| 10-12-08 - DREAM I was taking care of a

young blonde infant, whom they called Bomi. His mother was a blonde

with fly-away hair. I found out then, when

his other female relatives came to visit that their name was really Boehme

and they all had the fly-away blonde hair - even through several

generations of women.

Boehme's Heart

Symbol by early 17th-century Christian mystic Jakob

Boehme

including a tetractys of flaming Hebrew letters of the Tetragrammaton

|

Jakob Boehme - (1575-1624), German Lutheran

theosophical author

Boehme, the German mystic, was born in the East German town

of Goerlitz in 1575. He had little in the way of an education

and made his living as a shoemaker; he married and had four

children.

One day in his

master’s shoe shop, a mysterious stranger entered who, while he

seemed to possess but little of this world’s goods, appeared to

be most wise and noble in spiritual attainment. The stranger

asked the price of a pair of shoes, but young Böhme did not dare

to name a figure, for fear that he would displease his master.

The stranger insisted and Böhme finally placed a valuation which

he felt was all that his master possibly could hope to secure

for the shoes. The stranger immediately bought them and

departed. A short distance down the street the mysterious

stranger stopped and cried out in a loud

voice, "Jakob, Jakob, come forth." In amazement and fright,

Boehme ran out of the house. The strange man fixed his eyes upon

the youth—great eyes which sparkled and seemed filled with

divine light. He took the boy’s right hand and addressed him as

follows: "Jakob, thou art little but shall be great, and become

another Man, such a one as at whom the World shall wonder.

Therefore be pious, fear God, and reverence His Word. Read

diligently the Holy Scriptures, wherein you have Comfort and

Instruction. For thou must endure much Misery and Poverty, and

suffer Persecution, but be courageous and persevere, for God

loves, and is gracious to thee." Deeply impressed by the

prediction, Boehme became ever more intense in his search for

truth. At last his labors were rewarded. For seven days he

remained in a mysterious condition during which time the

mysteries of the invisible world were revealed to him. It has

been said of Jakob Boehme that he revealed to all mankind the

deepest secrets of alchemy.

His thought drew on interests including Paracelsus,

the Kabbala, alchemy and the Hermetic tradition. His first

written work, Aurora, went unfinished, but drew to him a small

circle of followers. Like Eckhart and others, Boehme's thought

drew fire from the church authorities, who silenced Boehme for

five years before he continued writing in secrecy. He again

raised the cockles of church authorities, and he was banished

from his home. He died soon thereafter, in 1624, after returning

home from Dresden. His last words spoken, as he was surrounded

by his family, were reported to be, "Now I go hence into

Paradise." His thought has since influenced major figures in

philosophy, especially German Romantics such as Hegel, Baader,

and Schelling. Indirectly, his influence can be traced to the

work of Schopenhauer, Nietzsche, Hartmann, Bergson, and

Heidegger. Paul Tillich and Martin Buber drew heavily from his

work -- as did the psychologist, Carl Jung, who made numerous

references to Boehme in his writings.

|

|

|

Diagram by Boehme, incorporating the Kabbalistic

Tree of Life,

the

traditional Four Elements,

a Christian mandala, and other themes

From an early age he saw visions, and throughout his life he claimed

to be divinely inspired. In his manuscript The Morning Redness Arising,

written in 1612, he recorded his visions and expounded the attributes of

God. The work

was condemned as heretical by local ecclesiastical and civil authorities,

and Boehme was forced to flee to Dresden, Saxony. There he was cleared of

charges of heresy and allowed to return to Görlitz. His best-known

treatises include Of the Three Principles of the Nature of God,

(1619) and The Way to Christ, (1624), The Signature of all

Things, and Mysterium Magnum.

As well as alchemical themes his writings contain

Kabbalistic

concepts. Boehme describes the absolute nature of God as the abyss, the

nothing and the all, the primordial depths from which the creative will

struggles forth to find manifestation and self-consciousness. The Father,

who is groundless Will (c.f. Kabbalah -

Keter the

first principle is identified with Will), issues forth the Son, who is

Love.

Boehme held that everything exists and is intelligible only through

its opposite. Thus, he believed, evil is a necessary element in goodness,

for without evil the will would become inert and progress would be

impossible. Evil is a result of the striving of single elements of Deity

to become the whole; conflict ensues as man and nature strive to achieve

God. God himself, according to Boehme, contains conflicting elements and

antithetical principles within His nature. (c.f.

Sri

Aurobindo - the

Supermind

(Godhead Truth-Consciousness) which contains and reconciles all opposites

within Itself)

Although Boehme's style is very turgid and heavy, his works were

widely read and popular in Germany, the Netherlands, and Great Britain.

His English followers called themselves Behmenists. Many of them later

were absorbed into the Quaker movement. Boehme's writings have influenced

modern

Western thought in both philosophy and theology. He exerted a

profound influence on the philosophies of Baader, Schelling,

Hegel,

and Schopenhauer. His ideas have also had a formative influence on

Theosophy.

Boehme's Leben

Boehme's Mysterium Magnum

Drawing on the left by Jacob

Boehme from his Theosophische Wercke, Amsterdam, 1682.

Note the Phoenix (soul) of

rebirth rising through the Alpha-Omega ‘gap’ in the cycle as

symbolised by the Ouroborus

(serpent-snake) and where it is swallowing its own tail.

|

"Aurora" and writings

Boehme had mystical experiences throughout his youth,

culminating in a

vision in 1600 that he received through observing the

exquisite beauty of a beam of sunlight reflected in a

pewter dish. He believed this vision revealed to him the

spiritual structure of the world, as well as the

relationship between God and man, and good and evil. At

the time he chose not to speak of this experience openly,

preferring instead to continue his work and raise a

family.Jacob Boehme’s persecutions and suffering

began with the publication of his first book, "Aurora," at

the age of thirty-five. then not withstanding five years

of enforced silence, banishment from his home town, and an

ecclesiastical trial for heresy, his "interior wisdom"

began to be recognized by the nobility of Germany; but at

this time, at the age of forty-nine, Boehme died, "happy,"

as he said, "in the midst of the heavenly music of the

paradise of God."

Then after another vision in 1610, he began writing his

first treatise, Aurora, or Die Morgenroete im Aufgang.

Aurora was circulated in manuscript form until a copy fell

into the hands of Gregorius Richter, the chief pastor of Görlitz,

who considered it

heretical and threatened Boehme with exile if he did not stop

writing. After years of silence, Boehme's friends and patrons

persuaded him to start again, and circulated his writings in

handwritten copies. His first printed book, Weg zu Christo

(The

Way to Christ, 1623), caused another scandal; he spent the

last year of his life in exile in

Dresden, returning to Görlitz only to die. In this short

period, Boehme produced an enormous amount of writing, including

his major works De Signatura Rerum and Mysterium Magnum.

He also developed a following throughout Europe, where his

followers were known as

Behmenists.

The son of Boehme's chief antagonist, the pastor primarius of

Görlitz

Gregorius Richter, edited a collection of extracts from his

writings, which were afterwards published complete at

Amsterdam with the help of

Coenraad van Beuningen in the year 1682. Boehme's full works

were first printed in 1730.

