NATIVE AMERICAN HOUSING

collected by Dee Finney

This page is for students for school projects.

If you need more information or a different tribe than listed below,

e-mail Dee777@aol.com and

I will attempt to locate what you need

BUILDING A STURDY TIPI / TEPEE/ TEEPEE

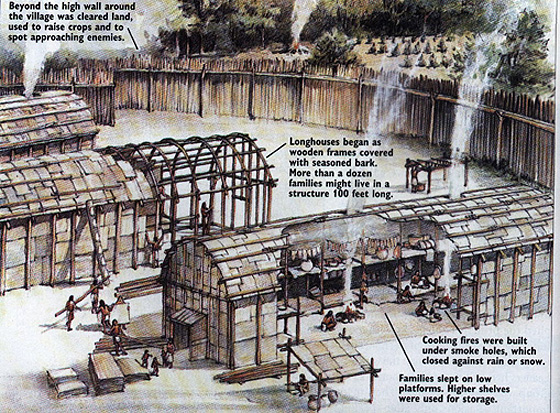

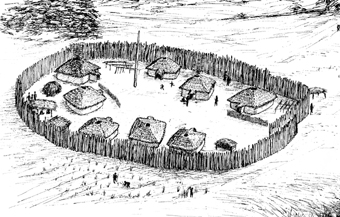

NATIVE HOUSING In and north of the United States there were some twenty well-defined types of native dwellings, varying from the mere brush shelter to the five-storied pueblo. In the eastern United States and adjacent parts of Canada the prevailing type was that commonly known under the Algonkian name of wigwam, of wagon-top shape, with perpendicular sides and ends and rounded roof, and constructed of stout poles set in the ground and covered with bark or with mats woven of grass or rushes. Doorways at each end served also as windows, and openings in the roof allowed the smoke to escape. Not even pueblo architecture had evolved a chimney. In general the houses were communal, several closely related families occupying the same dwelling. The Iroquois houses were sometimes one hundred feet in length, divided into compartments about ten feet square, opening upon a central passageway along which were ranged the fires, two families occupying opposite compartments at the same fire. Raised platforms around the sides of the room were covered with skins and served both as seats and beds. The houses of a settlement were usually scattered irregularly, according to the convenience of the owner, but in some cases, especially on disputed tribal frontiers, they were set compactly together in regular streets, and surrounded by strong stockades. The Iroquois stockaded forts had platforms running around on the inside, near the top, from which the defenders could more easily shoot down upon the enemy. In the Gulf states, every important settlement had its "town-house", a great circular structure, with conical roof, built of logs, and devoted to councils and tribal ceremonials. The tipi (the Sioux name for house) or conical tent-dwelling of the upper lake and plains region was of poles set lightly in the ground, bound together near the top, and covered with bark or mats in the lake country, and with dressed buffalo skins on the plains. It was easily portable, and two women could set it up or take in down within an hour. On ceremonial occasions the tipi camp was arranged in a great circle, with the ceremonial "medicine lodge" in the centre. The semi-sedentary Pawnee Mandan, and other tribes along the Missouri built solid circular structures of logs, covered with earth, capable sometimes of housing a dozen families. The Wichita and other tribes of the Texas border built large circular houses of grass thatch laid over a framework of poles. The Navaho hogan, was a smaller counterpart of the Pawnee "earth lodge". The communal pueblo structure of the Rio Grande region consisted of a number—sometimes hundreds—of square-built rooms of various sizes, of stone or adobe laid in clay mortar, with flat roof, court-yards, and intricate passage ways, suggestive of oriental things. The Piute wikiup of Nevada was only one degree above the brush shelter of the Apache. California, with its long stretch from north to south, and its extremes from warm plain to snowclad sierra, had a variety of types, including the semi-subterranean. Along the whole north-west coast, from the Columbia to the Eskimo border, the prevailing type was the rectangular board structure, painted with symbolic designs, and with the great totem pole carved with the heraldic crests of the owner, towering above the doorway. On the Yukon we find the subterranean dwelling, while the Eskimo had both the subterranean house and the dome-shaped iglu, built of blocks of hardened snow. Besides the regular dwellings, almost every tribe had some style of temporary structure, besides "sweat houses", summer arbors, provision caches, etc. |

