

afternoon.

The bees were clumped around a Maple Tree

near the central part of the zoo.

A Zoo keeper noticed the bees buzzing this

afternoon and called in a bee keeper. He

sprayed them with sugar water causing them

to fall to the ground. The bee keeper

captured the queen bee and put her inside

another hive causing the rest of the bees to

follow her.

No one was stung by the bees.

In Napa, shelter for the swarm

[link

to www.napavalleyregister.com]

Napa Valley Register, CA

In Napa, shelter for the

swarm

By THOMAS S. KALBRENER

Tuesday, May 15, 2007

Two Thursdays ago, we came

home mid-afternoon to find

honey bees swarming in the

camellia bushes at the front

of our house. I was

concerned, because I have

had an allergic reaction to

wasp stings. We watched for

about half an hour, and then

I called the county Ag

Department.

They gave me a list of

beekeepers to call. Bees are

in short and decreasing

supply here in California,

suffering from a still vague

plague that has decimated

swarms necessary to

pollinate virtually

everything here. I wanted to

see if these bees could be

gathered. The third call on

the list got me to Rob

Keller, a local beekeeper

and instructor in

beekeeping. Rob was here in

about half an hour, sorry

that the bees, swarming when

I called, had taken up in a

hole in the front of our

house. The hole was the

result of undone work

performed by whoever

insulated this old house 25

years ago. Because the

bushes hide the front of the

house to about seven feet,

we had never noticed the

hole. The bees found it.

Rob was not optimistic about

recovering the swarm.

Nevertheless, he fashioned a

screen funnel with duct tape

and window screen and fixed

it over the hole on the

premise that bees leaving

could not return. His hope

was that they would swarm in

the bushes and he could

recover them in a few hours.

Partly successful, the

apparatus did keep some bees

out. He next hung a "hive"

in the bushes baited with a

honeycomb. This hive

resembled nothing so much as

a file box with small

bee-sized holes in both

ends. The intention here was

to bait the worker bees into

comb-building in the box

instead of our wall.

Each day, he has checked the

hive potential but could

still see the queen through

the house hole. That

Saturday, to encourage her

evacuation of the house, he

introduced a smelly manure

substance in the hole. It

did not drive out the queen,

but we are in consideration

of leaving. We are patient,

because saving a swarm of

bees is a good thing and Rob

is sincere and diligent

about recovering the swarm.

If he cannot recover the

queen, he will need to take

whatever bees he can recover

and introduce them to

another needy queen in

another hive. We would have

to do away with the queen

and plug the hole.

About 5:15 p.m. the next

Tuesday, Rob showed up to

check the hive development.

Not sure how or when, but

the queen had left the wall

and migrated to the box

hive. She has whipped the

worker bees into building a

comb on the inside cover of

the box. I think her plan is

to plant more little bees in

the comb, for starters. Last

week, in the cool night air,

Rob removed the hive box,

and we are bee free. I will

have to seal up the holes in

the house to be sure we

don't attract another swarm

or any holdover bees that

were not on the platform

when the bee train left. We

are delighted that Rob got a

complete swarm. He will keep

this swarm for probably a

year to assure its health

and then give it to a

student. Wonderful news for

the bees, Rob, his lucky

student, flowers everywhere

and us.

Thanks to the Napa County Ag

Department and a bunch of

local beekeepers this swarm

was saved.

(Kalbrener lives in Napa.)

Africanized bees kill three dogs

[link

to www.hesperiastar.com]

Hesperia Star, CA -

Africanized bees kill three dogs

By BEAU

YARBROUGH Staff Writer

May 14, 2007 -

Africanized bees swarmed and killed three dogs last

week, including a 100-pound female mastiff.

Africanized bees swarmed and killed three dogs last

week, including a 100-pound female mastiff.

The bees, also known as "killer bees," are hybrids of

the African honeybee and more docile European breeds.

On Monday, May 7, a hive of Africanized bees killed

three mastiffs at a Hesperia residence near the

intersection of Pinon Avenue and Manzanita Street,

just two blocks south of Bear Valley Road.

"The female [mastiff], she was well over 100 pounds,"

Hesperia Animal Control Supervisor Tony Genovesi said

Monday. A 90-pound male dog and a 20-pound puppy were

also swarmed and killed. The dogs' owner was also

stung several times trying to save them, according to

a release issued by the city on Tuesday.

San Bernardino County Vector Control identified the

bees as Africanized honeybees.

"The difference with people versus animals,

obviously, is that these animals were chained and

didn't have the chance to run away," Genovese said.

"Even if they were in a yard, there obviously may not

be enough room to run away, because the key is to get

as much distance between you and the hive."

The hive of Africanized bees was located in a hollow

stucco wall of a home.

"Apparently, a branch from a tree branch broke and

fell right where the hive is, and that's what was

stirring them up," Genovesi said. "This is the first

[swarm] that I've heard of that's actually killed

animals like this, but I know we've dealt with other