Theology

The chief concern of Boehme's writing was the nature of

sin,

evil,

and

redemption. Consistent with

Lutheran theology, Boehme preached that humanity had fallen

from a state of

divine grace to a state of sin and suffering, that the forces

of evil included fallen

angels

who had rebelled against

God,

and that God's goal was to restore the world to a state of grace.

Where Boehme appeared to depart from accepted

theology (though this was open to question due to his somewhat

obscure, oracular style) was in his description of

the Fall as a necessary stage in the evolution of the

Universe.[2]

A difficulty with his theology is the fact that he had a

mystical vision, which he reinterpreted and reformulated.[3]

To Boehme, in order to reach

God,

man has to go through

hell

first. God exists without

time

or

space, he regenerates himself through

eternity, so Boehme, who restates the

trinity as truly existing but with a novel interpretation.

God, the Father is fire, who gives birth to his son, whom Boehme

calls light. The

Holy Spirit is the living principle, or the divine life.[4]

Cosmology

In Boehme's

cosmology, it was necessary for humanity to depart from God,

and for all original unities to undergo differentiation, desire,

and conflict -- as in the rebellion of

Satan,

the separation of

Eve from

Adam, and their acquisition of the knowledge of good and evil

-- in order for creation to evolve to a new state of redeemed

harmony that would be more perfect than the original state of

innocence, allowing God to achieve a new self-awareness by

interacting with a creation that was both part of, and distinct

from, Himself.

Free will becomes the most important gift God gives to

humanity, allowing us to seek divine grace as a deliberate choice

while still allowing us to remain individuals.

Boehme saw the incarnation of

Christ not as a sacrificial offering to cancel out human sins,

but as an offering of love for humanity, showing God's willingness

to bear the suffering that had been a necessary aspect of

creation. He also believed the incarnation of Christ conveyed the

message that a new state of harmony is possible. This was somewhat

at odds with Lutheran

dogma,

and his suggestion that God would have been somehow incomplete

without the Creation was even more controversial, as was his

emphasis on faith and self-awareness rather than strict adherence

to dogma or

scripture.

Marian views

Boehme believed that the

Son of God became human through the

Virgin Mary. Before the birth of Christ, God recognized

himself as a

virgin. This virgin is therefore a mirror of God's

wisdom and

knowledge.[5]

Boehme follows Luther, in that he views Mary within the context of

Christ. Unlike Luther, he does not address himself to dogmatic

issues very much, but to the human side of Mary. Like all other

women, she was human and therefore subject to sin. Only after God

elected her with his grace to become the mother of his son, did

she inherit the status of sinlessness.[6]

Mary did not move the Word, the Word moved Mary, so Boehme,

explaining that all her grace came from Christ. Mary is "blessed

among women" but not because of her qualifications, but because of

her

humility. Mary is an instrument of God, an example, what God

can do: It shall not be forgotten in all eternity, that God became

human in her.[7]

Boehme, unlike Luther does not believe that Mary was the

Ever Virgin. Her virginity after the birth of Jesus is

unrealistic to Boehme. The true salvation is Christ not Mary. The

importance of Mary, a human like every one of us, is that she gave

birth to Jesus Christ as a human being. If Mary would not have

been human, to Boehme, Christ would be a stranger and not our

brother. Christ must grow in us as he did in Mary. She became

blessed by accepting Christ. In a reborn Christian, like in Mary,

all that is temporal disappears and only the heavenly part remains

for all eternity. Boehme's peculiar theological language, involving

fire,

light

and

spirit, which permeates his theology and Marian views, does

not distract much from the fact that his basic positions are

Lutheran, with the one exception of the virginity of Mary, where

he holds a more temporal view.[8]

Influences

Boehme's writing shows the influence of

Neoplatonist and

alchemical writers such as

Paracelsus, while remaining firmly within a Christian

tradition. He has in turn greatly influenced many

anti-authoritarian and mystical movements, such as the

Religious Society of Friends, the

Philadelphians, the

Gichtelians, the

Society of the Woman in the Wilderness, the

Ephrata Cloister, the

Harmony Society, the

Zoarite Separatists,

Martinism, and

Christian

theosophy. Boehme was also an important source of German

Romantic philosophy, influencing

Schelling in particular.

[9] In

Richard Bucke's 1901 treatise Cosmic Consciousness,

special attention was given to the profundity of Böhme's spiritual

enlightenment, which seemed to reveal to Boehme an ultimate

nondifference, or

nonduality, between human beings and God. Boehme is also an

important influence on the ideas of the English Romantic poet,

artist and mystic

William Blake.

In later works—The Way to Christ (1622),

The Mysterium Magnum (1623), and De

Signatura Rerum (1623)—he praised the spiritual life,

criticized the growing formalism of the Lutheran church, expressed

traditional German mystic teachings, discussed Paracelsan

speculative alchemy, and considered questions of freedom, good,

and evil. Alcott, who purchased the English translation (by John

Sparrow and John Elliston) in William Law’s four-volume edition in

1842, extolled Boehme as “the master mind of these last

centuries.”

Quote

"When thou art gone forth wholly from the creature [human],

and art become nothing to all that is nature and creature, then

thou art in that eternal one, which is God himself, and then thou

shalt perceive and feel the highest virtue of love. Also, that I

said whosoever findeth it findeth nothing and all things; that is

also true, for he findeth a supernatural, supersensual Abyss,

having no ground, where there is no place to dwell in; and he

findeth also nothing that is like it, and therefore it may be

compared to nothing, for it is deeper than anything, and is as

nothing to all things, for it is not comprehensible; and because

it is nothing, it is free from all things, and it is that only

Good, which a man cannot express or utter what it is. But that I

lastly said, he that findeth it, findeth all things, is also true;

it hath been the beginning of all things, and it ruleth all

things. If thou findest it, thou comest into that ground from

whence all things proceed, and wherein they subsist, and thou art

in it a king over all the works of God." [The Way to Christ,

1623]

Jacob Boehme was concerned about "the salvation of his

soul." Although daily occupied, first as a shepherd, and

afterward as a shoemaker, he was always an earnest student of

the Holy Scriptures; but he could not understand "the ways of

God," and he became "perplexed, even to melancholy, — pressed

out of measure." He said: "I knew the Bible from beginning to

end, but could find no consolation in Holy Writ; and my spirit,

as if moving in a great storm, arose in God, carrying with it my

whole heart, mind and will and wrestled with the love and mercy

of God, that his blessing might descend upon me, that my mind

might be illumined with his Holy Spirit, that I might understand

his will and get rid of my sorrow . . .

"I had always thought much of how I might inherit

the kingdom of heaven; but finding in myself a powerful

opposition, in the desires that belong to the flesh and

blood, I began a battle against my corrupted nature; and with

the aid of God, I made up my mind to overcome the inherited evil

will, . . . break it, and enter wholly into the love of God in

Christ Jesus . . . I sought the heart of Jesus Christ, the

center of all truth; and I resolved to regard myself as dead in

my inherited form, until the Spirit of God would take form in

me, so that in and through him, I might conduct my life.

"I stood in this resolution, fighting a battle with

myself, until the light of the Spirit, a light entirely foreign

to my unruly nature, began to break through the clouds. Then,

after some farther hard fights with the powers of darkness, my

spirit broke through the doors of hell, and penetrated even unto

the innermost essence of its newly born divinity where it was

received with great love, as a bridegroom welcomes his beloved

bride.