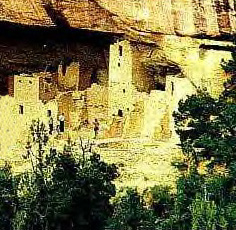

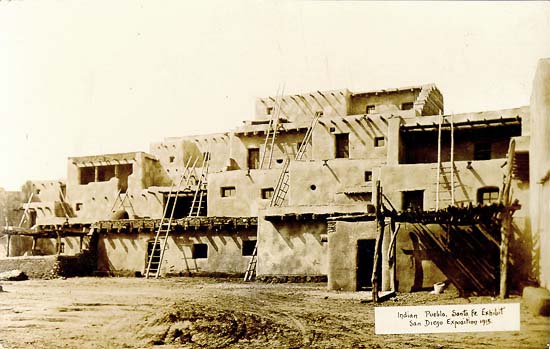

ANASAZI ADOBE HOUSING

LARGE PHOTO - MESA VERDE, COLORADO

|

|

|

Longhouse shell |

Longhouse covered |

Wickiup |

The Accohannock Indian

Tribe

Living Village on Maryland's Eastern Shore

BELLA COOLA DWELLING

Now called Nuxalk (Nu-caulk

This photo is from 1881

(this photo courtesy of Alica Leppamen

Leciurer Instructor

Specializing in Native American Art

|

|

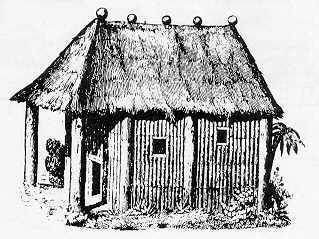

| Cherokee Hut |

Cherokee

7-sided Council Houses

and ceremonies of the moon

* They were an agrarian people who lived in log homes (not tee pees) and observed sacred religious practices. When de Soto first encountered the Cherokee in 1540 he found a unified, peaceful nation of people grouped into about 200 settlements or towns. The nation was composed of a confederacy of red and white towns, otherwise known as war and peace towns. The chiefs of the red towns were subordinated to a supreme war chief of the entire tribe, while the officials of the white towns were under the supreme peace chief of the tribe. The white towns were regarded as places of sanctuary where those who fled from blood avengers might find asylum.

* They lived in about 200 fairly large villages. A normal Cherokee town had about 30 - 60 houses and a large meeting building. Cherokee homes were usually wattle and daub. Wattle is twigs, branches, and stalks woven together to make a frame for a building. Daub is a sticky substance like mud or clay. The Cherokee covered the wattle frame with daub. This created the look of an upside down basket. Later, log cabins with bark roofs were used for homes. The Cheokee villages also had fences around them to prevent enemies from entering.

* Homes were wooden frames covered with woven vines and saplings plastered with mud. These were replaced in later years with log structures. Each village had a council house where ceremonies and tribal meetings were held. The council house was seven-sided to represent the seven clans of the Cherokee: Bird, Paint, Deer, Wolf, Blue, Long Hair, and Wild Potato.

EARTH LODGE

http://www.kstrom.net/isk/maps/houses/hidatsa.html

|

CHEYENNE

Traditional clothing and diet once depended heavily upon the buffalo, but now contain elements of American/European influence. Though they still wear the buckskin garments of their people, many Cheyenne have begun to make use of the cloth textures that the whites have brought from the east. Buffalo hides are also used for their traditional dwelling, the three-poled tipi. These dwellings are highly adaptable to the weather, being rain-proof and surprisingly warm during colder seasons.

Model of traditional Chickasaw dwelling with grass thatched roof

| Native American life in the Mid-South from early explorers. Each of the Mississippian period towns, like Chucalissa, was arranged in a common pattern. In the center was a large open area or plaza, which was a focal point for games and ceremonies, a gathering place for gossip, and a gathering place to take part in trade. | ||||||||||||

|

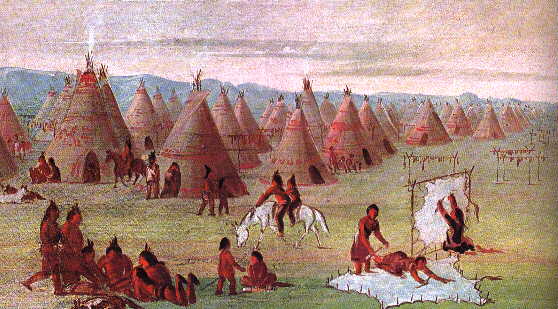

A Comanche camp in 1834 by George Catlin

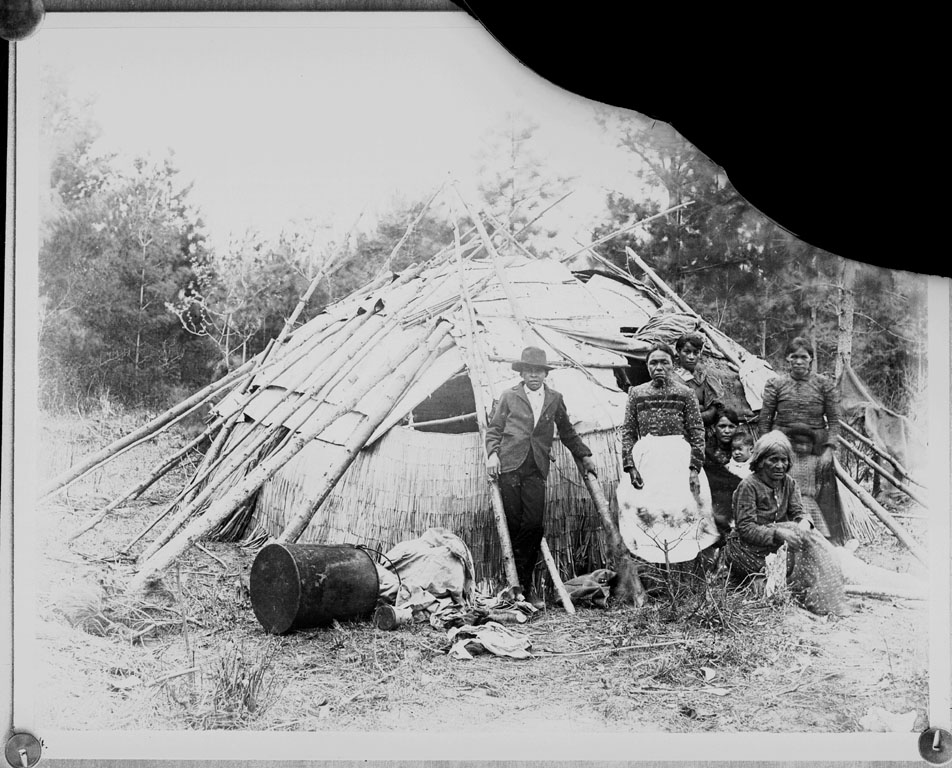

Choctaw

The word for a Choctaw dwelling is 'chukka'

They lived in mud-and-bark cabins with thatched roofs.

The Choctaw Indians cabins were also made from

mud, cane, and straw.

Dwelling description: The Choctaw Indian, dwelling with his family, in a wigwam of a most primitive construction. It was in the form of a bee-hive, or rather of a very high dome. The covering was made of a long, tough grass, that grows near the sea, and the texture was fine and even beautiful. A post in the center supported the fabric, which was shaped by delicate curving poles. A hole in the top admitted the light, and allowed the smoke to pass out; and the fire was near enough to the upright post to permit a kettle to be suspended from one of its knots (or cut branches) near enough to feel the influence of the heat. The door was a covering of mats, and the furniture consisted of a few rude chairs, baskets, and a bed, that was neither savage, nor yet such as marks the civilized man. The attire of the family was partly that of the one condition, and partly that of the other. The man himself was a full-blooded Indian, but his manner had that species of sullen deportment that betrays the disposition without the boldness of the savage. He complained that " basket stuff" was getting scarce, and spoke of an intention of removing his wigwam shortly to some other estate.

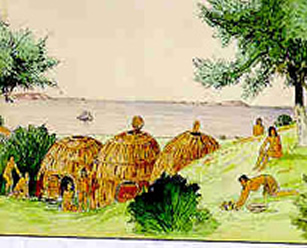

CHUMASH

A Tule Hut

While there were many different Indians in California at the time of the missions; the Chumash were the most widespread. They numbered in the tens of thousands and their territory spread from present-day Malibu to present-day southern Monterey County. To the east they extended all the way to the Carrizo Plain of present-day Kern County. To the west, the Chumash territory spread to the coast and further, out to the Channel Islands, west of today's Santa Barbara. Their land comprised 7,000+ square miles.