"No word can express the great joy and triumph I

experienced, as of a life out of death, as of a resurrection

from the dead! . . . While in this state, as I was walking

through a field of flowers, in fifteen minutes, I saw through

the mystery of creation, the original of this world and of all

creatures. . . . Then for seven days I was in a continual state

of ecstasy, surrounded by the light of the Spirit, which

immersed me in contemplation and happiness. I learned what God

is, and what is his will. . . . I knew not how this happened to

me, but my heart admired and praised the Lord for it!"

MUSIC VIDEOS

VICTORIA - O MAGNUM MYSTERIUM

MORTIN LAURIDSON - O MAGNUM MYSTERIUM

O

MAGNUM MYSTERIUM - MORTIN LAURIDSON LISTENING ON STAGE

JAKOB

BOEHME - MYSTERIUM

-

John Wesley, in his day, required all of his

preachers to study the writings of Jacob Boehme; and the

learned theologian, Willam Law, said of him: "Jacob

Boehme was not a messenger of anything new in religion,

but the mystery of all that was old and true in religion

and nature, was opened up to him," — "the depth of the

riches, both of the wisdom and knowledge of God."

See also

Works

- Aurora: Die Morgenröte im Aufgang (unfinished)

(1612)

- The Three Principles of the Divine Essence (1612)

- The Threefold Life of Man (1620)

- Answers to Forty Questions Concerning the Soul

(1620)

- The Treatise of the Incarnations: (1620)

- I. Of the Incarnation of Jesus Christ

- II. Of the Suffering, Dying, Death and Resurrection

of Christ

- III. Of the Tree of Faith

- The Great Six Points (1620)

- Of the Earthly and of the Heavenly Mystery (1620)

- Of the Last Times (1620)

- De Signatura Rerum (1621)

- The Four Complexions (1621)

- Of True Repentance (1622)

- Of True Resignation (1622)

- Of Regeneration (1622)

- Of Predestination (1623)

- A Short Compendium of Repentance (1623)

- The Mysterium Magnum (1623)

- A Table of the Divine Manifestation, or an Exposition

of the Threefold World (1623)

- The Supersensual Life (1624)

- Of Divine Contemplation or Vision (unfinished)

(1624)

- Of Christ's Testaments (1624)

- I. Baptism

- II. The Supper

- Of Illumination (1624)

- 177 Theosophic Questions, with Answers to Thirteen of

Them (unfinished) (1624)

- An Epitome of the Mysterium Magnum (1624)

- The Holy Week or a Prayer Book (unfinished) (1624)

- A Table of the Three Principles (1624)

- Of the Last Judgement (lost) (1624)

- The Clavis (1624)

-

Sixty-two Theosophic Epistles (1618-1624)

Books in Print

- The Way to Christ (inc. True Repentance, True

Resignation, Regeneration or the New Birth, The Supersensual

Life, Of Heaven & Hell, The Way from Darkness to True

Illumination) edited by

William Law, Diggory Press

ISBN 978-1846857911

References

- ^

[1]. Some sources

e.g. this one say he was born "on or soon before" 24 April

1575.

- ^ F.von

Ingen, Jacob Böhme in Marienlexikon, Eos, St.Ottilien 1988, 517

- ^ See

Schopenhauer's

On the Fourfold Root of the Principle of Sufficient Reason,

Ch II, 8

External links

Wikisource has original works written by or about:

The Saints are listed in

Liber XV, also known as the Gnostic Mass, which is the

central rite of

Ordo Templi Orientis and its ecclesiastical arm,

Ecclesia Gnostica Catholica. They are found in the

fifth

Collect of Liber XV, titled "The Saints."

In the

Catholic and Orthodox churches, a saint is a person

who has been canonised (officially recognized) after their

death. However, in the EGC, death is not necessarily a

prerequisite for sainthood, since

Aleister Crowley was certainly alive when he wrote

Liber XV (he included himself twice, in fact). The Gnostic

Saints are generally considered to those who have embodied

the essential principles of Thelema and formed a line of

adepts through the ages.

The only Gnostic Saint to have been officially added

to the original list is

William Blake, based on a discovered writing by

Aleister Crowley who described him as such. It is also

considered approprate to include the name of deceased

Grand Masters of O.T.O., such as

Hymenaeus Alpha.

From Liber XV, the entire Collect is written below.

Those names in italics are commemorated in ordinary

masses, whereas the entire list is entoned for a

"celebratory mass," such as when it is performed in

conjunction with a

Wedding.

Collect V: The Saints

"LORD of Life and Joy, that art the might of man, that art

the essence of every true god that is upon the surface of the

Earth, continuing knowledge from generation unto generation, thou

adored of us upon heaths and in woods, on mountains and in caves,

openly in the marketplaces and secretly in the chambers of our

houses, in temples of gold and ivory and marble as in these other

temples of our bodies, we worthily commemorate them worthy that

did of old adore thee and manifest they glory unto men,

Lao-tzu,

Siddhartha,

Krishna,

Tahuti,

Mosheh,

Dionysus,

Mohammed,

To Mega Therion,

Hermes,

Pan,

Priapus,

Osiris,

Melchizedek,

Khem,

Amoun,

Mentu,

Heracles,

Orpheus,

Odysseus,

Vergilius,

Catullus,

Martialis,

Rabelais,

Swinburne,

Apollonius Tyanæus,

Simon Magus,

Manes,

Pythagoras,

Basilides,

Valentinus,

Bardesanes,

Hippolytus,

Merlin,

Arthur,

Kamuret,

Parzival,

Carolus Magnus,

William of Schyren,

Frederick of Hohenstaufen,

Roger Bacon,

Jacobus Burgundus Molensis the Martyr,

Christian Rosencreutz,

Ulrich von Hutten,

Paracelsus,

Michael Maier,

Roderic Borgia Pope Alexander the Sixth,

Jacob Boehme,

Francis Bacon Lord Verulam,

Andrea,

Robertus de Fluctibus,

Johannes Dee,

Sir Edward Kelly,

Thomas Vaughan,

Elias Ashmole,

Molinos,

Adam Weishaupt,

Wolfgang von Goethe,

William Blake,

Ludovicus Rex Bavariae,

Richard Wagner,

Alphonse Louis Constant,

Friedrich Nietzsche,

Hargrave Jennings,

Carl Kellner,

Forlong dux,

Sir Richard Payne Knight,

Paul Gaugin,

Sir Richard Francis Burton,

Doctor Gerard Encausse,

Doctor Theodor Reuss,

Sir Aleister Crowley

—Oh Sons of the Lion and the Snake! With all thy saints we

worthily commemorate them worthy that were and are and are to

come.

|

Christianity as a mystery religion

The word used by

Early Christians to indicate the

Christian Mystery is μυστήριον (mysterion). The

Old Testament versions use the word mysterion as an equivalent

for the

Hebrew sôd, "secret" (Proverbs

20:19;

Judith 2:2;

Sirach 22:27;

2 Maccabees 13:21). In the

New Testament the word mystery is applied ordinarily to the

sublime revelation of the

Gospel (Matthew

13:11;

Colossians 2:2;

1 Timothy 3:9;

1 Corinthians 15:51), and to the

Incarnation and life of the

Saviour and His manifestation by the preaching of the

Apostles (Romans

16:25;

Ephesians 3:4; 6:19;

Colossians 1:26; 4:3). Theologians give the name mystery

to revealed truths that surpass the powers of natural

reason,[8]

so, in a narrow sense, the Mystery is a truth that transcends the

created intellect. The impossibility of obtaining a rational

comprehension of the Mystery leads to an inner or hidden

way of comprehension of the Christian Mystery which is

indicated by the term esoteric in Esoteric Christianity.