They were very important because you could not travel far north/south in California without encountering their territory, and they were a highly intelligent and developed peoples; both prosperous and peaceful. Padre Palˇu wrote that the area was "so densely populated with heathen that right on the road, which runs close along the shore, there are twenty-one large towns, and it is necessary to pass through them in the middle of some and on the edge of others and past others about a gunshot off."

CLATSOP FORT

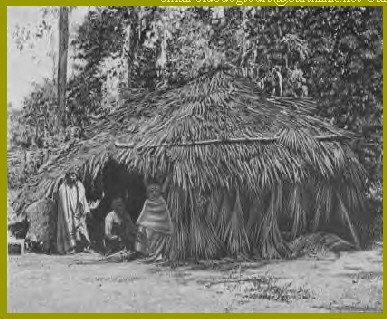

COUSHATTA

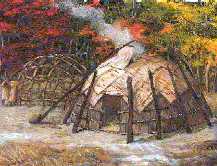

WICKUP

CREEKS

| Creek families lived in dwellings that

consisted of one to four buildings, depending on the size and wealth of the

family. Structures were rectangular and framed with sturdy poles. The walls

were plastered with mud and straw. The roofs were of cypress-bark shingles.

Generally, one structure was the cooking area and winter quarters, one was

the summer lodge, another acted as a granary, and others served other functions.

Near each dwelling the Creeks planted a small private garden where the women

of the family grew corn, beans, tobacco, and other crops. Outside the town

a larger plot of land was used for the communal field in which the main food

supply was grown. Each family possessed its own plot in the common field,

but the entire tribe worked the land together, starting at one end and finishing

at the other. When the time arrived, each family harvested its own plot and

stored the produce in a private granary. Surplus crops could be donated to

the public store, which was used to feed visitors, supply war parties, or

help feed families whose supplies failed. Corn, beans, squash, pumpkins,

and melons were grown in abundance. The Lower Creeks also grew rice. Hickory

nuts and acorns were a source of sustenance. Hunting deer and bear and fishing

also supplemented the food supplies. Each town had its own hunting range,

and the Creeks were careful not to trespass on other towns' preserves. Each

town council carefully regulated hunting to prevent the depletion of game

animals.

European influence extended

beyond what could be found inside the Indians' homes and affected the

structures themselves. By the mid-1700's, the custom of building separate

houses for warm and cool weather began to decline, and various Cherokees

erected only one rectangular dwelling for year-round use. In some places,

though, dual housing persisted until the end of the century. The Cherokee

also ceased building walls of upright posts arranged side by side, and

instead, by the 1780's, copied the European method of placing logs

horizontally. They also adopted fireplaces and wooden floors, and stopped

using woven mats to cover floors

|

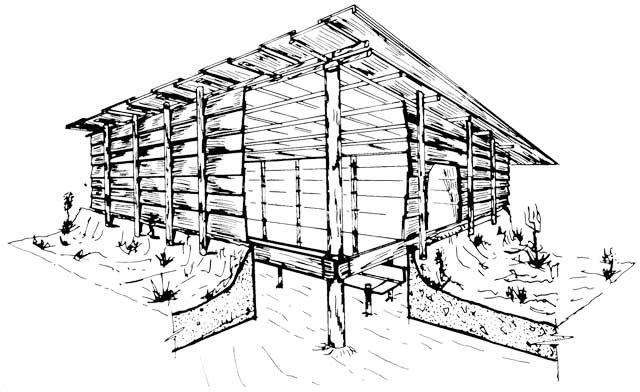

FLATHEAD - CHINOOK

Model

of plank house Model

of plank house

Interior of Plank house |

|

|

The Chinookan people built large cedar plank houses. The cedar plankhouse was the typical permanent dwelling of the Chinookan and other coastal Northwest people. The size of these sturdy buildings ranged from approximately 14 x 20 feet to 40 x 100 feet. The size of the structure depended on the wealth of the owner and the number of families inhabiting it. Each family occupied a distinct portion of the house. Rush mats hanging from the rafters formed the walls to separate the living spaces. At the center of the house was the communal fireplace, where all of the members of the house could gather to socialize, eat, and work during long winter evenings. Sleeping platforms were set up along the walls, and food hung from the rafters to dry.

|

Summer tipi "In the early spring they repaired to the fisheries in the larger river, and fishing, hunting, and root digging continued until midsummer, when they moved into the mountains to gather berries. As autumn approached they returned to the valleys for the late fishing, which continued until cold weather forced them into winter quarters. In the summer, the tipi form of dwelling was used. The permanent winter lodge was of somewhat similar construction, but the ground-plan was a much-flattened ellipse, and the walls were banked with earth to a height of about three feet." |

HOGAN

http://www.kstrom.net/isk/maps/houses/hogan.html

HAVASUPAI BRUSH DWELLING

Havasupai brush dwelling photographed by Edward Curtis.