[9]

Even though revealed and believed, the Mystery remains

nevertheless obscure and veiled during the mortal life, if the

deciphering of the mysteries, made possible by esotericism, does

not intervene.[10]

This

esoteric knowledge would allow a deep comprehension of the

Christian mysteries which otherwise would remain obscure.

Ancient roots

Some modern scholars believe that in the early stages of

Christianity a nucleus of oral teachings were inherited from

Palestinian and

Hellenistic

Judaism which formed the basis of a secret oral tradition,

which in the

4th century came to be called the

disciplina arcani.[11][7][12]

Important influences on Esoteric Christianity are the Christian

theologians

Clement of Alexandria and

Origen, the main figures of the

Catechetical School of Alexandria.[13]

Origen was a most prolific writer - according to

Epiphanius, he wrote about 6,000 books[14]

- making it a difficult task to define the central core of his

teachings. The original

Greek text of his main theological work De Principiis

only survives in fragments, while a

5th century

Latin

translation was cleared of controversial teachings by the

translator

Rufinus, making it hard for modern scholars to rebuild

Origen's original thoughts. Thus, it is unclear whether

reincarnation and the

pre-existence of

souls

formed part of Origen's beliefs.

While hypothetically considering a complex multiple-world

transmigration scheme in De Principiis, Origen denies

reincarnation in unmistakable terms in his work,

Against Celsus and elsewhere.[15][16]

Despite this apparent contradiction, most modern Esoteric

Christian movements refer to Origen's writings (along, with other

Church Fathers and

biblical passages[17])

to validate these ideas as part of the Esoteric Christian

tradition.[18]

Early modern esotericism

In the later

Middle Ages forms of

Western esotericism, for example

alchemy and

astrology, were constructed on Christian foundations,

combining Christian theology and doctrines with esoteric concepts.[19]

Giovanni Pico della Mirandola's Apologia ("Apologia J.

Pici Mirandolani, Concordiae comitis" published in 1489) states

that there are two types of "magic",

which are

theurgy (divine magic), and

goetia (demonic magic). These disciplines were explained as

the "Operation of the Stars", just as

alchemy was the "Operation of the Sun", and

astrology the "Operation of the Moon."

Kabbalah was also an active discipline. Esoteric Christian

practitioners might practice these forms or traditions, which made

them

adepts, alchemists, astrologists, and

Hermetic Qabalists, while still being Esoteric Christian

practitioners of a passive discipline which helped them better use

the "mystery knowledge" they gained from the elite, or Higher

Beings.

In the

17th century this was followed up by the development of

Theosophy and

Rosicrucianism.[20]

The

Behmenist movements also developed around this time. In the

18th century,

Freemasonry came about.

Modern forms of Esoteric

Christianity

Many modern Esoteric Christian movements admit

reincarnation among their beliefs, as well as a complex

energetic structure for the human being (such as

etheric body,

astral body,

mental body and

causal body). These movements point out the need of an inner

spiritual work which will lead to the renewal of the human person

according to the

Pauline sense.

Max Heindel and

Rudolf Steiner gave several spiritual exercises in their

writings to help the evolution of the follower. In the same

direction are

Tommaso Palamidessi's writings, which aim at developing

ascetic techniques and

meditations. According to all of these esoteric scholars, the

ensemble of these techniques (often related with Eastern

meditation practices such as

chakra meditation or

visualization) will lead to

salvation and to the total renewal of the human being. This

process usually implies the constitution of a spiritual body apt

to the experience of

resurrection (and therefore called, in Christian terms,

resurrection body).[21][22][23]

See also

Schools

Traditions

Disciplines

Lineage

Central concepts

External links

Notes

- ^

Western Esotericism and the Science of Religion: Selected

Papers Presented at the 17th Congress

- ^

Besant, Annie (2001). Esoteric Christianity or the Lesser

Mysteries. City: Adamant Media Corporation.

ISBN 9781402100291.

- ^ From

the Greek ἐσωτερικός (esôterikos, "inner"). The term

esotericism itself was coined in the 17th century. (Oxford

English Dictionary Compact Edition, Volume 1,Oxford University

Press, 1971, p. 894.)

- ^

Wouter J. Hanegraaff, Antoine Faivre, Roelof van den Broek,

Jean-Pierre Brach, Dictionary of Gnosis & Western Esotericism,

Brill 2005.

- ^

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary: esotericism

- ^

Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary: esoteric

- ^

a

b

G.G. Stroumsa, Hidden Wisdom: Esoteric Traditions and the

Roots of Christian Mysticism, 2005.

- ^ The

Catholic Encyclopedia, Volume X. Published 1911

- ^

Besant, Annie (2001). Esoteric Christianity or the Lesser

Mysteries. City: Adamant Media Corporation.

ISBN 9781402100291.

- ^

Tommaso Palamidessi, Introduction to Major and Minor

Mysteries, ed. Archeosofica, 1971

- ^

Frommann, De Disciplina Arcani in vetere Ecclesia

christiana obticuisse fertur, Jena 1833.

- ^ E.

Hatch, The Influence of Greek Ideas and Usages upon the

Christian Church, London, 1890, Chapter 10.

- ^

Jean Danielou, Origen, translated by Walter Mitchell,

1955.

- ^

Haer., lxiv.63

- ^

Catholic Answers,

Quotes by Church Fathers Against Reincarnation, 2004.

- ^

John S. Uebersax,

Early Christianity and Reincarnation: Modern Misrepresentation

of Quotes by Origen, 2006.

- ^

See

Reincarnation and Christianity

- ^

Archeosofica,

Articles on Esoteric Christianity (classical authors)

- ^

Antoine Faivre, L'ésotérisme, Paris, PUF (« Que

sais-je?»), 1992.

- ^

Weber, Charles,

Rosicrucianism and Christianity in

Rays from the Rose Cross, 1995

- ^

Rudolf Steiner, Christianity As Mystical Fact,

Steinerbooks.

- ^

Tommaso Palamidessi,

The Guardians of the Thresholds and the Evolutionary Way,

Archeosofica, 1978.

- ^

Max Heindel, The Mystical Interpretation of Easter,

Rosicrucian Fellowship.

- ^

Heindel, Max,

Freemasonry and Catholicism,

ISBN 0-911274-04-9

|

Christian mysticism

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopediaChristian

mysticism is traditionally practised through the

disciplines of:

In the tradition of

Mystical Theology,

Biblical texts are typically interpreted

metaphorically, for example in

Jesus'

"Sermon

on the Mount" (Matthew

5–7) the text, in its totality, is held to contain the way for

direct union with

God.

Also, in the

contemplative and

eremitic tradition of the

Carmelite "Book

of the First Monks",

1

Kgs. 17:3-4 is the central Biblical text around which the work

is written.