(Courtesy Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University.

[#ZZc12 907cua])

HOPI

The Huron longhouse was usually made from white birch or alder trees that were small enough to bend, rope that had been made by braiding together thin strips of bark, and sheets of bark to cover the frame.

Huron longhouses were quite similar to Haida houses in length and width. They also averaged between 25 and 33 meters long and could be up to 17 meters wide. Longhouses are almost rectangular, but are more rounded at the ends. The roof can be arched or pitched.

To build a longhouse, the Huron needed a lot of trees. They burned them at the bottom. They would pack wet mud around the tree trunk about a meter off the ground. Then they would pile sticks around the base of the tree trunk and light them on fire. They would let the tree trunk burn until they could push the tree over or until it fell on its own. They might have used a stone chopping tool depending on the size of the tree to make it fall. Remember, longhouses like the one shown here, were built before the Europeans came, before they had metal tools. Once the Huron had the trees they needed, they placed the trees into holes in the ground and tied them at the top in an arch. Bark was stripped off bigger trees in sheets and stacked on the ground. Rocks were put on top of the stack of bark to make it dry flat. Once the bark was dry, it was placed over the frame of the longhouse and tied down. Inside the longhouse, platforms were made and tied on to the walls. These were used for sitting or sleeping.

Some Huron longhouses had holes cut in the top of the roof, which were also covered with either bark or hides to protect the inside from the rain or snow. Although similar to the Haida house, the longhouse did not need a smoke hole because there were enough small openings between the poles to let the smoke out.

there was nothing elaborate about the doorway of a Huron longhouse. They were rectangular frames that were covered by a sheet of bark or an animal hide

The Huron slept on platforms made from the same trees as the house. The Huron slept on platforms made from the same trees as the house. You can see examples of sleeping platforms in the pictures of the model. Compartments or dividers were put up so each family's sleeping and living quarters were more private. Fur, hides, reed mats and sheets of bark were all materials that were used to cover the platforms to make them more comfortable and warm. Compartments or dividers were put up so each family's sleeping and living quarters were more private. Fur, hides, reed mats and sheets of bark were all materials that were used to cover the platforms to make them more comfortable and warm.

Longhouses had many fires. One fire was shared between two families. Some longhouses had up to six fires. Each family did their own cooking on their fire.

Huron longhouses could be found in the areas around the St. Lawrence River and the Great Lakes, particularly Lake Huron. This area is called the Eastern Woodlands region of Canada. The Huron built their longhouses as year round dwellings. They had to be on good soil so that they could plant their crops. They also had to be in an area close to a secondary growth forest, a forest with young trees, so they had enough of the right size trees to build the houses. They were usually close to a water source like the St. Lawrence River or Lake Huron.

The Huron would stay in the same place until the soil used to grow their crops began to be depleted. Then they would move their fields to new areas. Sometimes they would move the whole village.

MORE PHOTOS AND INFO ABOUT HAIDA AND IGLOOS AS WELL

Igloo -- the Traditional Arctic Snow Dome

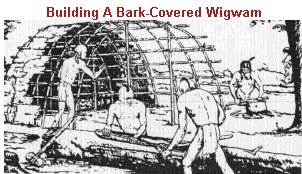

The Iroquois Indians lived in wigwams and longhouses. Wigwams were made by bending young trees to form the round shape of the home. Over this shape pieces of tree bark were overlapped to protect the Indians from bad weather. Over the bark a layer of thatch, or dried grass, was added. A small hole from the top allowed smoke from the fires to escape. Beds were matting covered with animal skin. The Iroquois built log walls all around their villages. The wall had only one opening. They could quickly close this opening if their enemies came near.