Whereas Christian doctrine generally maintains that God

dwells in all Christians and that they can experience God directly

through belief in Jesus, Christian mysticism aspires to apprehend

spiritual truths inaccessible through intellectual means,

typically by learning how to think like Christ.

William Inge divides this scala perfectionis into three

stages: the "purgative" or

ascetic stage, the "illuminative" or contemplative stage, and

the "unitive" stage, in which God may be beheld "face to face."

Biblical foundations

The tradition of Christian Mysticism is as old as

Christianity itself. At least three texts from the

New Testament set up themes that recur throughout the recorded

thought of the Christian mystics. The first,

Galatians 2:20, says that:

I am

crucified with Christ: nevertheless I live; yet not I, but

Christ liveth in me, and the life which I now live in the flesh

I live by the faith of the Son of God, who loved me, and gave

himself for me. (KJV)

The second important scriptural text for Christian mysticism

is

1 John 3:2:

Beloved, now we are the sons of God, and it doth not yet

appear what we shall be: but we know that, when he shall appear,

we shall be like him; for we shall see him as he is.

The third such text, especially important for

Eastern Christian mysticism, is found in

II Peter 1:4:

...[E]xceedingly great and precious promises [are given

unto us]; that by these ye might be partakers of the divine

nature, having escaped the corruption that is in the world

through lust. (emphasis added)

Two major themes of Christian mysticism are (1) a complete

identification with, or

imitation of Christ, to achieve a unity of the human

spirit with the spirit of God; and (2) the perfect vision of God,

in which the mystic seeks to experience God "as he is," and no

more "through a glass, darkly." (1

Corinthians 13:12)

Other mystical experiences are described in other passages.

In

2 Corinthians 12:2–4, Paul sets forth an example of a possible

out-of-body experience by someone who was taken up to the

"third

heaven", and taught unutterable mysteries:

I knew a man in Christ above fourteen years ago, (whether

in the body, I cannot tell; or whether out of the body, I cannot

tell: God knoweth;) such an one caught up to the third heaven.

And I knew such a man, (whether in the body, or out of the body,

I cannot tell: God knoweth;) how that he was caught up into

paradise, and heard unspeakable words, which it is not lawful

for a man to utter.

Perhaps a similar experience occurred at the

Transfiguration of Jesus, an incident confirmed in each of the

Synoptic Gospels. Here Jesus led three of his apostles,

Peter,

John, and

James, to pray at the top of a mountain, where he became

transfigured. Jesus's face shone like the sun, and he was clad in

brilliant white clothes.

Elijah and

Moses

appeared with Jesus, and talked with him, and then a bright cloud

appeared overhead, and a voice from the cloud proclaimed, "This is

my beloved Son: hear him."

Practice

While such phenomena are associated with mysticism in

general, including the Christian variety, for Christians the major

emphasis concerns a spiritual transformation of the

egoic self, the following of a path designed to produce more

fully realized human persons, "created in the Image and Likeness

of God" and as such, living in harmonious communion with God, the

Church, the rest of

humanity, and all creation, including oneself. For Christians,

this human potential is realized most perfectly in Jesus and is

manifested in others through their association with Him, whether

conscious, as in the case of Christian mystics, or unconscious,

with regard to persons who follow other traditions, such as

Gandhi. The

Eastern Christian tradition speaks of this transformation in

terms of

theosis or divinization, perhaps best summed up by an ancient

aphorism usually attributed to

Athanasius of Alexandria: "God became human so that man might

become God."

Going back at least to

Evagrius Ponticus and

Pseudo-Dionysius, Christian mystics have pursued a threefold

path in their pursuit of holiness. While the three aspects have

different names in the different Christian traditions, they can be

characterized as purgative, illuminative, and unitive,

corresponding to body, soul (or mind), and spirit. The first, the

way of purification, is where aspiring Christian mystics start.

This aspect focuses on discipline, particularly in terms of the

human body; thus, it emphasizes prayer at certain times, either

alone or with others, and in certain postures, often standing or

kneeling. It also emphasizes the other disciplines of fasting and

alms-giving, the latter including those activities called "the

works of mercy," both spiritual and corporal, such as feeding the

hungry and sheltering the homeless.

Purification, which grounds Christian spirituality in

general, is primarily focused on efforts to, in the words of

St. Paul, "put to death the deeds of the flesh by the Holy

Spirit" (Romans

8:13). The "deeds of the flesh" here include not only external

behavior, but also those habits, attitudes, compulsions,

addictions, etc. (sometimes called

egoic passions) which oppose themselves to true being and

living as a Christian not only exteriorly, but interiorly as well.

Evelyn Underhill describes purification as an awareness of

one's own imperfections and finiteness, followed by

self-discipline and mortification. Because of its physical,

disciplinary aspect, this phase, as well as the entire Christian

spiritual path, is often referred to as "ascetic,"

a term which is derived from a Greek word which connotes athletic

training. Because of this, in ancient Christian literature,

prominent mystics are often called "spiritual athletes," an image

which is also used several times in the New Testament to describe

the Christian life. What is sought here is salvation in the

original sense of the word, referring not only to one's eternal

fate, but also to healing in all areas of life, including the

restoration of spiritual, psychological, and physical health.

It remains a paradox of the mystics that the passivity at

which they appear to aim is really a state of the most intense

activity: more, that where it is wholly absent no great creative

action can take place. In it, the superficial self compels

itself to be still, in order that it may liberate another more

deep-seated power which is, in the ecstasy of the contemplative

genius, raised to the highest pitch of efficiency. Mysticism:

A Study in Nature and Development of Spiritual Consciousness

by Evelyn Underhill (Public Domain)

The second phase, the path of illumination, has to do with

the activity of the Holy Spirit enlightening the mind, giving

insights into truths not only explicit in scripture and the rest

of the Christian tradition, but also those implicit in nature, not

in the scientific sense, but rather in terms of an illumination of

the "depth" aspects of reality and natural happenings, such that

the working of God is perceived in all that one experiences.

Underhill describes it as marked by a consciousness of a

transcendent order and a vision of a new heaven and a new earth.

The third phase, usually called contemplation in the Western

tradition, refers to the experience of oneself as in some way

united with God. The experience of union varies, but it is first

and foremost always associated with a reuniting with Divine

love, the underlying theme being that God, the perfect

goodness,[3]

is known or experienced at least as much by the heart as by the

intellect since, in the words

1 John 4:16: "God is love, and he who abides in love abides in

God and God in him." Some approaches to classical mysticism would

consider the first two phases as preparatory to the third,

explicitly mystical experience, but others state that these three

phases overlap and intertwine.

Author and mystic

Evelyn Underhill recognizes two additional phases to the

mystical path. First comes the awakening, the stage in which one

begins to have some consciousness of absolute or divine reality.

Purgation and illumination are followed by a fourth stage which

Underhill, borrowing the language of

St. John of the Cross, calls the

dark night of the soul. This stage, experienced by the few, is

one of final and complete purification and is marked by confusion,

helplessness, stagnation of the

will, and a sense of the withdrawal of God's presence. It is

the period of final "unselfing" and the surrender to the hidden

purposes of the divine will. Her fifth and final stage is union

with the object of love, the one Reality, God. Here the self has

been permanently established on a transcendental level and

liberated for a new purpose.[4]

Another aspect of traditional Christian spirituality, or

mysticism, has to do with its communal basis. Even for hermits,

the Christian life is always lived in communion with the

Church, the community of believers. Thus, participation in

corporate worship, especially the

Eucharist, is an essential part of Christian mysticism.

Connected with this is the practice of having a

spiritual director,

confessor, or "soul

friend" with which to discuss one's spiritual progress. This

person, who may be

clerical or

lay,

acts as a spiritual mentor.

Christian mystics

-

Some examples of

Christian mystics:

Notes and references

See also

Bibliography

- Anderson, Robert A. : Church of God? or the Temples of

Satan (A Reference Book of Mysticism & Gnosis), TGS

Publishers, 2006,

ISBN 0-9786249-6-3

- Bernard McGinn: The Foundations of Mysticism: Origins

to the Fifth Century, 1991, reprint 1994,

ISBN 0-8245-1404-1

- Bernard McGinn: The Growth of Mysticism: Gregory the

Great through the 12th Century, 1994, paperback ed. 1996,

ISBN 0-8245-1628-1

-

Evelyn Underhill: Mysticism: A Study in Nature and

Development of Spiritual Consciousness, 1911, reprint 1999,

ISBN 1-85168-196-5

online edition

- Tito Colliander: Way of the Ascetics, 1981,

ISBN 0-06-061526-5

- Thomas E. Powers: Invitation to a Great Experiment:

Exploring the Possibility that God can be Known, 1979,

ISBN 0-385-14187-4

- Richard Foster: Celebration of Discipline: The Path to

Spiritual Growth, 1978,

ISBN 0-06-062831-6

Classics

External links

|

Hallucinations (VISIONS) in the sane

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

A

hallucination (vision) may occur in a person in a state of good mental

and physical health, even in the apparent absence of a transient

trigger factor such as fatigue, intoxication, or

sensory deprivation.

It is not yet widely recognised that hallucinatory

(visionary) experiences are not merely the prerogative of the insane, or

normal people in abnormal states, but that they occur

spontaneously in a significant proportion of the normal

population, when in good health and not undergoing particular

stress or other abnormal circumstance.

The evidence for this statement has been accumulating for

more than a century. Studies of hallucinatory (visionary) experience in the

sane go back to 1886 and the early work of the

Society for Psychical Research,[1][2]

which suggested approximately 10% of the population had

experienced at least one hallucinatory (visionary) episode in the course of

their life. More recent studies have validated these findings; the

precise incidence found varies with the nature of the episode and

the criteria of ‘hallucination’ adopted, but the basic finding is

now well-supported.[3]

Editors note: It has been well

studied in recent years that people can be trained to have

visionary experiences, as well as channel spirits for their wisdom

information.

|

Types

Of particular interest, for reasons to be discussed below,

are those hallucinatory (visionary) experiences of the sane which are characterised by extreme perceptual realism, sometimes to the

extent that the subject does not at first achieve insight, indeed

may only achieve insight after the experience has ended.

Apparitional experiences (ghosts)

An

apparitional experience may be defined as one in which a

subject seems to perceive some person or thing that is not really

there. Self-selected samples tend to report a predominance of

human figures, but apparitions of animals,[4]

and even objects[5]

are also reported. It is interesting to note that the majority of

the human figures reported in such samples are not recognised by

the subject, and of those who are, not all are of deceased

persons, apparitions of living persons also being reported.[6]

Out-of-body experiences

Out-of-body experiences (OBEs) have become to some extent

conflated in the public mind with the concept of the

near-death experience. However, the evidence suggests that the

majority of out-of-body experiences do not occur near death, but

in conditions of either very high or very low arousal.[7]McCreery

[8]has suggested that this

latter paradox may be explained by reference to the fact that

sleep may be approached, not only by the conventional route of low

arousal and deafferentation, but also by the less familiar route

of extreme stress and hyper-arousal.[9]

On this model OBEs represent the intrusion of Stage 1 sleep

processes into waking consciousness.

OBEs are to be regarded as hallucinatory on the grounds that

they are perceptual or quasi-perceptual experiences in which by

definition the ostensible viewpoint is not coincident with the

physical body of the subject. Therefore the normal sensory input,

if any, that the subject is receiving during the experience cannot

correspond exactly to the perceptual representation of the world

in the subject’s consciousness.

As with hallucinatory experiences in general, attempts to

survey samples of the general population have suggested that such

experiences are relatively common, incidence figures of between 15

and 25 percent being commonly reported.[10]

The variation is presumably to be accounted for by the different

types of populations sampled and the different criteria of

‘out-of-body experience’ used.

Dreams and lucid dreams

-

Main articles:

Dream and

Lucid dream

A dream has been defined by some (e.g. Encyclopaedia

Britannica) as a hallucinatory experience during sleep.

A lucid dream may be defined as one in which the dreamer is

aware that he or she is asleep and dreaming. The term ‘lucid

dream’ was first used by the Dutch physician Frederik van Eeden,[11]

who studied his own dreams of this type. The word ‘lucid’ refers

to the fact that the subject has achieved insight into his or her

condition, rather than the perceptual quality of the experience.

Nevertheless, it is one of the features of lucid dreams that they

can have an extremely high quality of perceptual realism, to the

extent that the dreamer may spend time examining and admiring the

perceptual environment and the way it appears to imitate that of

waking life.[12]

Lucid dreams by definition occur during sleep, but they may

be regarded as hallucinatory experiences in the same way as

non-lucid dreams of a vivid perceptual nature may be regarded as

hallucinatory, that is they are examples of 'an experience having

the character of sense perception, but without relevant or

adequate sensory stimulation […]'

[13]

False awakenings in dreams

A

false awakening is one in which the subject seems to wake up,

whether from a lucid or a non-lucid dream, but is in fact still

asleep.[14]

Sometimes the experience is so realistic perceptually (the sleeper

seeming to wake in his or her own bedroom, for example) that

insight is not achieved at once, or even until the dreamer really

wakes up and realises that what has occurred was hallucinatory.

Such experiences seem particularly liable to occur to those who

deliberately cultivate lucid dreams. However, they may also occur

spontaneously and be associated with the experience of

sleep paralysis.

Subtypes

Auditory hallucinations (CLAIRAUDIENCE)

Auditory hallucinations, (clairaudience) and in particular the hearing of a

voice, are thought of as particularly characteristic of people

suffering from

schizophrenia. However, normal subjects also report auditory

hallucinations (clairaudience) to a surprising extent. For example, Bentall and

Slade[15]

found that as many as 15.4% of a population of 150 male students

were prepared to endorse the statement ‘In the past I have had the

experience of hearing a person’s voice and then found that no one

was there’. They add: ‘[…]no less that 17.5% of the [subjects]

were prepared to score the item “I often hear a voice speaking my

thoughts aloud” as “Certainly Applies”. This latter item is

usually regarded as a first-rank symptom of schizophrenia[…]’

Editors note: That is the basic

problem with psychiatrists - they have no or little spiritual

training and don't understand that its normal for people to be

able to speak with spirits and deceased loved ones with a little

effort - and often when they are thinking of a particular spirit

being, particularly during meditation..