Jatibonicu Taino Tribal Council Longhouse

|

Lumbee Village Prior to Modernization |

| Tobacco Barn Model of a tobacco barn common throughout eastern North Carolina for more than 150 years. |

Miami

Principal Dwelling Type: Domed bark, thatch or hide house

... The Piankashaws

were thought to be part of the Miami tribe at one time. ...

www.twingroves.district96.k12.il.us/

NativeAmericans/Miami.html

|

|

|

|

Used by families every day From: |

Miwok Sweat Lodge |

Painting of Cliff House - Mancos Canyon, Colorado

|

|

Mound Example |

Mound Example |

|

|

Village Example |

Construction Example |

* These prehistoric Native Americans, who are called Mississippian Indians by archaeologists, lived in permanent towns which were built on a fairly standard pattern. Ceremonial buildings on large four sided flat-topped mounds faced a plaza. The villagers gathered in the plaza for important events, ceremonies, and to watch various games such as stickball and chunkey. The earthen mounds were built over a period of years. Perhaps they began as a slight rise with an important building on it. After a time, the building burned. Maybe the people set it on fire because it had become infested with vermin or perhaps the grass roof caught fire accidently. Whatever the cause of the fire, the people brought basketful after basketful of dirt to make a mound. When they were satisfied, they built a new building on top. Archeologists do not know what purpose these buildings fulfilled. The most widely accepted ideas are that these buildings were either religious structures, or the homes of chiefs or other important families.

* Mound builders were Indians who built large mounds, or hills, or earth. There were two types of mounds, flat-topped and conical. Flat-topped mounds were flat on the top. These mounds were used as the base for temples or chief's homes. Conical mounds were rounded on the top like a steep hill. These mounds are believed to be where the Mound Builders buried important people. These mounds were built entirely by workers who carried loads of earth on their backs. They had no horses or oxen or other forms of transportation to use for help. Many of these mounds have several hundred tons of dirt, stone, and other materials.

MOUND

BUILDING

Scroll down to lower portion of page

NATCHEZ DWELLING

The Natchez lived comfortably in well-built houses around which peach trees were often planted for fruit and shade. The straw hut at the right is a reconstruction of a Natchez dwelling, Women wore white dresses woven of nettle and mulberry-bark fibers, and the dresses covered them from neck to foot. The men wore deerskin leather jackets and breechcloths and leggings.

NEZ PERCE HOUSING

DWELLINGS: Houses were mat-covered lodges of the tipi form, or more commonly a development of this type in which material of several or many of these circular lodges were used to build a lodge, wedge-shaped communal structure.

See also: Flathead above.

OJIBWE BARK LODGE - 1880

* Keekwillie house or Quiggly house - the native pit-house lodge of the Interior and Plateau peoples; Keewulllie or Quiggly were also used without the "house" ending, particularly by English-speakers

* Nelson (1969) in his Salish-expansion theory asserts that the ancestral Salish brought intensive fishing with them and helped produce the Plateau winter village settlement pattern. He says the Salish expansion originated in the Fraser delta about 4500 B.P. at the end of the Altithermal (Elmendorf 1965). Ames and Marshall (1981) dispute this theory, arguing that pit-house villages first appear by 5000 B.P. in the southeastern part of the Plateau, far from the center of Salish expansion. Somewhat unconvincingly, they ascribe this new residential pattern not to improved fishing techniques imported from the coast, but to an increased intensity of root collection which emphasized a preexisting Plateau subsistence focus.

PIT HOUSE

This is one of the oldest Native American building types. It uses earth berming; this will result in houses cooler in summer and warmer in winter. Above grade (meaning above the ground) a framework of wood poles would support mats and a sod roof. Only in recent years has the modern world rediscovered this concept of literally building with the Earth. It works. And a skilled designer can integrate this technique perfectly with passive solar strategies. The Solar Hemicycle House in Wisconsin is probably the single best example, although many buildings reflect the good common sense of building with the land.

* http://www.bhi-erc.com/map/sec2.htm

There have been 283 archaeological sites found at the Hanford Site. Archaeological sites common to the Hanford Site include the remains of numerous pit house villages, various types of open campsites, cemeteries, hunting camps, and game drive complexes adjacent to the river corridor; quarries and spirit quest monuments on mountains and rocky bluffs; hunting/kill sites in lowland stabilized dunes; and small temporary camps near perennial sources of water located away from the river.