Green and McCreery[16]

found that 14% of their 1800 self-selected subjects reported a

purely auditory hallucination, (clairaudience) and of these nearly half involved

the hearing of articulate or inarticulate human speech sounds. An

example of the former would be the case of an engineer facing a

difficult professional decision, who, while sitting in a cinema,

heard a voice saying, ‘loudly and distinctly’: ‘You can’t do it

you know’. He adds: 'It was so clear and resonant that I turned

and looked at my companion who was gazing placidly at the

screen[…] I was amazed and somewhat relieved when it became

apparent that I was the only person who had heard anything.'[17]

This case would be an example of what Posey and Losch[18]

call ‘hearing a comforting or advising voice that is not perceived

as being one’s own thoughts’. They estimated that approximately

10% of their population of 375 American college students had had

this type of experience.

The ‘Sense of Presence’

This is a paradoxical experience in which the person has a

strong feeling of the presence of another person, sometimes

recognised, sometimes unrecognised, but without any apparently

justifying sensory stimulus.

The nineteenth-century American psychologist and philosopher

William James described the experience thus: 'From the way in

which this experience is spoken of by those who have had it, it

would appear to be an extremely definite and positive state of

mind, coupled with a belief in the reality of its object quite as

strong as any direct sensation ever gives. And yet no sensation

seems to be connected with it at all... The phenomenon would seem

to be due to a pure conception becoming saturated with the sort of

stinging urgency which ordinarily only sensations bring.'[19]

The following is an example of this type of experience: 'My

husband died in June 1945, and 26 years afterwards when I was at

Church, I felt him standing beside me during the singing of a

hymn. I felt I would see him if I turned my head. The feeling was

so strong I was reduced to tears. I had not been thinking of him

before I felt his presence. I had not had this feeling before that

day, neither has it happened since then.'[20]

Experiences of this kind appear to meet all but one of the

normal criteria of hallucination (clairaudience) . For example, Slade and Bentall

proposed the following working definition of a hallucination:(clairaudience) 'Any

percept-like experience which (a) occurs in the absence of an

appropriate stimulus, (b) has the full force or impact of the

corresponding actual (real) perception, and (c) is not amenable to

direct and voluntary control by the experiencer.'[21]

The experience quoted above certainly meets the second and third

of these three criteria. One might add that the 'presence' in such

a case is experienced as located in a definite position in

external physical space. In this respect it may be said to be more

hallucinatory than, for example, some

hypnagogic imagery, (visions) which may be experienced as external to

the subject but located in a mental ‘space’ of its own.[22][23]

Hallucinations (VISIONS) in

bereavement

Rees[24]

conducted a study of 293 widowed people living in a particular

area of mid-Wales. He found that 14% of those interviewed reported

having had a visual hallucination of their deceased spouse, 13.3%

an auditory one and 2.7% a tactile one. These categories

overlapped to some extent as some people reported a hallucinatory

experience in more than one modality. Of interest in light of the

previous heading was the fact that 46.7% of the sample reported

experiencing the presence of the deceased spouse.

Theoretical implications

Psychological

The main importance of hallucinations (visions or

clairaudience) in the sane to

theoretical psychology lies in their relevance to the debate

between the disease model versus the dimensional model of

psychosis. According to the disease model, psychotic states

such as those associated with

schizophrenia and

manic-depression, represent symptoms of an underlying disease

process, which is dichotomous in nature; i.e. a given subject

either does or does not have the disease, just as a person either

does or does not have a physical disease such as tuberculosis.

According to the dimensional model, by contrast, the population at

large is ranged along a normally distributed continuum or

dimension, which has been variously labelled as psychoticism (H.J.Eysenck),

schizotypy (Gordon

Claridge) or psychosis-proneness.[25]

EDITORS NOTE: I

totally disagree with the diagnosis of schzophrenia in that it is

a name given by psychiatrists to experiences they never had

themselves. They drug the hell out of the experiencer, which I do

and do not agree with depending on the severity of the disruption

or fear of the client. If a psychiatrist called in a priest,

minister, nun, or true experiencer for consultation, they might

find that what the client is experiencing is normal and just

doesn't have the awareness that such a thing exists.

Schizophernia truly is a word of the dark ages and should be

sorted out in spiritual terms before drugging such people.

The occurrence of spontaneous hallucinatory (visions or

clairaudience) experiences in

sane persons who are enjoying good physical health at the time,

and who are not drugged or in other unusual physical states of a

transient nature such as extreme fatigue, would appear to provide

support for the dimensional model. The alternative to this view

requires one to posit some hidden or latent disease process, of

which such experiences are a symptom or precursor, an explanation

which would appear to beg the question.

Philosophical

EDITORS NOTE:

The following is clearly written by

someone who has absolutely no spiritual or metaphysical training

whatsoever.

The argument from hallucination has traditionally

been one of those used by proponents of the philosophical theory

of

representationalism as against the theory of

direct realism. Representationalism holds that when perceiving

the world we are not in direct contact with it, as common sense

suggests, but only in direct contact with a representation of the

world in consciousness. That representation may be a more or less

accurate one depending on our circumstances, the state of our

health, and so on. Direct realism, on the other hand, holds that

the common sense or unthinking view of perception is correct, and

that when perceiving the world we should be regarded as in direct

contact with it, unmediated by any representation in

consciousness.

Clearly, during an apparitional experience, for example, the

correspondence between how the subject is perceiving the world and

how the world really is at that moment is distinctly imperfect. At

the same time the experience may present itself to the subject as

indistinguishable from normal perception. McCreery[26]

has argued that such empirical phenomena strengthen the case for

representationalism as against direct realism.

References

- ^

Gurney, E., Myers, F.W.H. and Podmore, F. (1886). Phantasms

of the Living, Vols. I and II. London: Trubner and Co..

- ^

Sidgwick, Eleanor; Johnson, Alice; and others (1894). Report

on the Census of Hallucinations, London: Proceedings of the

Society for Psychical Research, Vol. X.

- ^ See

Slade, P.D. and Bentall, R.P. (1988). Sensory Deception: a

scientific analysis of hallucination. London: Croom Helm,

for a review.

- ^

See, for example, Green, C., and McCreery, C. (1975).

Apparitions. London: Hamish Hamilton, pp. 192-196.

- ^

Ibid., pp. 197-199.

- ^

Ibid., pp. 178-183.

- ^

Irwin, H.J. (1985). Flight of Mind: a psychological study

of the out-of-body experience. Metuchen, New Jersey: The

Scarecrow Press.

- ^

McCreery, C. (2008). Dreams and psychosis: a new look at an

old hypothesis. Psychological Paper No. 2008-1. Oxford:

Oxford Forum.

Online PDF

- ^

Oswald, I. (1962). Sleeping and Waking: Physiology and

Psychology. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- ^ See

Irwin, op.cit., for a review.

- ^

van Eeden, F. (1913). A study of dreams. Proceedings of the

Society for Psychical Research, 26, Part 47, pp. 431-461.

- ^

See Green, C. (1968). Lucid Dreams. London: Hamish

Hamilton, for examples.

- ^

Drever, (1952). A Dictionary of Psychology. London:

Penguin.

- ^

Cf. Green C. and McCreery C. (1994). Lucid Dreaming: the

Paradox of Consciousness During Sleep. London: Routledge.