* Northwest Coast houses shared a few significant traits. All were rectangular in floor plan with plank walls and plank roof, and all but those of northwestern California were large structures designed for multifamily use. At the northern and southern extremes of the area deep central pits were dug within the house. In the north, houses were built on a nearly square plan--averaging about 50 feet wide by 55 feet long--and had gabled roofs; walls and framework were intermeshed to form a permanent structural unit. In the Wakashan province, on the other hand, the houses were rectangular--40 feet by 60 to 100 feet. Huge cedar posts with side beams and ridgepoles comprised the permanent framework, and to these were attached wall planks and roof planks that could be taken down, loaded onto canoes, and transported from one site to another. Some Coast Salish similarly built houses of permanent frameworks with detachable siding and roofing; their houses, however, had "shed-roofs," that is, a roof with only one slope instead of the two of the Wakashan house. Some Coast Salish houses were tremendously long, housing many people. Along the lower Columbia the typical house had a deep large rectangular pit, lined with planks, capped with a gabled roof. Only roof and gable ends showed above ground. The northwestern California house type was designed for single family only. Each house had low side walls of redwood planks and a three-pitch roof. Living space was the plank-lined central pit. Northwestern California also added a specialized structure: the men's combined clubhouse and sweat house, a common native Californian institution.

* Sometimes campers in the Great Basin would throw together a windbreak of sagebrush. At times a family would set up a rough frame of boughs and cover it with twigs and brush. Scattered marshy places in the basins and valleys grew cattails and bulrushes, called tule. Mats, or fringes, made from their stems were used to cover some houses. Bundles of long, coarse grass were used like shingles on others. Usually the builders dug a pit about two feet deep under the house. This saved wall building and kept drafts off the floor. Storage baskets woven of twigs were set on platforms to keep animals out of the seeds.

* For the winter camp, the Indians of southern California heaped earth over the huts to make them warm. The tribes of northern California could get redwood and split it with wedges of elk or deer antlers. They tied these slabs to frames and built better houses than did tribes to the east and south.

PIZGAH - WACCAMAW

Pizgah Village at Warren Wilson, North Carolina

http://rla.unc.edu/lessons/Lesson/L304/L304.htm

PLANK HOUSE

|

|

PUEBLO

http://www.kstrom.net/isk/maps/houses/pueblo.html

SOUTHWEST DWELLINGS

SERRANO

The native clans who lived in the San Bernardino Mountains and its foothills to the north, south, east, and west were called Serranos by the Spanish. The Serranos also lived along the northern slopes of the San Gabriel range at least as far west as Big Rock Creek. The Spanish term Serrano meant "mountain people." The Serranos called themselves Takhtam or "people.”

Like other native culture groups living in coastal and interior southern California, the Serrano shared cultural traits and a common language, but not a single paramount chief or ruler. The villages and village chiefs who were found among the Serrano, as among other groups, were politically independent, and did not have to answer to a central authority. Village chiefs did participate in alliances and cooperation with other communities, however. Each large winter village and its surrounding territory, ruled by an independent religious and political chief, was occupied by a clan comprised of families related in the male line.

From: http://www.avim.parks.ca.gov/people/ph_serrano.shtml

Crow Teepee

Teepee Gallery

Shows how a teepee is constructed

TIPIS

http://www.kstrom.net/isk/maps/houses/tipi.html

Hidatsa Teepe and Lodge

Housing

drawings

|

|

TEPEE FRAME |

TWO TEPEES |

NEZ PERCE

OTTAWA

The Ottawa tribe lived in a variety of houses. During the winter, the Ottawa tribe used the long house.The long house had a long rectangular shape. The long house was 20 feet wide and 100 feet long. The Ottawa tribe would use the long house because in the winter they would settle in and stay in one place for a while.

During the summer, the Ottawa tribe used the wigwam house. The wigwam house was made circular about 15 feet across. The wigwam house was made of cattail mats and weatherproof birch bark strips.The Ottawa tribe used the wigwam house because in the summer they followed the buffalo so they needed a house they could move very easily.

POMO - TULE HOUSING

The Pomo built houses shaped like an inverted circular or elliptical bowl,

using the

framework willow poles thrust in the ground and transverse oaken hoops. The

thatch consisted of three

layers. Held together by horizontal poles.

|

|

| Modern Construction techniques used |

Modern Chickee |

The chickee was constructed with cypress logs and palm thatch leaves woven together by vines or thin ropes. It had no walls only a thatched roof that covered the area around the upward standing cypress logs submerged shallowly into the earth. After time the Seminoles perfected their housing by adding another level to their chickee making them two stories high with living quarters for those more fortunate.

Shinnecock ( At the Level Land ) Originally a part of the Metoac Indians of Long Island

SHOSHONE ENCAMPMENT

A Shoshone encampment in the Wind River Mountains of Wyoming, photographed by W. H. Jackson, 1870.

(Courtesy Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives [#1668].

TILLAMOOK PLANK HOUSE PLANS

WAGINOGANS

AND OTHER INDIAN HOMES

descriptions - no pix

WAMPANOAG - WEETU

After the frame had been erected, the women covered the roof and sides with six to nine-foot strips of bark from the elm, chestnut, birch or oak, lapping them like great shingles, andsewing them together with a thread from evergreen tree roots. As Gookin noted, instead of bark for roofing, they might fasten mats which were woven from reeds, flags, sedge or, for lack of better material, cornstalks-all neatly sewed together “with needles made from the splinter bones of a crane's legge with thread of their Indian hempe.”

For winter the home needed two thicknesses of mats on both roof and sides, the interior one finely woven, perhaps decorated also. Winslow reported: "The houses were double matted, for as they were matted without, so were they within, with newer & fairer matts.” These rendered the whole dwelling watertight. It was kept clean with a cedar broom.

WATTLE AND DAUB

Prior to the 18th century, most of Georgia was home to Native Americans known

as the Creek Indians.

The name Creek came from the shortening of "Ocheese Creek" Indians - a name

given by the

English to the native people along the Ocheese Creek (or the Ocmulgee

River).

The Creek Indian Lodge in the Children's Garden is an example of a wattle

and daub house. Wattle and daub houses appeared in the Southeastern United

States during the Mississippian period (800-1540 AD). The building, built

by Native Americans from EarthKeepers and Company, consists of a rough timber

frame structure frame structure that uses round posts, often poplar or pine,

(our wattle daub building uses red cedar, locust and pine) between 4 to 8

inches in diameter. The cedar is considered a sacred wood and is used as

a natural insect repellent. The locust has been used on the corner posts

and is very rot resistant. The pine wood used in the rafters is believed

to protect the home from illness.

The Creek Indians built their homes as organic structures to "live in medicine." The posts are held together with a combination of tree bark and cow and elk hide. Hemp roping has been used to tie rafters together on the roof. Thin branches, almost always river cane called wattles are woven in and out of the posts horizontally and close together. A combination of clay and grass is then pressed or "daubed" into the wattle. Our wattle daub house uses cedar shakes as the roofing material. The is a fire pit in the center of the floor and a smoke hole in the roof. The roof is tall so that animal hide, meat and tobacco could be hung. These items were then smoked to preserve their freshness. The paintings on the door represent the tribe and clan of the occupants. Most of the wattle and daub houses were occupied in the winter and an open ramada or porch-like structure was added for sleeping and cooking in the summer. These houses were usually very well built, lasting 30 to 40 years.

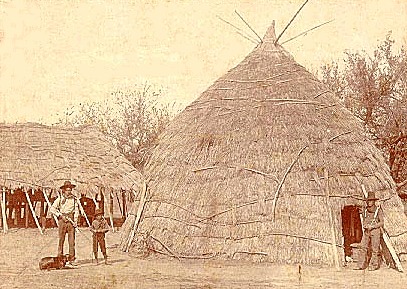

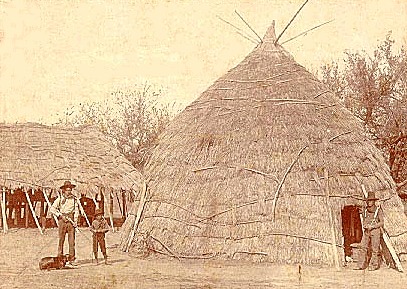

WITCHITA GRASS HUT

They were big, too. Early explorers have described them as being 15 to

30 feet across.

The Caddoan houses were very similar The houses were shaped like giant cones.

Each house had

10 to 12 beds in it. In the center of the roof was a small hole to let out

the smoke

from the fire which was always placed in the middle of the house floor.

There was also a kitchen in these houses. Not like the ones we have today,

of course,

but it was a hollowed out tree trunk that was used to grind corn and prepare

meals.

When the Wichita went on their winter buffalo hunts they lived in

tepees just like other Plains Indians.

ZUNI PUEBLO DWELLINGS

NATIVE AMERICAN ART AND

TECHNOLOGY

NATIVE AMERICAN ATROCITIES

NATIVE AMERICANS - A THOUSAND LIES

DREAMS OF THE GREAT EARTHCHANGES

MAIN INDEX