Chapter 7.

- ^

Bentall R.P. and Slade P.D. (1985). Reliability of a scale

measuring disposition towards hallucination: a brief report.

Personality and Individual Differences, 6, 527 529.

- ^

Green and McCreery, Apparitions, op.cit. p.85.

- ^

Ibid., pp. 85-86.

- ^

Posey, T.B. and Losch, M.E. (1983). Auditory hallucinations of

hearing voices in 375 normal subjects. Imagination,

Cognition and Personality, 3, 99-113.

- ^

James, W. (1890; 1950). Principles of Psychology,

Volume II. New York, Dover Publications, pp. 322-3.

- ^

Green and McCreery, Apparitions, op.cit., p.118.

- ^

Slade and Bentall, op.cit., p.23.

- ^

Leaning, F.E. (1925). An introductory study of hypnagogic

phenomena. Proceedings of the Society for Psychical

Research, 35, 289-409.

- ^

Mavromatis, A. (1987). Hypnagogia: the Unique State of

Consciousness Between Wakefulness and Sleep. London:

Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- ^

Rees, W.D. (1971). The hallucinations of widowhood. British

Medical Journal, 4, 37-41.

- ^

For a discussion of the concept of schizotypy and its

variants, cf. McCreery, C. and Claridge, G. (2002). Healthy

schizotypy: the case of out-of-the-body experiences.

Personality and Individual Differences, 32, 141-154.

- ^

McCreery, C. (2006). "Perception and Hallucination: the Case

for Continuity." Philosophical Paper No. 2006-1.

Oxford: Oxford Forum.

Online PDF

See also

|

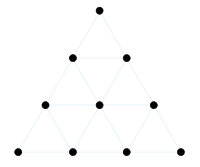

Tetractys

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Tetractys is a

triangular figure consisting of ten points arranged in four

rows: one, two, three, and four points in each row. As a

mystical symbol, it was very important to the followers of the

secret worship of the

Pythagoreans.

Pythagorean symbol

- The Tetractys symbolized the

four elements —

earth,

air,

fire,

and

water.

- The first four numbers also symbolized the

harmony of the spheres and the

Cosmos.[citation

needed]

- The four rows added up to

ten, which was unity of a higher order (in

decimal).

- The Tetractys represented the organization of

space:

- the first row represented zero-dimensions

(a

point)

- the second row represented one-dimension (a

line

of two points)

- the third row represented

two-dimensions (a

plane defined by a

triangle of three points)

- the fourth row represented

three-dimensions (a

tetrahedron defined by four points)

A

prayer of the Pythagoreans shows the importance of the

Tetractys (sometimes called the "Mystic Tetrad"), as the prayer

was addressed to it.

- "Bless us, divine number, thou who generated gods and

men! O holy, holy Tetractys, thou that containest the root and

source of the eternally flowing creation! For the divine number

begins with the profound, pure unity until it comes to the holy

four; then it begets the mother of all, the all-comprising,

all-bounding, the first-born, the never-swerving, the

never-tiring holy ten, the keyholder of all".[citation

needed]

As a portion of the secret religion, initiates were required

to swear a secret oath by the Tetractys. They then served as

novices for a period of silence lasting three years.[citation

needed]

The Pythagorean oath also mentioned the Tetractys:

- "By that pure, holy, four lettered name on high,

- nature's eternal fountain and supply,

- the parent of all souls that living be,

- by him, with faith find oath, I swear to thee."

The Pythagorean SourceBook claimed that there were 2

quaternaries of numbers, one which is made by addition, the other

by multiplication; and these quaternaries encompass the

musical,

geometric and

arithmetic ratios of which the harmony of the universe so

composed. The first quartenary is 1,2,3,4. There are 11 total

quartenaries. And the perfect world which results from these

quaternaries is geometrically, harmonically and arithmetically

arranged."

It is said that the Pythagorean musical system was based on

the Tetractys as the rows can be read as the ratios of

4:3,

3:2,

2:1, forming the basic intervals of the Pythagorean scales.

Pythagorean scales are based on pure fifths (in a 3:2 relation),

and pure fourths (in a 4:3 relation) which form a stable optimally

blending intervals. The ratios of

1:1

and 2:1 generate stable purely blending intervals. Note that the

disdiapason, 4:1 and the diapason plus diapente, 3:1, are

consonant intervals according to the tetractys of the decad, but

that the diapason plus diatessaron or perfect 11th, 8:3, is not.

Quote:

- "The Tetractys [also known as the decad] is an

equilateral triangle formed from the sequence of the first

ten numbers aligned in four rows. It is both a

mathematical idea and a

metaphysical symbol that embraces within itself — in

seedlike form — the principles of the natural world, the

harmony of the cosmos, the ascent to the divine, and the

mysteries of the divine realm. So revered was this ancient

symbol that it inspired ancient philosophers to swear by the

name of the one who brought this gift to humanity —

Pythagoras."

Kabbalist symbol

Symbol by early 17th-century Christian mystic

Jakob Böhme, including a tetractys of flaming Hebrew

letters of the Tetragrammaton.

There are some who believe that the tetractys and its

mysteries influenced the early

kabbalists. A Hebrew Tetractys in a similar way has the

letters of the

Tetragrammaton (the four lettered name of God in Hebrew

scripture) inscribed on the ten positions of the tetractys, from

right to left. It has been argued that the Kabbalistic

Tree of Life, with its ten spheres of emanation, is in some

way connected to the tetractys, but its form is not that of a

triangle.

Tarot card reading arrangement

In a

Tarot reading, the various positions of the tetractys provide

a representation for forecasting future events by signifying

according to various occult disciplines, such as Alchemy.

[1] Below is only a single variation for interpretation.

The first row of a single position represents the Premise of

the reading, forming a foundation for understanding all the other

cards.

The second row of two positions represents the cosmos and

the individual and their relationship.

- The Light Card to the right represents the influence of

the cosmos leading the individual to an action.

- The Dark Card to the left represents the reaction of the

cosmos to the actions of the individual.

The third row of three positions represents three kinds of

decisions an individual must make.

- The Creator Card is rightmost, representing new decisions

and directions that may be made.

- The Sustainer Card is in the middle, representing

decisions to keep balance, and things that should not change.

- The Destroyer Card is leftmost, representing old

decisions and directions that should not be continued.

The fourth row of four positions represents the four Greek

elements.

- The Fire card is rightmost, representing dynamic creative

force, ambitions, and personal

will.

- The Air card is to the right middle, representing the

mind,

thoughts, and strategies toward goals.

- The Water card is to the left middle, representing the

emotions, feelings, and whims.

- The Earth card is leftmost, representing physical

realities of day to day living.

Other symbols

See also

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

PYTHAGORAS DATABASE

TAROT DATABASE

TETRAGRAMMATON DATABASE

KABBALAH DATABASE

VISIONS DATABASE

CHRIST DATABASE

MOTHER MARY DATABASE

SALVATION DATABASE

BIBLE DATABASE

GOD DATABASE

TRIANGLE DATABASE

ALCHEMY DATABASE

COSMOLOGY DATABASE

CREATION DATABASE

FREE WILL DATABASE

DREAMS OF THE GREAT

EARTHCHANGES - MAIN INDEX

|